NEWS

Re-discovering Myself

by Aiswarya Asokan (South India)

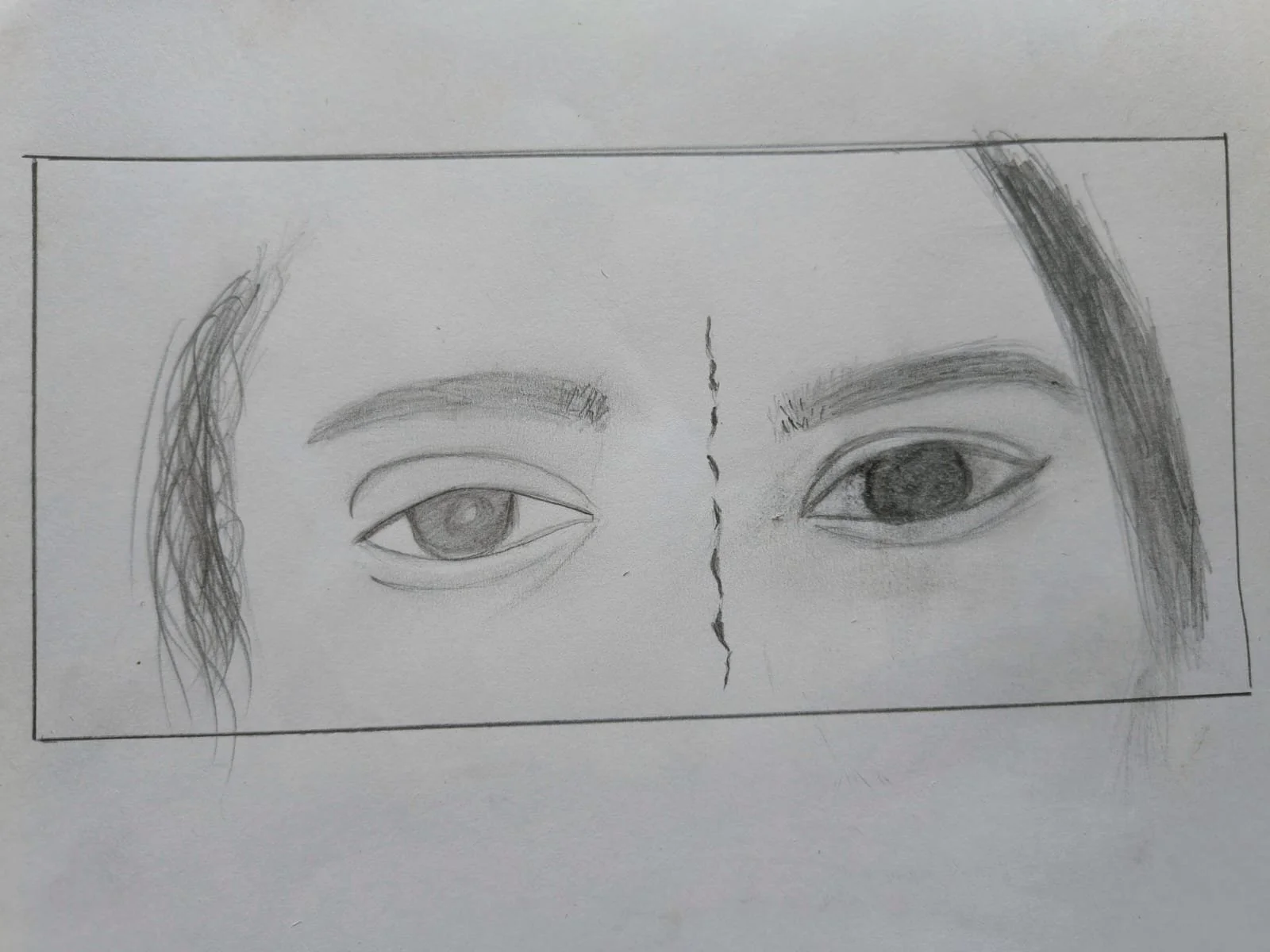

About the artwork:

The eye on the left hand represents depression, pain, withdrawal and hopelessness, while the one on the right-hand side represents fire, aggression, hunger, frustration, control and the drive for action. The broken line in the middle represents a surgical scar, which remains a symbol of the cost paid by the body for balancing the clash of emotions. The body as a whole is trying hard to hold it all together, to find the balance for emotional stability, for safety, for peace, for happiness. It is looking out for compassion, it is looking for love. And the only way to get to know what it is looking for is to look inward.

Some Things You Learn to Accept Without Questions

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Sometimes there are things in life you learn to accept without asking why. For me, asking questions only made the stress worse, and stress only made my illness harder to survive.

I was diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when I was very young. Looking back now, I can see how different I was from other children. I was always tired, weak, and running out of energy. While others played and dreamed freely, my body felt heavy, as if it was always asking me to slow down.

School was especially hard. Learning took more effort than I could explain, and there were moments when my body completely failed me. I remember fainting during exams—lying there while the world blurred around me, carrying not only pain but deep embarrassment. Being different from your classmates hurts in ways words can’t easily describe. It makes you feel invisible and exposed at the same time.

There were many days I cried alone. Not being able to do what you want as a child slowly takes away your hope. I watched my classmates move forward while I felt stuck, left behind by a body I didn’t understand. I began to believe that maybe I would never become “someone.”

IBD didn’t just affect me—it affected my family too. I saw their worry, their sacrifices, and their quiet strength. Watching the people you love struggle because of your illness leaves a mark on your heart that never fully fades.

For a long time, I didn’t have the words to explain what I was going through. When people said, “I have no words,” I never understood it. Now I do. My own words were scared. They hid behind silence, afraid to come out.

IBD delayed my education, interrupted my plans, and shook my confidence. But it did not destroy me.

What I have learned is that resilience grows quietly. Hope doesn’t always arrive loudly—it sometimes appears in the simple act of waking up and trying again. Even when the path feels unbearable, even when progress is slow, survival itself becomes an act of courage.

Yes, I am later than others.

But I am not behind.

I am surviving something incredibly hard, and I am still standing.

Today, I am a woman with a past shaped by pain, a heart filled with empathy, and a future that has not been canceled. My journey may look different, but it still matters. And if my story can help someone feel less alone, then every difficult step has meaning.

Featured image from Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash.

Reflections on AIBD 2025

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

In early December, I had the privilege of attending the Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (AIBD) conference in Orlando, Florida. While trying to describe my experience, the words that keep coming to mind are “life-affirming.” I couldn't be more grateful to be in a space surrounded by doctors who were passionate about IBD treatment and driven to learn the newest research in the field.

My entire experience with CCYAN has made me rethink my experiences as a patient and what I need from my doctors. The thing I seemed to be missing most was the WHY behind their decisions and treatment recommendations. I know appointments are brief, but knowing the reasoning behind the drugs prescribed or questions asked would have made me trust a few of my previous gastroenterologists a little more. As someone diagnosed with Microscopic Colitis (MC) who was on steroids for years, it was incredibly validating to hear the experts at AIBD acknowledge that steroids are dangerous and should only be a short term solution as a bridge to another treatment. They also recommended steroid use sparingly and tapering whenever possible. It was also interesting to learn about which drugs are first or second line drugs in the treatment of IBD. Sometimes, it can feel like doctors just throw drugs at us waiting for the right one to stick. I liked being able to see that there was a set plan and procedure for treatment options in place.

A refreshing update the conference covered was their take on anxiety and depression. They said that all gastroenterologists should be asking their patients if they're experiencing anxiety or depression. I learned that having one or both of these can affect medication compliance and drug effectiveness. The conference speakers pushed the importance of prehabilitation - preparing the patient pre-op to optimize outcomes. Prehabilitation does more than just help surgical outcomes, according to studies done by Dr. Gil Melmed, it can save hospitals thousands of dollars in the long run. Another important note mentioned early on at AIBD was that vaping and e-cigarette use are a significant risk factor for post-operative recurrence and poorer overall outcomes. Doctors also acknowledged that although IBD patients sometimes say they are doing “well," it may not necessarily mean “well" by normal standards. It can mean a lot of things such as infrequent bouts of symptoms, symptoms that don't interfere much with their daily life, or symptoms that vary or subside after a while. By digging deeper and having open discussions with their patients, doctors can gather more helpful information and set their patients up with the necessary resources.

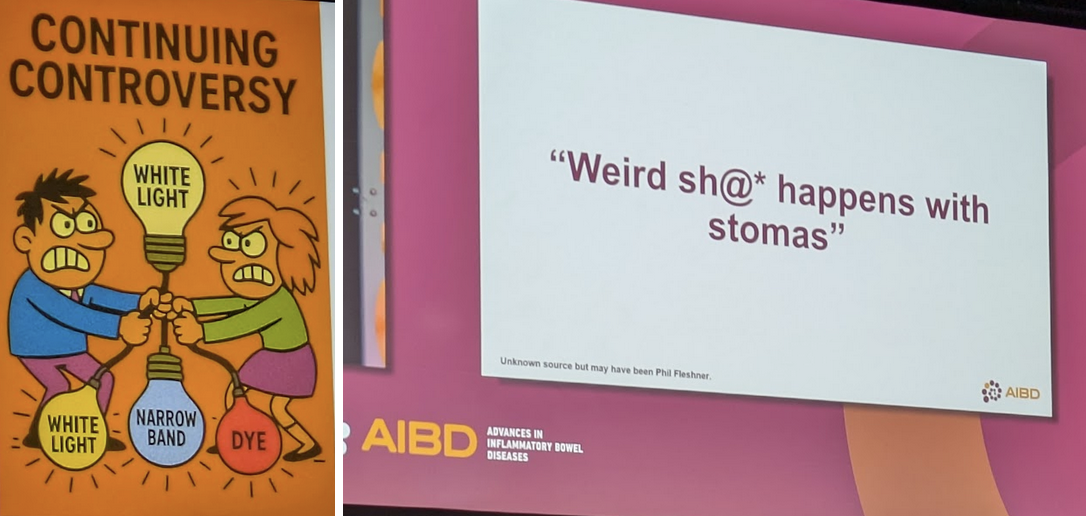

I also loved seeing the doctors’ personalities come out at the conference. From showing powerpoints reading “weird sh@* happens with stomas” to hearing surgeons argue over their preferred method of stitching up a pouch, it was refreshing to see their passion and silliness. Some speakers’ PowerPoints were more serious with surgical photos and case studies while others used fun slogans and humorous cartoon graphics to get their points across.

