NEWS

“Let It” — My Rule for Living with IBD (Mental Health & IBD Series)

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

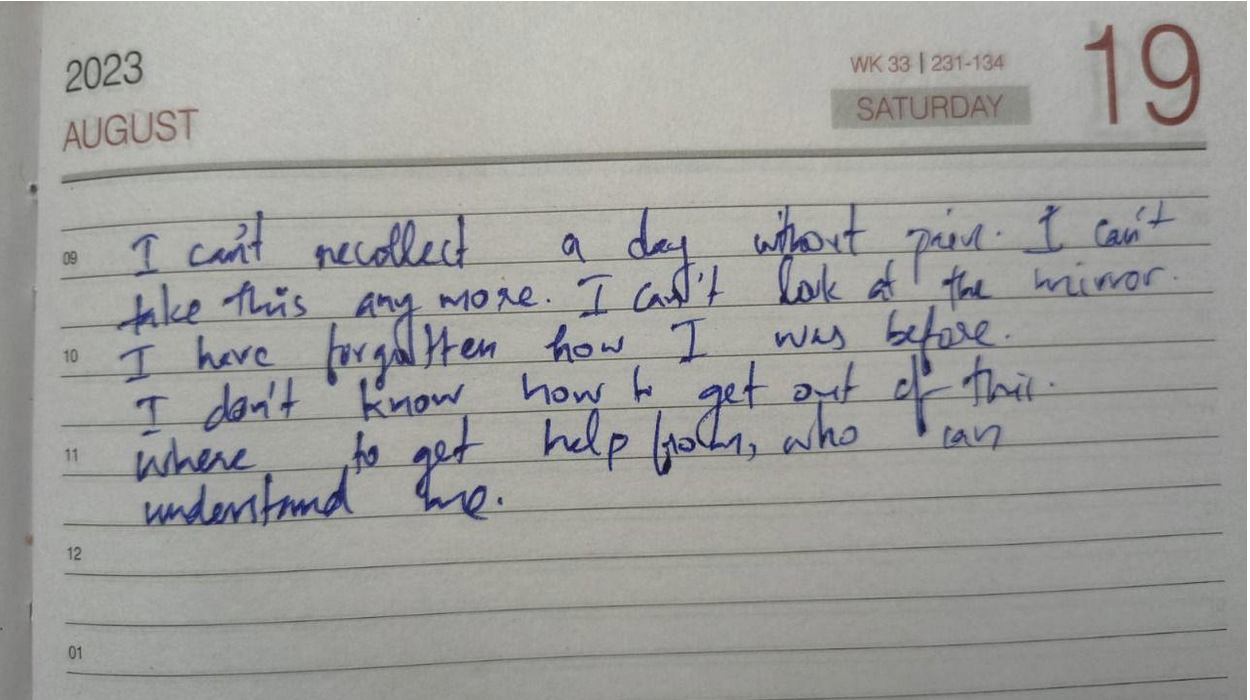

Living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a journey no one truly understands unless they’ve walked it themselves. It changes your body, your mindset, your lifestyle — and even your identity. Over the years, I’ve discovered a rule that helps me rise above the noise, pressure, and pain:

“Let It…”

It reminds me to stop fighting what I can’t change and instead make peace with it — to keep breathing, keep moving, and most of all, keep living.

Let It Be What It Is

IBD is unpredictable. One day you feel okay; the next, you’re back in the hospital.

I remember one exam day when the classroom was overcrowded. I had followed every rule—no phone, fully prepared—but when I arrived, every desk was already taken. There was no seat left for me.

It wasn’t a flare. I had come ready to write the exam, but the conditions made it impossible. I felt angry and frustrated—I had put in the effort, yet I was turned away by circumstances beyond my control. Missing that exam hurt deeply, not only academically but also emotionally. Still, I whispered to myself: “Let it. Everything has a reason.”

Let People Say What They Want

“You don’t look sick.” “Are you sure it’s that serious?” People don’t see what happens behind closed doors — the fatigue, the pain, the hospital visits. Their words used to cut me, but I’ve learned: “I don’t need to prove my pain.”

Let Yourself Say No

There are foods I can’t eat, events I can’t attend, and expectations I can’t meet. I used to feel guilty for saying no, as if I was letting people down. Now I know: “Let yourself say no. It’s not weakness — it’s wisdom.”

Let Hope In

On the hard days, hope is my medicine. Sometimes all I can say to myself is: “Tomorrow is another day.” And that’s enough. Even a tiny spark of hope can carry me through the darkest moments.

Let Go of Pressure

IBD puts pressure on every part of life — physically, emotionally, and socially. I’ve let go of the need to be perfect. If my body tells me to rest, I listen. If I miss something important because of my health, I remind myself: “My health comes first.”

Let Life Be Easier

I no longer compare my life to those who seem to “have it all together.” My peace, joy, and success may look different, and that’s okay: “Let life be gentle, even if it’s not always easy.”

Photo from Unsplash.

Diagnosis is a Light, not a Lamp Shade (Mental Health & IBD Series)

by Aiswarya Asokan (South India)

It was on May 2nd 2016, a day before my 19th birthday, for the first time in my life, I heard the word Crohn’s, from my doctor back then. It came as a scientifically valid explanation to all the so-called “sick drama” I was exhibiting through the years. But the excitement of this achievement soon faded away when I came to know that there is no cure for this. Then came the joint family decision, we will keep this diagnosis a secret to ourselves. Anyways, who is going to accept me if they know I have got a disease that makes me run to the toilet and that I have to be on regular medication to stop this from happening. For the next 4 years, I lived like a criminal, fearing for every breath this crime will be caught. In between, I was ill informed about the dietary restrictions I was supposed to follow, and kept eating triggers from time to time, meanwhile wondering why this is happening – but was still focused on keeping the secret safe.

Still, life was a smooth sail with a few days of bad weather here and there, till 2020, when I had my worst nightmare: a serious flare that left me hospitalized for more than 2 months and unable to take my final year university exams. And my secret was out. Not being able to appear for exams was too much for an academically excellent student like me. I was experiencing such intense pain that I couldn’t even turn sides in bed. All this made me question my identity and shattered my fundamental belief system. None of the medicines were working on me. A group of surgeons visited me, and told me that if surgery was attempted, my life might be over on the table. When I realized I might die soon, I decided to live a little. Even though I was not able to eat anything, I ordered a red velvet cake and ate it. The 2020 Tokyo Olympics were going on – it was my all-time wish to watch the Olympics live, but my academic schedule did not allow me to do so. So from the hospital bed, I watched Neeraj Chopra win a gold medal for India, while all my classmates were taking final year exams.

After a while, steroids started working and I started getting better. At the age of 23, I was 33 kilograms, severely malnourished and on a high dose of medication. I was not afraid to die but coming back to normal life was a challenge. I couldn’t face people nor attend phone calls. Even notifications from messages were alarming for me. I zoned out from everyone around me. I felt myself as a complete failure.

One person kept on calling me, despite me ignoring all their calls, until one day I finally picked up. He was my childhood bestie, who stood with me till I was able to manage things on my own. He made a timetable for me, which included slots for physical activity, exam preparations, and fun activities, and made sure I followed them on a daily basis. Then the exam date came up. There were times when I took supplementary exams alone, in a hall that usually accommodates 60 students. Everyday after the exam, he would ask me how it went, and suggest a movie to watch as a reward for the hard work. After a while, exam results came, and I had the highest score than previous years. Life was again on.

Whenever a flare up hits me, the first thing I notice is a keen desire for physical touch, especially a warm hug, though it sounds strange. I also clench my jaw while asleep, to an extent that my whole face and ears start to hurt the next morning, which further makes it hard to have food. Within the next 3 years, time was up again for a rollercoaster. I had a stricture, unbearable pain, my oral intake was nil, and I had to go for a hemicolectomy. The anticipated complications for the surgery were extremely frightening. This time my boyfriend came up and assured me that “no matter what, I will be there for you.” The surgery went smoothly and I was discharged. I was physically fit but started experiencing PTSD-like symptoms. I started feeling I was just a financial burden to my family.

I slept all day and night as I was not ready to face the thoughts in my head. My boyfriend used to call me every day – just for those few moments I was living, but the rest of the time I used to sleep. This time no friends nor family could help me. Then I started searching for IBD support groups, came to know about IBD India, took the free mental health counselling, and joined the peer group. For the first time, I felt less isolated and felt a sense of belonging. And slowly I replaced my coping mechanism of sleeping with painting. Gradually I was healing, and started feeling more freedom like never before.

Life goes on. Ups and downs are part of it. But when one door closes the other opens. When you feel stuck, ask for help and keep asking until you get one strong enough to pull you out — that is the bravest thing you can do for yourself.

Image from Unsplash.

Listening to Your Body with IBD: The Stoplight System

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

When you're living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), your body becomes its own navigation system. Your body is constantly sending you signals, just like traffic lights do. But unlike the red, yellow, and green lights on the road that we instantly respond to, many of us with IBD have learned to ignore or minimize the "rules" or "drills" that we should follow when our body sends us our own, personal warning signs.

So why is it that we respect a blinking car dashboard, a low battery warning on our electronic devices, and traffic signals/signs more than the signals coming from our own bodies? We wouldn’t ignore our car’s check engine light for weeks (and if we did, we’d expect it to eventually break down). So why do we ignore our body’s warnings? Why don't we listen? As with most things, the answer is complicated.

Here are a few reasons why as people living with IBD, we might forget to listen to these warnings, or try to “push past” them:

Living with IBD means that a few warning lights are always on. That is, we might always have some level of fatigue, bloating, or discomfort. This "always-on" background noise becomes our new normal, and we stop noticing when new signals show up. This is risky because it can lead to ignoring major warning signs or missing slow-building flare-ups.

Our symptoms can become our new normal or "background noise," so we're used to pushing through pain. This means that even when our bodies give us that "red" or "yellow" light signal to slow down or stop due to a symptom/pain that is out of the ordinary, we are still conditioned to push through it. For a lot of us, that is a survival mechanism of having chronic pain (pain that never fully becomes "background noise") in a medical system and society that often tells us to "push through." The world is constructed for those who are able-bodied, and having chronic pain/IBD can force us to sink or swim.

We are often taught to minimize our symptoms, for ourselves and others. Sometimes, doctors dismiss our warning signs, maybe because medical literature doesn't acknowledge all the intricate traffic signals for IBD. Maybe, they're just burned out. Or, maybe doctors—and people in general—can't fully understand the severity of IBD symptoms if they haven't gone through it themselves. Whatever the reason, though, we are conditioned to minimize our symptoms. We are taught that our illness "could be worse." In fact, when explaining IBD to others who don't quite listen closely enough, the false notion that IBD is simply "stomach problems" circulates. So much so that we, ourselves, sometimes say this to others or even believe it ourselves. We don't want to be sick. We wish it was just stomach problems. Being told that our personal traffic lights/signals are simply a result of "anxiety" or "are in our heads" make it easy to eventually believe it ourselves because, why would we want to be sick?

We don’t want to "miss out." Sometimes, we’d rather have a moment of fun—followed by a flare/low-spoons day—than not experience the fun at all. Ignoring the signals can sometimes feel "worth it" since it can give us a small glimpse of what "normal" might be like. We are forever torn between the notions of "respect your body's limits" and "you only live once."

Finding a way to make a choice, despite the consequences, can feel liberating in the short-term. This can look like eating a food that you know isn't "safe" just because you want to make a CHOICE and have autonomy over your own body. As IBD patients, choice is often not in our vocabulary – so pushing through the pain of IBD is often the only way we can feel slightly in control of our own bodies. This is a sense of freedom that we greatly lack as IBD patients.

We don't want to be a “burden.” IBD, in itself, is a burden that we already have to carry. Living with it every day is extremely difficult, and that is an understatement. Even so, we still notice how it affects those around us— our caregivers, partners, family members, friends, co-workers, employers, and even doctors. Carrying the burden alone is never the solution, but it sometimes seems like the right one since it feels wrong to allow someone else to feel even remotely similar to us. It doesn't feel right to allow anyone to be down in the trenches with us—at infusion appointments, at ER visits, at ICU admissions, or at "bathroom sleepovers." It doesn't feel right to allow anyone to feel so wrong, even if they want to. Therefore, we ignore the signs, because if we took action that would mean that we'd need help, whether we like it or not. We'd have to reach out to someone, even if that's just a doctor. Simply alerting your doctor that you've failed another biologic can make you feel like a burden since you might feel as though you're giving them more work. Reaching out to loved ones can be even harder as they will often want to be there for you, and you simply don't want to burden anyone anymore.

We’re afraid of what we’ll find if we stop and really listen. As previously mentioned, we don't want to be sick again. We don't want to discover a new co-morbidity again. We don't want to switch medications again. We don't want to be flaring again. We don't want to go to the hospital again. We don't want to experience medical trauma again. We don't want to put life on pause again. We don't want to miss out again. We don't want to be a burden again. We don't want to lose control again. Listening to your body, and truly paying attention to what it's telling you poses the risk of you having to accept the fact that you might have to go through all of these things again. And at the end of the day, we just want to live—freely. It feels like a constant tug-of-war between surviving and actually living.

The truth is: Your body will always tell you what it needs. It’s just your job to check in—gently and consistently.

Since there is no cure for IBD yet, much of this disease has to do with symptom monitoring and, thus, taking as many preventative measures as possible. I, for one, know that I would like to stay in remission and avoid a flare-up for as long as possible. Even so, I know that's only possible if I listen to my body—genuinely listen. Whether that's taking note of unusual fatigue or nausea, a new sensitivity to food, etc., these are acts of listening to your body and its signals. While we are taught from a young age what traffic lights mean and why it's important to follow them, we aren't taught how to notice and follow the signals that our bodies give us.

A few simple things that you can do to start the practice of ‘checking in’ with yourself and your body:

Create your own ‘traffic light:’ write down some of the signs you notice, when you’re feeling ‘green, yellow, or red!’

Set aside a few minutes each day to ask yourself: What "color" am I today? What makes me that color? What am I feeling, and where am I feeling it? If I’m yellow or red, what needs to change? If I’m green, what can I do to stay there?

Not sure where to start? Here’s an example of my “traffic lights,” and some of the signals I use to check in with myself and my body!

A few things to remember/keep in mind:

Checking in doesn’t mean obsessing. It simply means being mindful enough to care. Just like we do for our phones, our cars, and our jobs—we deserve to offer ourselves the same level of awareness, support, and maintenance.

Living with IBD doesn’t mean you’ll always be stuck in red or yellow. Some days are green—some weeks or months, even. You deserve to honor those days as much as you manage the hard ones.

This stoplight system isn’t about fear. It’s about empowerment. You are not weak for needing rest, medical support, caregiving, or time. You are wise for knowing when to go, when to slow down, and when to stop.

Your body isn’t the enemy—it’s the messenger. Listen to it. Trust it. Respond with love. Your body is doing the best it can to keep you alive. Let’s return the favor.

Image from @tsvetoslav on Unsplash.

What It’s Like Working Through Phobias: Creating A Comfort Toolkit

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

I can't remember a time when I didn't have a blood/needle/medical phobia. I would regularly faint at the doctor's office and even talking about blood was enough to make me pass out in high school. It wasn't a problem until I developed chronic stomach issues and was diagnosed with microscopic colitis. All of the sudden, I was pushed headfirst into a world of doctors' appointments and countless medical tests. It's hard enough to find answers from doctors, but fear can make you ignore your problems, making things worse. I still struggle with this phobia today, but with the help of a therapist, I’m working through my issues. Please seek the help of a trained professional to face your phobias in the safest way possible. Here are several strategies I'm using to make progress facing my fears.

Desensitization Training/ Exposure Therapy

Desensitization and exposure therapy can start with looking at images of videos of your phobia, eventually progressing to more realistic scenarios. For instance, someone with a blood phobia might progress from viewing images to medical shows and eventually going to blood drives. The overall goal might be to get bloodwork done, but you have to build up exposure over time to get more comfortable with your fears.

I've been unknowingly trying to do this my whole life. As a kid, I would reread veterinary books to expose myself to a little literary medical gore. I would deem it a success if I didn't get woozy. Today, medical imagery has become an inherent part of my artistic practice. I find exposure more palatable if I attempt to explore images and procedures from a place of curiosity rather than fear. If I'm looking at veins, I try to ask myself what colors I see under the skin. I've progressed to the point where I can look at surgical photos of arteries and attempt to draw them without getting queasy. It's easier for me to separate myself from a picture than a procedure happening to me, so that's where my exposure therapy has started.

Working with a therapist, I did a deep dive on my phobias and my hierarchy of fears. Instead of just seeing all situations surrounding blood or needles as being equally terrifying, I was able to sort them into a list of situations with varying intensity. While younger me thought a finger prick was the worst situation possible, I now list it much lower on my list, opting to put IVs in a higher position. It's all a matter of perspective. By making a fear hierarchy, I was able to tackle lower intensity situations and gain confidence and resilience before braving my top fears.

Keeping A Sense Of Control

When I was little, my family had to trick me to get me in the doctor's office. In adulthood, I tried to mimic this strategy by being spontaneous. Instead of scheduling a flu shot and worrying about it for weeks in advance, I'd wake up and decide to go that morning. This strategy somewhat lessened my stress, but it also felt too hurried. I never had a sense of control, just urgency to get it done and over with. It didn't leave me in a good headspace and I still found myself fretting over the possibility of getting a shot for weeks ahead of time.

Now, I'm better prepared. With the help of my therapist and journaling, I've made lists of what is within my control during doctors’ appointments. I keep a “comfort bag" ready and always bring it with me to appointments. If I need blood work, I pack my own snacks for afterwards and plan to reward myself with a sweet treat from a nearby cafe. I also pick out my "victim” arm ahead of time based on which arm feels stronger than day.

When it's my turn for bloodwork, I tell my nurse right away that I'm terrified and I'm a faint-risk. I also ask for the reclining chair when possible. It's not so upright that I'll get dizzy and slump over, but through experience, I've also found that fully lying down feels more vulnerable and heightens my fear. A reclining chair puts me in a better headspace, so it is important that I advocate for my preferences. Doing small things consistently and giving yourself small choices in your healthcare can help you feel more in control and you'll know exactly what to expect.

Pack A Comfort Bag, Activate Your Senses

In an effort to ground myself, I try to pack things in my bag that activate my 5 senses of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. I always have these items in a bag and ready to go. Consistency is key, so I bring them with me to all of my medical appointments. When I’m in the waiting room, I grab my headphones and put on some music. I also pack sensory items that are calming like fidget toys to distract myself with. If I’m getting blood drawn, I have a tennis ball handy that I can grip, tissues for when I cry, and a snack for when it’s all over. This kit can be any size and it should be personal to you. Here’s a list of what I keep in my bag:

Snacks

Water

Tissues

Tennis ball (to grip)

Lavender essential oil

Hand warmer

Electrolytes packet

Fidget toy or comfort object (worry stone)

Headphones for calming music or ASMR

Don't Just Wing It, Strategize

Plan out your day ahead of time. Plan to have downtime afterwards to chill, recover, and reward yourself. I like to have a friend or family member drive me to and from appointments just in case I feel dizzy afterwards.

Pressure therapies or tense & release exercises have also been proven to help calm the body. Box breathing is another exercise to keep in your toolkit. It can stop you from hyperventilating and keep you calm. Make sure to try these techniques out BEFORE an appointment or exposure to your phobia. Practice makes perfect and not every therapy works for every person. Find what fits you and make a plan to tackle your phobias.

The Never-Ending Cycle of IBD

By Selan Lee from the United Kingdom

Many things in life are cyclical: the seasons, fashion trends, and the moon’s phases. The one thing we all hope isn’t cyclical is illness. Who wants a never-ending cycle of health and disease? But for those who are chronically ill, it is an unfortunate truth that I previously thought I had accepted - until three months ago.

Three months ago, the symptoms that had started it all returned: frequent diarrhoea, bloating, gas and nausea. In retrospect, stress seems to be a determining factor in my cycle of Crohn’s. My first flare was during the final months of my A-levels - a set of exams that would determine my future according to my 18-year-old self. My second and current flare began two weeks before my graduation and coincided with the final interview for a job I desperately wanted to pass. Unfortunately, the consequences of the stress-inducing circumstances were also cyclical. I severely underperformed in my exams and panic-attacked my way to a re-sit the following year. I didn’t pass the interview and was faced with ending university without a stable job to move on to. Healthwise, like the first flare, I was admitted to the hospital soon after graduation.

Maybe because I had experienced five years of relative good health since my diagnosis, I thought I had accepted the chronic nature of Crohn’s. Despite becoming resistant to a few biologics - I went to university, sourced and worked in a consultancy for my placement year, attended my first concert, joined a panel for young adults with IBD and was able to socialise with friends and family without much concern. My brief period of normalcy had blinded me to the fact I hadn’t really accepted the cyclical nature of my condition, and to be honest, no one with IBD or a chronic illness does.

I remember when someone asked during a panel how people with IBD cope, and the members and I all said hope helped us to cope. Naively, I equated coping with accepting. That’s far from the truth. I can cope with my biologic no longer working as there will be another one. I can cope with waiting for the night shift doctor to prescribe paracetamol for my abdominal pain. I can cope with forgoing foods and situations that will worsen my IBD. But I can’t accept that this will happen again. Understanding and coping are one thing, and acceptance is another.

How can I accept that I will progress through life feeling alone because of my IBD? Like I am sitting on an ice floe floating past all of life’s possibilities. Maybe it is pessimism talking, but living with IBD can be akin to the myth of Sisyphus. Many of us will spend our lives pushing the boulder of IBD to remission - with some, like me, falling back to flare. But maybe, in the words of Albert Camus, I will achieve happiness in this absurd repetition and be satisfied regardless of the outcome. Then again, Captain Raymond Holt says, “Any French philosophy post-Rousseau is essentially a magazine.” [1] - so I will wallow in my pessimism for a while. I might be able to see the brighter perspective of Camus and Terry Jeffords once my new meds prove to be successful.

References

“Brooklyn Nine-Nine” Trying (TV Episode 2020) - IMDB. (n.d.). IMDb. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt10322288/characters/nm0187719

Featured photo by Frank Cone from Pexels.

Stressing about Stress: When Living with IBD

By Maria Rouse from NC, USA

“I’m so stressed.” As a young adult just starting graduate school and recently graduated from undergrad, this common refrain often echoes through hallways, classrooms, and study spaces as a steady hum. Just saying it can create some relief for the stressed person, since putting out into the world that you are stressed is still often stigmatized in academic and workspaces that prioritize competition and elitism. But for a lot of people, especially neurotypical and non-disabled folks, the thinking about stress or the health impacts of it largely ends there for all intents and purposes.

However, for chronically ill people and particularly those with autoimmune diseases like inflammatory bowel disease, thinking about stress quickly compounds on itself and becomes meta: it is so easy to become stressed about your stress knowing how negatively it will impact your health. And it goes without saying that this extra stress is not exactly great for keeping Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis flares under control either.

The primary mechanism through which this works physiologically is that when people with IBD are stressed, perhaps due to a traumatic life event or school/work burnout, our brains release a stress hormone called corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH sends a signal to our adrenal glands to release another group of hormones called glucocorticoids. Glucocorticoids, in turn, then send signals (e.g., colony-stimulating factor 1) that direct immune cells to the intestine that increases the production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) that causes increased intestinal inflammation. And then boom, before you know it and can manage it, you are in the midst of a flare.

I have often found myself jealous of the relative simplicity of stress for people who do not soon become physically ill from its effects on their body. While chronic and/or severe stress generally has negative consequences for peoples’ health down the road (e.g., increased risk of cardiovascular disease, development of chronic conditions such as diabetes), your average person generally does not regularly grapple with these long-term health outcomes on a daily basis until they become acutely present potentially years down the line. There is a privilege in being able to be stressed without being stressed about being stressed. On the other hand, with IBD, folks are more likely to have to grapple with a stressful flare on top of the current stressful situation they are facing. Simply put, when it rains, it pours.

A lot of the well-intentioned but poorly thought-out wellness initiatives now prevalent in workplaces and academic settings will tell you to take deep breaths or practice self-care (what that really means, I still am not sure) to help manage your stress. Anyone with an autoimmune disorder or chronic illness knows, however, that these stress management techniques do not remotely even cover our needs. Stress prevention often needs to be much more comprehensive and planned out in terms of prioritizing activities by the number of spoons (amount of energy) you have that day, consistently getting adequate sleep every night, giving oneself grace and flexibility for not being super productive because of fatigue or a random resurgence of symptoms. It involves taking extra care to avoid chronic condition flares, to the degree we have control over them (i.e., stress levels), early and often.

There is nothing we can fundamentally do to change the fact that having a chronic illness or disability often comes with negative health impacts from stress, which is an inevitable part of life. What we can support changing, however, is the status quo around stress management from something discussed as part of wellness initiatives aimed simply at placating students, employees, and community members seeking greater work-life balance, to an approach of stress prevention. By involving more preventive and intentional techniques (i.e., managing energy levels proactively, intentionally planning ones diet to avoid inflammatory foods), stress prevention can benefit not only the chronically ill and disabled, but also the broader population; as chronically ill and disabled people, we can change the landscape of stress into something that is more intentionally and thoroughly broached in our communities, and by doing so, work to alleviate the stress of being stressed. What is beneficial for those who need accommodations is also beneficial for all.

Sources

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/see-how-stress-affects-inflammatory-bowel-disease/

2. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress-symptoms/art-20050987#:~:text=Common%20effects%20of%20stress,%2C%20stroke%2C%20obesity%20and%20diabetes.

Featured photo by Pedro Figueras from Pexels.

Humour - The Best Defense Against the Realities of Chronic Illness

By Selan Lee from the United Kingdom

In the words of Chandler Bing, “I started using humour as a defence mechanism” - though for me, it is not a consequence of my parents splitting up (just to reassure you, they’re still happily married), but rather a result of my chronic illness.

While there have been difficult moments in my life before and after my Crohn’s diagnosis, I’ve noticed that one of the most significant ways I have coped and helped my loved ones cope with the negativity IBD often brings - is with humour. More often than not, I’m somehow making a joke about poo, the absurdity of hospital scheduling or the horrific taste of Fortisip nutrition shakes. But I had also used humour to make light of bleak health outcomes - for example, when the second of my biologics stopped working, or surgeons tried to push for a stoma just before exams.

As a Psychology undergraduate, I know this technique is a classic example of an emotion-focused coping mechanism in which I utilise humour to manage the stressful emotions that IBD bring. However, I know as a thinking and feeling human being, if I don’t use humour, it is very easy to fall into the grips of the stress and negativity of chronic illness[1] - and similarly for those caring for us[2]. So, I would like to share some moments where I’ve found humour in my experience with chronic illness, and I hope you will find some, too, in your chronic illness journey.

#1 When you're using the same medication as a lady in her 80s -

Any biologic prescribed to someone with IBD has a high probability of also being prescribed to an elderly individual with arthritis. Given that IBD and arthritis are both inflammatory diseases, just attacking different body parts, it makes sense a twenty-something with Crohn’s will be given the same as arthritic Ethel in her 80s. Thus, I find it infinitely hilarious when I walk into the medical day unit and watch as two or three seniors stare at me in curiosity. I’ve seen many an old bitty’s eyes go wide when they hear that I was born in the year 2000. Confusion when the scales reveal I’m on the heavier side and not outwardly weak or frail. But the best bit of this situation, which still makes me chuckle to this day, is what rarely happens at the end of an infusion.

Once an infusion is complete, the IV is removed, and a cotton ball is placed on the site to prevent bleeding. Usually, slight pressure and a little bit of time are enough for a clot to be formed and any chance of bleeding out in a medical bay to be reduced to virtually zero. However, on one rare occasion, not enough was applied, and as I got up to gather my things - I felt a warm sensation over the back of my hand. Looking down, I noticed a few drops of blood on the back of my phone case and some staining on the denim of my jeans. Turning to look at my hand, I realised the warm sensation was not my hand warming up after the cold IV stream - but blood oozing out from the infusion site. My hand looked like a Halloween decoration. Perhaps as a result of my lack of aversion to blood or my fatigue, I quietly and calmly asked the nurse for help. What I didn’t realise until I stood there waiting as the nurses scrambled to get the gauze or alcohol wipes was that arthritic Ethel had witnessed a young whippersnapper with a bleeding hand look at said bleeding hand with no fear and simply say, “Excuse me” as I pointed with my non-bleeding hand to the bloodbath - like a complete psychopath. I saw a look of horror and fear of myself, not the blood, in her eyes, and it still makes me laugh to know that she probably told everyone she knew about the psychopathic twenty-something she met in the medical day unit.

#2 A little too familiar with the Bristol Stool Scale -

It is a right of passage to be introduced to the Bristol Stool Scale following a diagnosis of IBD, with 1 being akin to rabbit droppings and 7 to swamp water. My mum quickly started using numbers to check my condition after this introduction. In the early days of a flare, I would be asked, “Number 4, 5 or 6?” as soon as I left the bathroom. However, it also became a way for us to assess unappetising food: a dodgy-looking shepherd’s pie, a 5. A little too watery chocolate lava cake, a 7. It didn’t take too long for us to realise that this scale may not be as appetising to overhear at the dinner table as it was funny for us to quip.

#3 The best way to enjoy a Pepsi is without the fizz -

You develop a strange relationship with food when you have IBD, and for me, during a flare or in the few weeks leading to my infusions, I find fizzy drinks hard on the gut. The carbon dioxide seems to exacerbate the pain and discomfort. But that doesn’t mean the cravings for certain beverages disappear.

On one such occasion during my flare, I craved a Pepsi - but didn’t want the fizziness it came with. Thus, I hatched a plan. As my parents were preparing to leave for Costco while I convalesced at home, I told them it would be a good idea to get some food, preferably a hot dog, to enjoy themselves and our dog. They returned with hot dogs and, more importantly, cups filled with Pepsi. While they enjoyed their food, I kept an eye on my Dad’s Pepsi. I knew he would have drunk a cup at the store, and this was his refill. I also knew that he never fully finished his second cup of Pepsi. Therefore, I waited for the moment he inevitably left the partially-full cup on the table. Once he left the table, I took the cup, checked the contents and once satisfied - I hid the cup in the fridge behind some condiments. The next day, I gleefully took out the flat Pepsi and downed the drink without the slightest hint of effervescence. I have yet to have a similarly satisfying food or drink experience.

References

Naylor, Chris & Parsonage, Michael & McDaid, David & Knapp, Martin & Fossey, Matt & A, Galea. (2012). Long-Term Conditions and Mental Health: The Cost of Co-Morbidities. https://assets.kingsfund.org.uk/f/256914/x/a7a77f9f6b/long_term_conditions_and_mental_health_february_2012.pdf

Lim, Jw., Zebrack, B. Caring for family members with chronic physical illness: A critical review of caregiver literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2, 50 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-50

Featured photo by Fernanda Lima from Pexels

Bittersweet Road to Recovery

By Maalvika Bhuvansunder

Recovery is a word that can be seen as both, something positive and negative. On one hand, recovery signifies better times, better life ahead, and no more pain. However, it also reminds us of what we had to lose in the process, the reality that we had something we needed to recover from, and a lot of other things. Recovery is even scarier when we do not know if it would last long or if it is just the calm before the storm.

My already low self-esteem took an even more downward spiral.

During our journey of recovery, we might not be our best selves. There is a lot we might have given up and the loss feels more real when we are healthier. Post my surgery and remission I started comparing my journey with others and started realizing all the ways I have been lacking behind. My career was on hold for the two years that I was in a horrible flare, my master's grades were not as great due to my flares, and my social life was practically non-existent. My already low self-esteem took an even more downward spiral, which was surprising, as I had expected being in remission would help improve my self-esteem. What did not help were comments of people saying finally I would stop crying all the time or that at least now I can start having a career. I started comparing myself to those my age and started resenting myself for not being where they were. In this process, I was becoming a bitter person who was unhappy with others' success and was wallowing in self-pity.

A year ago I could not get out of bed or eat a single morsel of food. Now, I am healthier, able to eat what I love, and do things I have wanted to do.

What I forgot to realize was that being in remission is my growth! A year ago I could not get out of bed or eat a single morsel of food. Now, I am healthier, able to eat what I love, and do things I have wanted to do. This is a huge accomplishment for anyone with a chronic illness! I did some self-reflection and realized I was being too harsh on myself. I am a part of a fellowship that helps others like me and I realized how big of an accomplishment this is! There is no fixed definition of growth and success. Instead of feeling bitter over others' success, I started being a part of their happiness. They were there for me when I was at my lowest, so it is my turn to be there for them. I started celebrating the small successes in my life and it made me feel proud of myself. One of the steps to recovering was accepting the fact that it is okay if I am not on the same path as others, as my journey is my own and is unique. Our bodies have been through a lot, so the fact that we can function with all the pain is a huge accomplishment. Our society is always going to have this “fixed” measurement of success. However, setting my definition of growth and success made me feel free and liberated.

“Each person has their journey and there is no fixed timeline for achieving goals in life.”

Saying No is Ok!

By Isabela Hernandez (Florida, USA)

There are going to be days when your IBD is acting up, and you do not feel up to going to events or seeing friends you’ve committed to seeing. Yet, you feel guilty for saying you don’t feel well. I used to struggle with this heavily. I would have a plan with friends that was made in advance, but the morning of, I’d wake up feeling extremely sick. Many thoughts would be going through my head. Do I go and stay in pain? Do I say I’m sick; would they believe me if I say I’m sick? Why do I feel guilty for changing my mind? I would try to explain to the people around me how I was feeling, but I could see in their faces they didn’t really understand how intensely my IBD affects me, especially socially. To them, me saying no was me bailing on spending quality time with friends for selfish reasons. For me, saying no was the only way I could preserve the sanctity of my physical and mental health. These experiences with friends have taught me many things.

There is NO reason we need to feel guilty for prioritizing our health, whether that be saying no to a friend or backing out of a plan last minute due to symptoms.

If your friends don’t try to understand how your IBD affects your life socially, then it may be time to reevaluate what these friendships mean to you.

Find healthy ways to communicate with the people you are close with to let them better understand your IBD - if you don’t let them in, they’ll never truly get to know you and your disease.

Be open with YOURSELF about what you feel and adjust your day based on that. Everyday is different and that’s ok.

Do what’s best for you!

Now, those around me know when I say, “I’m having some symptoms today, I don’t think I can go,” that it is not personal, but I need to focus on myself that day. I’ve found people who have learned to respect that and really understand what I feel. I challenge you to put yourself first and learn to prioritize your health, even when it’s hard.

This article is sponsored by Trellus

Trellus envisions a world where every person with a chronic condition has hope and thrives. Their mission is to elevate the quality and delivery of expert-driven personalized care for people with chronic conditions by fostering resilience, cultivating learning, and connecting all partners in care.

My Journey with Health PTSD

By Maalvika Bhuvansunder

World mental health day was marked on the 10th of October. In today’s world, there is a lot more awareness and acceptance regarding mental health concerns. However, not much is spoken about the relationship between having a physical illness and its impact on one’s mental health, or vice versa. I have always been very vocal about accepting and understanding mental illness and aim to be an advocate for those going through it. Being a student of psychology and hopefully a future psychologist, I felt it was my duty to contribute to destigmatizing mental illness. What I never expected was that I would have to be my advocate as well!

2017 was a very difficult year for me, there were a lot of new changes happening, from getting my diagnosis, to learning how to cope with it. My mental health was getting affected since then itself, but I was unable to recognize those signs. During my non-flare-up days, I’d still not be calm, because subconsciously I was always expecting a relapse or something to go bad. I would constantly overthink and worry, which was very unlikely of me. I started finding comfort in anger. Since I had no control over what was happening to me, Anger was the emotion I would always resort to because being happy caused me a lot of anxiety. Whenever there was a situation that went well and made me feel happy, after a few minutes I would be filled with the dread of something going wrong. I could never make impromptu plans, and any change in routine would get me to spiral into a state of anxiety.

“Since I had no control over what was happening to me, anger was the emotion I would always resort to because being happy caused me a lot of anxiety. ”

Starting to notice that these emotions and feelings were not just stress, I did my research. I realised what I was experiencing could be Health Related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (