I have experienced some loss over the years, none more difficult and painful than in 2019, when I lost my mum to pancreatic cancer. The pain was indescribable, like nothing I’ve ever experienced. In the weeks and months that followed, I had to adjust to the fact that overnight, my life had immeasurably changed. I now had to adapt to a totally new way of life – one which felt uncomfortable, unfair, and at times pointless.

During these times, I was reminded of the grief people experience after receiving a life-changing diagnosis, like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Naturally, this type of grief is somewhat different to the grief experienced when a loved one dies, but it is still a form of grief. You are grieving the loss of your pre-diagnosis life... and it’s an important, and necessary process which you must go through.

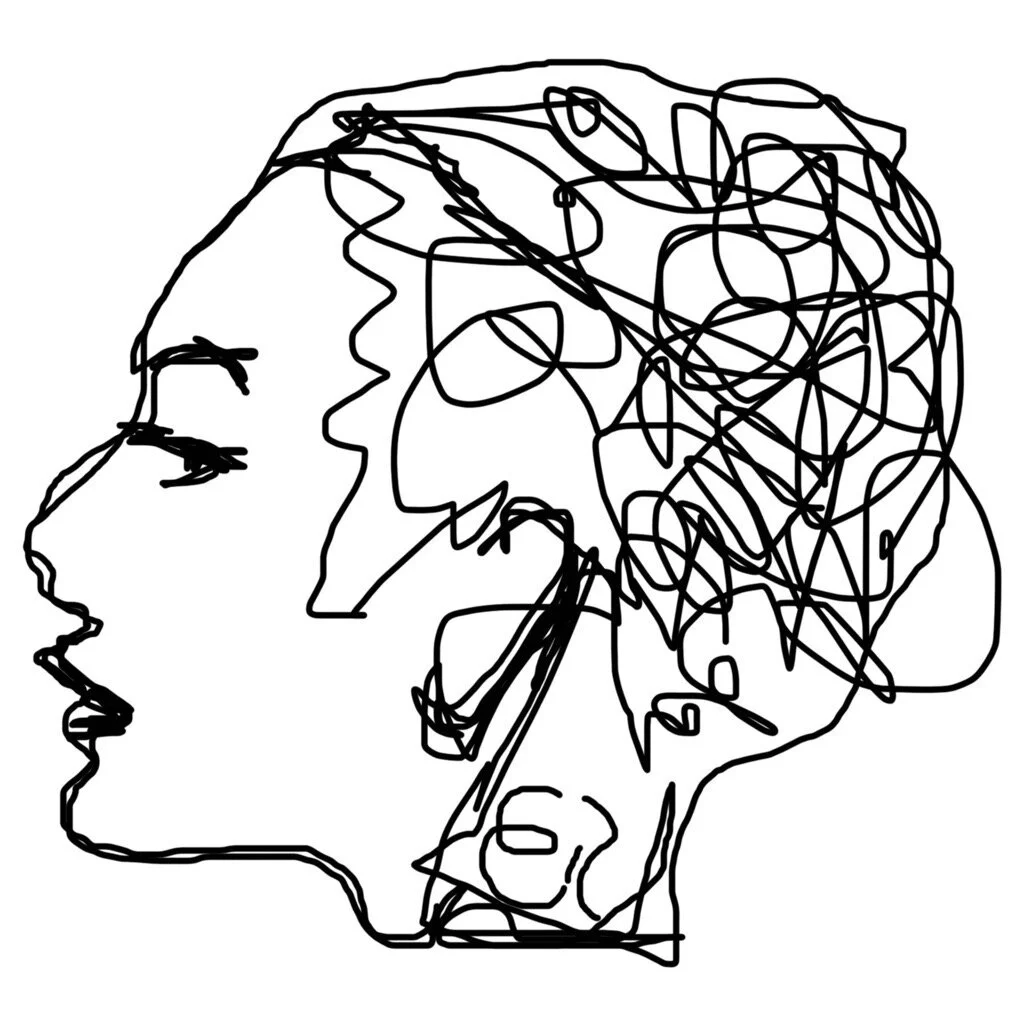

Grief strikes each person differently. After all, we all have our own, unique ways of dealing with challenges and heartache in life. A friend recently sent me a surprisingly accurate analogy of grief, which hit the nail on the head. It shows that for most people, grief of a loss, whatever that loss may be, never leaves a person completely. The loss never goes away, but it may change over time.

Imagine your life as a box. Inside the box, there is a ball, which is the grief you feel, as well as button which when pressed, causes pain. During the early days after your loss, everything is new. Everything is raw. The ball of grief is overwhelming, and so large, that every time you move the box... that is, every time you try to move through your life, the ball of grief cannot help but hit the pain button – constantly. This represents that initial experience of loss – when you can’t control or stop the pain that you are feeling. It is just relentless, no matter how much others try to support and comfort you. At this point in time, it feels as though the pain is unrelenting, and will be like this for the rest of your days.

However, over time, the ball starts to shrink on its own. As you go through your life, and as the box moves, the ball still rattles around inside the box. However, because the ball is now smaller, it hits the pain button less often. In one sense, you may feel that you can go through most days without having the pain button hit. However, when the ball does hit the pain button, it can be completely unexpected – and hurts just as much as it did during the early days of your loss. This could happen when you’re in a particular place, such as at the hospital, or when listening to a piece of music that reminds you of your life before your diagnosis. It could be anything that is personally meaningful to you.

As time passes, the continues to shrink and with it, so does the grief for the loss we have experienced. However, we never forget the loss that we have experienced. We must acknowledge that there will be days when the ball does hit that pain button, and when it does, we must be kind to ourselves.

“We must accept sadness as an appropriate, natural stage of loss.”

Upon reflection, it’s quite easy to see how this analogy somewhat resembles the process we go through after loss. I’ve certainly seen it after the loss of my mum, but also thinking back to when I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. I’ve also observed this with other people I’ve met along the way living with a variety of chronic health conditions. However, the process isn’t straight-forward – nor something we can plan for. It’s personal for each and every one of us.

In 1969, Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross introduced the five stages of grief model. The model describes how people experiencing grief go through a series of five different emotions: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. While the model has received criticisms, Kübler-Ross said that she regarded these stages as reflections of how people cope with illness and dying, rather than reflections of how people experience grief. What is certain is that these stages are not linear and predictable.

Let’s start with denial. Can you remember the thoughts that went through your head when you received your diagnosis? Denial is an entirely normal reaction to rationalise those overwhelming emotions that we experience. You can almost regard denial as your human defence mechanism to when you receive that shocking news, and when you begin to think about what you have lost.

Then there’s anger, which often consumes our souls once the denial starts to diminish. As the pain of the realisation sets in, and as your senses begin to heighten to your surroundings, those feelings of intense frustration and grievance set in, as we start to search for blame. For some, the anger may build up internally, whereas for others, their response mechanism may to be to lash out at everyone and everything around them.

Along comes bargaining at some point. You know, the stage where you think, ‘What if...’ This serves a really important purpose – and often a temporary escape from the pain you’ve been experiencing. For there may just me small, tiny glimmers of hope, amidst the chaos and despair.

There’s also depression. In the past, I’ve sometimes felt scared of the term – or rather, the label that can exist in society. But what’s unnatural about depression in these circumstances? It is an entirely rationale and appropriate response as you deal with a great loss. From the intense sadness, to the overwhelming lack of motivation, poor sleep and altered appetite – it’s all part and parcel of dealing with something as colossal as life-changing diagnosis. Again, the experience of depression will vary between every individual, and indeed within yourself, depending on ‘where’ you are at any given moment in time.

Finally, there’s acceptance, although it’s certainly not ‘final’. Here, you succumb to the reality of your loss, and understand that no matter what you do, nothing can change that reality. This doesn’t mean that you are ‘okay’ or ‘happy’ with the loss that you have experienced; however, it does mean that you are getting your head around it, and are learning to live your life, albeit different, in the best way possible.

I have no doubt that so many people living with IBD can relate to these different stages and emotions – which can often feel like one big mess, sometimes happening concurrently, and most certainly in a disordered, confusing way. There will always be days when you think, ‘I’ve had enough of this’ – I know I still have those, but they are less frequent as time goes by, and as I learn to adjust to present life. It’s a bit like being out at sea. Sometimes, the sea feels calm, and you can see the beauty in the world. At other times, the waves overwhelm us. When you feel like this, just remember to swim and look for dry land. It’s all we can really do.