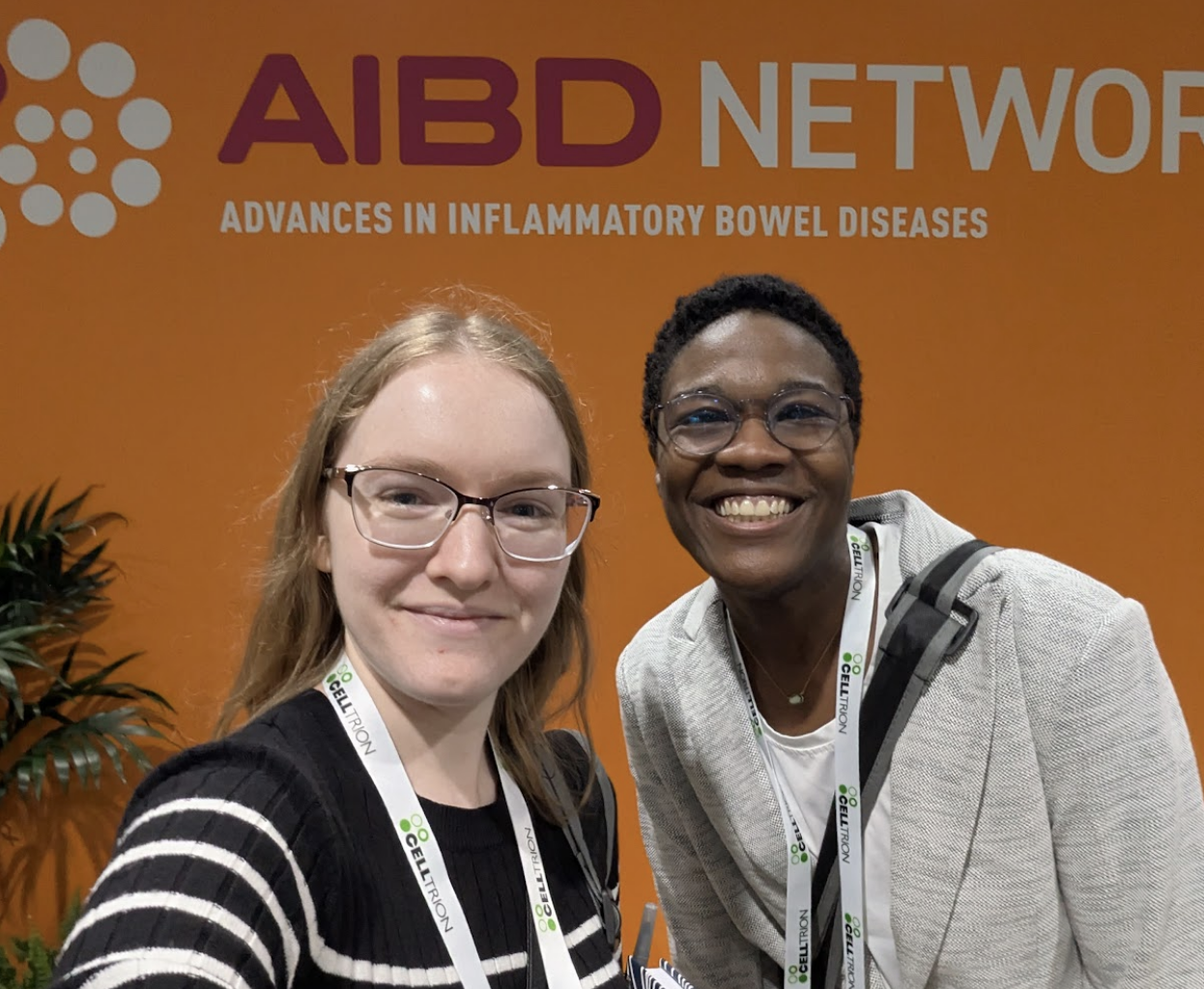

On a personal level, this was my first experience traveling independently across the country. I flew to Florida, navigated the airports, took Ubers, and even took a solo trip to Disney for a day. Despite a few hiccups along the way, (I’M LOOKING AT YOU BROKEN TOILET PIPE), this trip gave me an immense sense of accomplishment and confidence that I can figure things out for myself. I'm hoping to take my newfound independence to new heights in 2026 and go on many more solo adventures. I'm so glad I got the chance to meet Lexi, another CCYAN 2025 fellow, who has such a positive and lighthearted presence. I love how she takes everything in stride and I hope to have her boundless energy one day. I also met CCYAN alumni Mara and Grady (and of course Mara’s service dog Rooster) as well as CCYAN founder Sneha. They were the best group I could have asked for and they were so supportive when I flared during the last day of the trip.

I can also definitively say that there will be more medical conferences in my future. I’m not exaggerating when I say AIBD was more fun for me than Disneyworld. Getting the chance to attend any and all lectures I wanted was a dream come true! I went to every surgical track lecture, just for the fun of it. I took pages upon pages of notes and came up with a very hefty list of vocabulary words to research for next time. Being at the medical lectures just felt so right. As a teacher, one of my top goals is to develop every child into a lifelong learner - someone who stays inquisitive and follows their passion long after they receive their diploma. I hope I have successfully modeled that for my students and continue to do so. It was amazing to be in a room of a thousand lifelong learners who all want to hone their practice and be better-informed when treating their IBD patients.

Thank you again to CCYAN for this amazing opportunity and for connecting us all into one big IBD family. I'm forever grateful. As they say in Hamilton, “I wanna be in the room where it happens...I've GOT to be in the room where it happens”. Until next time…

Farewell 2025 — A Journey of Self-Discovery, Resilience, and Growth

by Rifa Tusnia Mona (Dhaka, Bangladesh)

I can’t believe 2026 is already here! There are so many things that feel surreal to me actually. After having crohn’s, I was bedridden for a long time. While looking at the white plastered roof upside, I knew I was stuck in my life. I didn’t have a terminal illness which meant I wasn’t dying! But, with frequent flare-ups, cramps, weight-loss, and hospitalization reminded me that normal life wasn’t possible either. At some point, I felt blank inside. I remember when someone would ask what I am planning to do with my future, I would say, close your eyes and you will see! They would say it’s pitch black when I close my eyes! Then I would hilariously say, Correct! That’s my future! And that would’ve been true until I decided to finally get up and go all-out. I often say to my mom, ‘Ammu, even if there was an ounce less pain, I wouldn’t have gotten where I am now!’ I felt graceful to god as the pains were coming from all directions and at some point they became the reason for my living.

In the past few months, I boarded a plane six times, traveled to India twice from Bangladesh, and moved to a different continent! To Europe, in Lisbon, far away from the comfort zone of my room, my bed!

I have very small veins, and my body does not absorb oral medications effectively, which made the intravenous treatment particularly challenging. There were days when cannulation was urgently required, yet despite repeated attempts throughout the day, the nurses were unable to locate a suitable vein. By the end of those days, my hands were so exhausted and numb that I could barely feel them anymore.

By this time, the hospital feels like a second home! I got married to Crohn’s and the hospital became my in-laws! Funny, right!

Despite everything, I remain grateful. I am currently at the closing stage of my first semester of my Master’s program in Lisbon, and as part of the mobility track of the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master’s program, I will be moving to the Netherlands in February. The travel plan is almost ready and I am confident that I can do it.

Living with Crohn’s disease has reshaped my sense of fear. When survival itself becomes the central challenge, traditional definitions of success begin to fade. That is what happened to me. Compared to where I once stood, I am no longer simply enduring life; I am moving forward with purpose. That, above all, is what matters to me.

I’ll keep this brief, as I’m currently admitted to H.S.A. Capuchos Hospital, Lisbon, due to a recent flare-up. I’m not sure if my words will inspire, but if even one person feels a little encouraged after reading my story, it will mean the world to me. I am deeply grateful to CCYAN for giving me a platform to share my story, my voice, and my true feelings. I hope the new year brings a fresh start for everyone, filled with love and happiness. Thank you for reading!

Featured photo: A photo of me in front of the university gate taken by my beautiful friend, Hiba Hamada.

The Vasovagal Response and IBD

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

As someone with several medical phobias, I have always been a fainter. Being in a heightened state of fear and stress is a recipe for disaster that usually leads to me being on the ground. It takes skill to faint and take out a row of chairs and your mother at the doctor’s office, but I like to think that I’m improving with time and therapy (see my phobias article for details). However, when I began having digestive issues in college, I started experiencing pre-syncope symptoms frequently during flareups that have lasted to this day. Doctors always told me it was a vasovagal response, so I have been asking nurses and reading up on research in the hopes of finding some answers. Though I have not figured out how to completely stop my symptoms, here is what I have found on the subject and some strategies that may help.

IBD can come with a multitude of strange and hard-to-explain symptoms with some occurring outside of the gastrointestinal system. These extraintestinal manifestations can include feeling faint during a period of intense stomach pain or dizzy during a bowel movement. The vagus nerve and parasympathetic nervous system connect the gut, heart and brain, causing a plethora of vasovagal symptoms when thrown out of balance.

For some background information, syncope is a medical term for fainting while presyncope describes the symptoms one experiences when they almost pass out - including dizziness, nausea, blurry vision, weakness, and chills or sweating. Both syncope and presyncope can be signs of different conditions, but are also strongly attributed to vasovagal syncope. Vasovagal syncope is experienced by around a third of the world and is a common symptom of dehydration, giving blood, standing up too quickly, etc. (Johns Hopkins Medicine, Syncope). According to Verywell Health, a vasovagal response can have physical triggers, such as straining during bowel movements, stomach illness, and pain, or emotional triggers like anxiety, trauma, fear, or stress (Bolen, 2025).

**It’s important that if you experience syncope or pre-syncope symptoms that you get checked out by a doctor. Tests like an Electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, tilt table test, CT, MRI, carotid artery ultrasound, and more can be used to rule out serious heart problems, seizures, or conditions like POTS.** (Johns Hopkins Medicine, Syncope)

According to the paper “The autonomic nervous system and inflammatory bowel disease,” there is strong evidence supporting the connection and interaction between the central nervous system and the intestines. When the body is triggered by high stress or chronic stress, it can have a direct effect on our gut’s inflammatory response. Vagal neurons permeate the gut wall and play an important role in the transfer of information from the gut to the central nervous system and vice versa. This connection is commonly known as the gut-brain axis. These sensitive nerve connections can even affect our perception of IBD-associated pain and disease symptoms can be exacerbated (Taylor & Keely, 2007). Our bodies need to find a balance between the nervous system and gut. Too much or too little activation can trigger responses in multiple areas of the body and have unforeseen consequences.

Some common vasovagal response symptoms are:

Tunnel vision/blurred vision

Dizziness

Weakness

Ringing in the ears

Cold or clammy skin

Feeling hot

Nausea

A temporary drop in blood pressure (Bolen, 2025)

Syncope or fainting

Short term amnesia or confusion upon waking

Brief convulsions of the limbs (Wang et al., 2024)

What can you do during a vasovagal episode?

Sit or lie down (injury prevention)

Put your head between your knees

Avoid straining

Stay hydrated

On top of those tips, this is how I deal with repeat vasovagal episodes:

Firstly, I document everything so I can give my doctor a better idea of what I experience and how frequently. A smart watch is also useful so I can keep track of my bpm. There are a few trusted friends and family members that know of my condition and the warning signs. Of course, it’s helpful if you know your own body’s warning signs - it can help you predict it before it happens.

I also keep my phone on me at all times in case I need to call for help. After a vasovagal episode, I give myself time to feel better - usually curling up on the couch with a blanket and some water. I always use electrolytes to help my body recover faster and I keep heating pads with me since I can feel cold or shaky afterwards.

Possible forms of treatment that I’ve learned about:

Medication

Physical counterpressure maneuvers (Wang et al., 2024)

Pelvic Floor Therapy

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Psychotherapy

I found it interesting that one medical professional recommended looking into psychotherapy to address the psychosocial component of vasovagal responses. Having fainting episodes or those revolving around intense pain can be terrifying and that fear can stick around long after the incident ends. Traumatic memories of pain around bowel movements can cause increased anxiety and escalate vasovagal responses. Confronting your anxiety and the reasons behind your fight/flight/freeze can help mitigate symptoms. By always having a plan and knowing the signs, I can better prepare myself to deal with vasovagal responses.

Works Cited:

Bolen, B. (2025, October 30). Common causes and triggers of the vagal response. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/vasovagal-reflex-1945072

Syncope (fainting) | Johns Hopkins Medicine. Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/syncope-fainting

Taylor, C. T., & Keely, S. J. (2007). The autonomic nervous system and inflammatory bowel disease. Autonomic Neuroscience, 133(1), 104–114.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2006.11.005

Vagus nerve: What it is, function, Location & Conditions. Cleveland Clinic. (2022, November 1). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22279-vagus-nerve

Wang, J., Li, H., Huang, X., Hu, H., Lian, B., Zhang, D., Wu, J., & Cao, L. (2024, April 10). Adult vasovagal syncope with abdominal pain diagnosed by head-up tilt combined with transcranial Doppler: A preliminary study. BMC neurology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11005138/#:~:text=The%20value%20of%20HUT%20combined,the%20adoption%20of%20safety%20measures

Featured image from Henrik Dønnestad on Unsplash.

Shaping the Blank Pages of Us: IBD & Society

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

There must be a life catalyst in every person’s journey, something that stirs us, shapes us, and pushes us forward. For many people living with chronic illnesses like Inflammatory Bowel Disease, that catalyst is not only the condition itself but also the society around them.

Whether we recognize it or not, society plays a deep and lasting role in how IBD patients see the world and how they see themselves. From our earliest days, we learn what people consider “normal,” what is acceptable to talk about, and what should be hidden. For someone with IBD—a disease that is often invisible, stigmatized, and misunderstood—society’s voice can either be healing or deeply hurtful.

IBD teaches us that education doesn’t only begin in the classroom; it begins in the spaces between people. It starts in whether communities choose empathy over judgment when someone struggles with pain, fatigue, or multiple hospital visits. It begins with whether people understand that “You don’t look sick” is not kindness—and that invisible illnesses are real and heavy.

Every person is born as a white page—blank, pure, ready to be written with experiences, lessons, and love. But for someone with IBD, society often writes the first words: misunderstanding, stigma, or silence. That is why it matters so deeply what kind of world we create around chronic illness. A supportive, kind, and educated environment can be the difference between a patient who suffers in silence and one who lives with dignity, confidence, and hope.

Being a good person costs nothing. We lose nothing by choosing kindness toward those living with IBD. A little understanding when someone cancels plans, a bit of patience when they are too tired to continue, or simple respect for their medical journey—these things truly matter. They lighten the emotional burden that is often heavier than the disease itself.

If only society remembered that. If goodness and awareness came as naturally as breathing, people with IBD wouldn’t have to hide their pain or feel ashamed of their scars, surgeries, or symptoms. A smile, a word of encouragement, a willingness to learn, these small acts can be a lifeline for someone navigating an illness that affects every part of their life.

Let us be the catalyst. Let us be the people who make IBD visible, who break the silence, who show that being human means supporting one another beyond our comfort zones. It means listening to the stories of IBD warriors, respecting their challenges, and standing beside them in their fight.

In the end, it’s not wealth or fame that defines a society—it’s how we treat the most vulnerable. May we choose to be a society that uplifts those living with IBD, a society that listens, understands, and helps shape lives not through judgment but through compassion. Because when society chooses kindness, an IBD warrior’s blank page becomes a story of courage—and that changes everything.

Photo credit goes to: https://stockcake.com/i/sunset-in-hand_1221433_547021

HealtheVoices 2025: Feeling Beautifully at Home with my IBD

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

Disclaimer from Michelle: Johnson & Johnson paid for my travel expenses to attend HealtheVoices, but all thoughts and opinions expressed here are my own. This conference was not attended as a part of the CCYAN fellowship.

From November 6th through November 9th, 2025, I stepped into a space that I had never experienced before. HealtheVoices 2025 was more than a conference for advocates like me. HealtheVoices became a place where my body, story, and heart finally felt understood. I walked in as an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and mental health advocate, but I walked out feeling like I had reclaimed parts of myself that IBD had slowly worn down.

IBD affects so much more than the digestive system. My life is shaped by symptoms that are unpredictable and exhausting, with my mental health experiences running parallel to this journey and adding additional weight. IBD ultimately shapes the way that I move through the world, my energy, my confidence, and even the level of honesty that I bring to conversations. Daily life can feel even more heavy and lonely because it is rare for me to be in a room filled with people who truly understand what chronic illness feels like, and vulnerability about illness does not always land well with people who cannot relate. At HealtheVoices, that weight softened the very moment that I arrived. The environment made me feel safe before I even realized that I had been holding my breath for so long.

I met people living with many types of chronic conditions, from visible disabilities to more silent illnesses like mine. I met caregivers who understood illness from the position of love and exhaustion. I met people who shared my diagnosis of IBD and people who shared my mental health struggles as well. In turn, I finally did not feel like the odd one out or like the only person in the room fighting a battle that no one else could see. For one weekend, I felt truly seen, understood, and supported. It felt like everyone there spoke a language that I always knew but rarely had spoken back to me. It was a rare and profound reminder that community, safety, and understanding can change the way a chronically ill body feels because, to put it simply, I finally felt normal.

While I cannot speak for all of the attendees, I know that I felt this way for a variety of reasons, and I am going to try my best to put it into words.

For starters, I could tell that the conference itself was intentionally designed with us in mind, and that intention showed in every detail. Organizers checked-in on us often, encouraged rest, and made it clear that nothing was mandatory. They understood that rest is both a need and a responsibility. They understood that pushing too hard could cause flare ups, particularly for those of us with IBD or conditions that involve fatigue, pain, and unpredictable symptoms. Even travel was supported as I received reminders and check-ins to make sure that I made it to my flight safely. This took the emotional labor out of the small things that usually drain me, and their help and accommodations were never made to feel like favors. Plus, everything was optional, yet everything was thoughtfully provided. It was all offered with genuine care, and that is something that I rarely feel in spaces outside the chronic illness community. I truly felt taken care of at every moment. I never felt pressured to show up to an event, and I never felt like a burden or a "waste of an attendee" if I did not. I felt valued simply because of who I am, IBD and all. Typically, I am made to feel as though my IBD devalues me throughout many domains of life, but I felt the opposite way while at HealtheVoices. I also felt considered and looked out for without being pitied or restricted. In other words, I felt empowered to take care of myself and to be the advocate I want to be, while also realizing that there is power in accepting help and care—there is the "power of us."

Regarding this "power of us," I was able to witness and experience how chronic illness can foster unity, even when diagnoses and symptoms may differ. This was exhibited right off-the-bat at the very first dinner of the conference when attendees were grouped based on their health condition, and I accidentally sat with the mental health and pulmonary hypertension group instead of the immunology group. What started as an awkward mistake due to my brain fog after a long day of traveling ended up turning into a gift. At this dinner, I connected with people who understood my mental health story in ways that felt grounding and familiar. Some even worked in the mental health field like I do, which felt incredibly validating. Therefore, even though not a single individual there had IBD, our emotional landscapes were still strikingly similar. We each shared our stories of career challenges, burnout, medical dismissal, discrimination, chronic pain, hospital admissions, fatigue, chosen family, the exhaustion of being misunderstood, and the emotional toll of navigating life and relationships with an unpredictable body and/or mind. We also connected over experiences specific to gender, such as being dismissed in medical settings until a male caregiver shows up.

These discussions reminded me that chronic illness is not defined only by biology. It is shaped by stigma, gender, identity, socioeconomic realities, and the emotional toll of constantly having to justify our experiences. Even people whose conditions had nothing in common with mine understood the same nuances of fatigue, pain, fear, and perseverance. Our hearts carried extremely similar stories, and the overlap was both comforting and heart-wrenching at the same time.

After that realization, I made a conscious effort for the rest of the weekend to approach people without looking at their badges. I did not want to lead with diagnoses anymore since I understood that a diagnosis was not the only thing that could foster deep connections. I wanted to understand people for who they were rather than for what condition they advocated for, even though I understood that advocacy often played a large role in the attendees' identities.

Despite it being an advocacy conference, my goal was not to advocate or educate that weekend. I simply wanted honest connection. I wanted to feel safe being myself. I wanted to meet people who would understand both the heaviness and the humor that come with living in a body that needs extra care and requires constant negotiation, without limiting myself by my diagnosis. My IBD has limited me enough already, and I was not going to let it stop me from making the meaningful connections that I have been seeking just because of a label. As it is, living with IBD and mental health challenges is incredibly isolating, especially when daily experiences and honesty are treated as oversharing. Everyone, including myself, preaches vulnerability, but it is difficult to be vulnerable when people do not know how to respond or cannot relate to your daily reality. That is why having the space to openly share about your day-to-day life—without the sugarcoating—is essential, and I found that space with each and every attendee carrying all of the diagnoses under the sun. It did not matter if they had IBD, a different chronic illness, or if they were a caregiver since we could all relate to one another in some way.

This was an incredible phenomenon that attendees and I noticed since at HealtheVoices, we did not have to explain the basics. Each conversation started with an innate understanding of one another. This understanding was not just based in compassion and shared experiences as it was oftentimes also based in shared medical knowledge/terminology, tips and tricks for navigating the healthcare system, etc. This is because everyone there lived some version of the same complexity. For example, many of the attendees understood Prednisone's mental and emotional side effects, sometimes even making light of it nonchalantly during conversations. Outside of the chronic illness space, these jokes and statements would have to be explained or given some background information, which can become exhausting over time, especially as you meet more people throughout your life. Having people who just "get" certain things—without needing to pause the conversation to explain and without having to worry about how it might be taken—is a breath of fresh air.

I did not have to soften the truth or worry about being labeled as "dramatic" or "negative." I did not have to explain why I left an event early or arrived late, nor did I have to explain why I did not finish the food on my plate. People just got it. This conference felt like a safe haven where I did not have to justify my needs or my existence as someone living with IBD. Even when we were not familiar with aspects of each other's health condition(s), we approached one another with curiosity rather than making assumptions, offering unsolicited medical advice or "natural remedies" that we have likely already tried/been advised to try countless times, or making remarks along the lines of, "everything happens for a reason" and "at least it's not cancer."

Conversations were honest but never forced, and I found that our weekend did not revolve entirely around illness. Sure, we cried a lot, but we also laughed a lot. We talked about hobbies, goals, spirituality, tarot, and things that were not centered in our diagnoses. It felt balanced in a way that my everyday life rarely does since either my whole world feels tied to my IBD, or I attempt to live in denial of its existence. At HealtheVoices, I did not have to shrink or edit my truth.

Yet, there was a moment very early into the weekend when I felt myself growing emotionally tired. While there were those intriguing conversations outside of chronic illness, most conversations were still deep and personal in nature. As a result, I felt an unexpected countertransference building inside of me, as if I had automatically tried to become the "listener" and "helper." Hearing such heavy stories that mirrored my own felt draining at first because I empathized deeply, and I wanted to hold people's burdens for them for as long as I could. That is what I am used to doing for others, and that is what I honestly enjoy doing. I see it as a privilege to be trusted with such personal information and stories of deep pain. Thus, I wanted to show my gratitude for this privilege, which expressed itself as me unconsciously attempting to relieve some of their burdens. It was as if I had naturally tried to step into the role of "therapist" instead of simply being myself. It is a habit that comes naturally to me, especially since I am entering the mental health field as a therapist and hope to work with people who have chronic illnesses.

I also initially experienced some imposter syndrome early into the conference. I was surrounded by these incredible advocates, many of whom have been advocating for decades. Some were even making a career out of their advocacy journeys. Even though it feels like IBD has been a part of my identity for my whole life, I was only diagnosed 4.5 years ago. Similarly, even though I feel as though I have been advocating for years, I really have only been actively advocating and becoming involved in the IBD community this past year. This made me begin to question why I was selected to attend the conference. What the heck do I have to offer? The more this question weighed on me, the more I felt the need to make up for my perceived lack of experience. This translated into my attempt to take on that therapeutic role that is all too comfortable because at least I would be offering something.

After a good night's rest that day, I realized something important: I was not there to fix anything, lighten anyone's burden, or carry emotional weight/pain for others. I was there as Michelle, not as a therapist. In fact, nobody there asked or wanted me to show up as a therapist. The fact that I was selected to attend the conference is proof in itself that there is something that I could offer within the advocacy space, even if I am a "newbie." There is something that I could offer by simply being myself, and I was allowed to be myself (whoever that is). Listening deeply is part of who I am, but absorbing others' pain does not have to be. Once I gave myself permission to let go of the helper role and the imposter syndrome while understanding that I could be present without absorbing everything, something inside of me shifted: I started to share and listen without performing emotional labor.

As a result, my body felt lighter. My energy felt different. As someone who lives with IBD and chronic fatigue as a constant companion, I hardly ever feel energized. Yet in that space, surrounded by community and safety, I felt more awake and alive than I have in years. I slept through the night without restlessness or insomnia, and I rested without guilt. That establishment of safety ultimately allowed my body to shift out of survival mode, which is the foundation of many evidence-based theories. I felt at home in a way I did not expect. I finally saw that I was allowed to accept help and let people in, even if they were going through their own struggles. I saw how support can be mutual and balanced. I also saw how I could be the "supported" instead of the "supporter," especially by how the HealtheVoices organizers took care of me without requiring anything in return. Letting myself step into that truth felt like exhaling after years of holding my breath. It felt like the relief that comes from finally unclenching my fists and jaw. It reminded me how much chronic illness is affected by environment and emotional safety because healing is not only medical, but it is also emotional and communal.

Overall, this experience made me realize how rare it is to just feel safe in everyday life. At HealtheVoices, everyone had something, whether it was a chronic illness, a disability, or the role of being a caregiver. Illness was not the exception. Rather, illness was the normal. By that, I mean that caregivers and those with health challenges were not the minority, and we did not feel out of place. That shift in perspective changed how I saw myself as it made me feel entirely human. Despite my symptoms persisting due to their chronic nature, I did not necessarily feel "disabled." I did not feel "different" or "abnormal." I did not feel like my everyday reality was "too heavy" or "too personal" to be shared. It was simply life, and almost everyone there understood.

The environment created at HealtheVoices highlighted a crucial truth: the world can accommodate people living with chronic illness, but spaces simply choose not to. The conference gathered people with vastly different conditions and needs, and yet everyone I met felt included and supported. This was not magic. This was intention. This was care. This was a commitment to treating people with chronic illness as fully human. I felt that my needs mattered and that I mattered. The organizers did not treat accommodations as burdens but rather as standard practice. This was eye opening because many institutions act as if inclusion is too much work, but this conference proved that it is entirely possible. In fact, it showed me that inclusion is completely achievable when people genuinely want to create it. To put it simply, inclusion is a choice. Dismissing people is also a choice. Institutions, workplaces, and communities can make room for us, but they simply choose not to invest in the effort.

I left the conference with a heart full of gratitude for the connections I made, the stories I heard, the jokes I shared, the insights I gained, and the revitalized sense of identity that I fostered. I left with a deeper understanding of caregiver burden and the emotional landscapes of people living with all types of conditions. I left with the lived experience of how community is essential for healing. I left with a reminder to show up authentically, even in spaces that do not always understand. I left with a deeper commitment to advocate for people with IBD and for people living with chronic illness(es) more broadly. I laughed more than I expected to, and I actually felt real joy. I left with the realization that I often carry emotional burdens for others and take on roles that are not mine to hold, and that realization is going to guide how I move forward in my personal and professional life.

Most of all, I left with a renewed determination to push for environments that truly include people with IBD and other chronic conditions. We deserve to feel normal, included, and valued. We are not abnormal. We are simply made to feel that way by systems that refuse to accommodate us. Anyone can become disabled at any time through illness, accident, age, etc. Anyone can become sick. Anyone can get hurt. Everyone ages (or at least that is the end goal). It is easy to not be concerned about something that does not affect you, but take it from me, it is 100% possible to wake up sick one morning and never be able-bodied again. That is the story of many people with IBD and many people with chronic illnesses. Inclusion matters because disability affects all of us eventually. Anyone can shift into the world that I navigate every day. In turn, inclusion genuinely benefits everyone.

All in all, HealtheVoices reminded me that despite my IBD, I am not alone—I never was. It reminded me that there are some spaces where people like me can feel completely safe, completely understood, and completely ourselves. There are places in the world where people with IBD can feel completely and beautifully at home. Being in such a space where chronic illness and disability is the norm shifted my understanding of what it means to feel "normal." It showed me what true accommodation, accessibility, community, and compassion look like. It showed me what is possible when people choose care over convenience. It proved to me that inclusion is not only possible, but it is deeply worthwhile. I will carry that truth with me and continue advocating for a world that chooses to see us, support us, and welcome us as we are. And for that, I will be forever grateful.

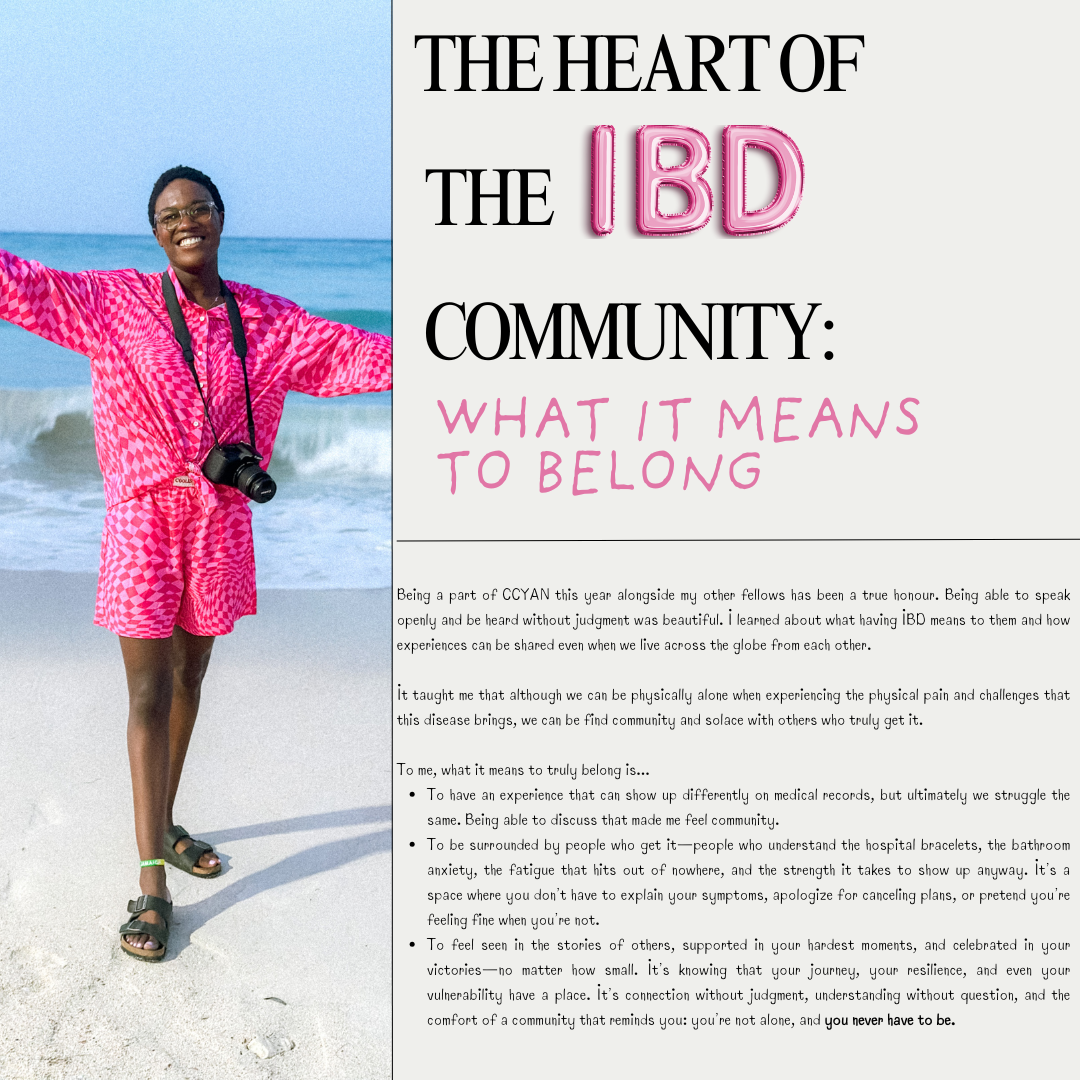

The Heart of the IBD Community: What it Means to Belong

by Lexi Hanson (Missouri, U.S.A.)

Being a part of CCYAN this year alongside my other fellows has been a true honour. Being able to speak openly and be heard without judgment was beautiful. I learned about what having IBD means to them and how experiences can be shared even when we live across the globe from each other.

It taught me that although we can be physically alone when experiencing the physical pain and challenges that this disease brings, we can be find community and solace with others who truly get it.

To me, what it means to truly belong is...

To have an experience that can show up differently on medical records, but ultimately we struggle the same. Being able to discuss that made me feel community.

To be surrounded by people who get it—people who understand the hospital bracelets, the bathroom anxiety, the fatigue that hits out of nowhere, and the strength it takes to show up anyway. It’s a space where you don’t have to explain your symptoms, apologize for canceling plans, or pretend you’re feeling fine when you’re not.

To feel seen in the stories of others, supported in your hardest moments, and celebrated in your victories—no matter how small. It’s knowing that your journey, your resilience, and even your vulnerability have a place. It’s connection without judgment, understanding without question, and the comfort of a community that reminds you: you’re not alone, and you never have to be.

Falsified Empathy in the Workplace: Staying Aware as a Young Adult with Chronic Illness

by Rifa Tusnia Mona (Dhaka, Bangladesh)

As the eldest child, I had the privilege of watching my siblings grow—my brother, six years younger, and my youngest sister, still just a baby. I was there for them whenever my parents were busy, and gradually, without realizing it, I shifted roles. I went from being the one protected on the inner side of the road to being the one who instinctively walked on the outside, protecting others.

By the time I entered university, I felt ready to take on the world. I was driven, ambitious, and full of confidence. It felt like a long-prepared plane finally lifting off the runway—a moment where possibility stretched endlessly ahead.

But just when I thought my life was about to take flight, Crohn’s disease collided with my plans. I barely managed to finish my degree. Before falling ill, I was certain I could secure a job after graduation; I knew my skills and believed they would carry me through. But chronic illness changed that confidence. In my country, remote work often means vulnerability to exploitation, and without my own computer, even that option felt difficult. What frightened me most, however, was burdening my already struggling family with my medical expenses.

There were many moments when I felt my story might end there. I am not someone who easily expresses pain publicly. Yet Crohn’s forced me to ask for help, to depend on others, and in doing so, I discovered something I had never experienced before—what I now call ‘falsified empathy’.

Falsified empathy is empathy that exists only in theory—not in people’s actions. I once worked remotely for a company in Bangladesh. During a month of hospitalization, I unexpectedly received my full salary. But later, HR informed me it was an error and that my next month’s entire salary was deducted because I was unable to work while being hospitalized the previous month. From the next month, I started working remotely and was getting paid half of the salary I got paid while working on site. I raised a complaint, but nothing changed, so I resigned. Company policy required me to work an additional month to ease the transition, which I did— although minimally.

At the end of that month, I went to collect my final month’s payment. The funny part was, when I went to receive the salary, they said that the HR did some wrong calculation and I will still receive some salary from that month! What they didn’t mention was that the amount coincidentally matched the unpaid salary I had earned from my final month of work. In other words, they framed it as an act of understanding and kindness—when in reality, it was merely the payment I was already entitled to. And before leaving, they made sure I signed a non-disclosure agreement.

I share this very personal experience because young people living with chronic illnesses are often vulnerable—and some individuals or organizations may disguise exploitation behind a mask of compassion. They are the “wolves in disguise.” Staying aware and cautious is essential, especially when life puts you in a weakened position.

That’s all from me for this month. Thank you for reading my story. Next month will be my final article of the year, and I promise to bring you something hopeful and uplifting to close the year on a positive note.

Featured photo by Christina & Peter from Pexels.

An overview on Artificial Intelligence in Medical Research

by Akhil Shridhar (India)

As an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) patient and someone who works in the technical field, I'm often curious about the use of new technology in the diagnosis and management of our condition. With seemingly new advancements happening at a breakneck speed, it's hard to keep track of all that's changing, but there's one thing that seems to have everyone's attention. A recent research paper titled "The global academic distribution and changes in research hotspots of artificial intelligence in inflammatory bowel disease since 2000" provides a comprehensive overview of the growing role of Artificial Intelligence in IBD care. In this article we will explore the key findings from the paper, its potential benefits for patients, and important challenges and ethical considerations to keep in mind.

AI in Medical Research

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to computer systems capable of simulating human decision-making skills such as, learning from experience, recognizing complex patterns, making predictions, and even refining their accuracy as new data emerges. Unlike traditional software systems, AI can process massive volumes of medical information from sources such as scans, lab tests, electronic health records, and even genetic sequencing. A practical example in IBD care is AI-powered analysis of colonoscopy images. Here, advanced algorithms can help distinguish subtle signs of inflammation or precancerous changes, sometimes even better than the human eye, leading to earlier and more precise diagnosis. These technologies are not only expanding potential research frontiers but are also beginning to find real-world applications in clinical settings.

Brief summary of the research paper

The reviewed paper takes a global perspective, analyzing more than 1,100 published studies on the interplay between AI and IBD from 2000 to 2024. It demonstrates an exponential increase in AI-related research since 2020, driven by technological advances and the push for precision medicine. American institutions, led by leaders such as Harvard University, have made major contributions, with notable engagement from European and Asian centres as well. The paper identifies several hotspots in AI and IBD that have a high impact:

Radionics: Using AI to interpret medical imaging, especially endoscopy and MRI scans.

Natural Language Processing (NLP): Leveraging AI to extract valuable insights from clinical notes, electronic health records, and even patient self-reports.

Predictive Modelling: AI tools that forecast treatment success, likelihood of complications, and need for surgery, all based on a patient's unique profile.

Genomic and Microbiome Research: Harnessing AI to sift through complex genetic and microbiome data for new biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Personalized Medicine: Integrating diverse patient data streams to create custom care strategies for each IBD patient.

Despite these impressive developments, the paper also points out the need for collaboration between doctors, data scientists, and policymakers to ensure safe and effective implementation.

Benefits for Patients

The true power of AI for patients with IBD lies in its ability to deliver personalized and proactive care, with real-world breakthroughs already emerging. For example, AI-driven systems that analyze colonoscopy images and histological samples in real time are already in use. Physicians now can also use AI models that integrate patient's genetic information, environmental factors, and responses to prior treatments, allowing them to recommend therapies with the highest likelihood of success right from the start. One such machine learning study had accurately predicted response to biologics like infliximab and vedolizumab, minimising delays and reducing risk of adverse effects. Other examples include wearable devices powered by AI that can monitor symptoms and biomarkers continuously, alerting patients and care teams to possible flare-ups before they become too severe. In a very recent ground breaking discovery, researchers at UC San Diego used AI to unravel the cause of chronic inflammation in Crohn's disease after 25 years, revealing the critical role of the NOD2 gene's interaction with a gut protein, Paving the way for new treatments that could directly target the root causes of IBD.

Major clinical trials are now recruiting more diverse patient groups, streamlining data collection, and thus providing tailored interventions thanks to AI algorithms that group participants based on truly representative characteristics. These advances mean patients are no longer just passive recipients of generic care, instead AI allows for better treatment plans that adapt as their condition changes, delivering a future where uncertainty and trial-and-error are replaced by precision, speed, and hope.

Challenges and Ethical Concerns

As with any transformative technology, AI's use in IBD is not without challenges. Large volumes of high-quality, diverse medical data are needed to train reliable AI systems. This reliance raises complex issues regarding data privacy, security, and ownership, patients must be confident that their sensitive health information is protected and not used improperly. Ethical concerns also emerge related to transparency and fairness, patients and clinician need to trust that the algorithms are accurate and unbiased, and able to explain their reasoning in clear and understandable terms. Additionally, there's a critical need for clinicians and engineers to collaborate, ensuring the tools are clinically valid, user-friendly, and integrated seamlessly into everyday practice.

Patients have an important voice in this process. Their engagement can help shape AI systems that uphold dignity, equity, and respect for individuals' needs. Robust ethical oversight and ongoing dialogue will be essential to fully realize the benefits of AI-driven IBD care without unintended consequences.

Conclusion

The integration of AI into the realm of IBD is more than a technological milestone, it represents a profound shift toward truly personalized and proactive patient care. When thoughtfully and ethically implemented, AI can transform how patients experience their diagnosis and treatment by giving them access to faster, more precise answers and by tailoring therapies to fit their unique profile. It can reduce uncertainty, limit experimentation with medications, and empower patients with timely information to manage their health confidently.

For those like us living with IBD, this means not only improved clinical outcomes, but also a higher quality of life, less anxiety, fewer hospital visits, and more meaningful engagement with their healthcare team. With collaboration, transparency, and a patient-first approach, AI has the power to turn hope into progress for those touched by IBD. The ultimate benefit is a healthcare journey that is safer, simpler, and more compassionate with innovation guided by empathy.

Sources:

1. Artificial intelligence in inflammatory bowel disease: Current applications and future directions - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12576597/

2. Distinct colitis-associated macrophages drive NOD2-dependent bacterial sensing and gut homeostasis - https://www.jci.org/articles/view/190851

Image from @lucabravo on Unsplash.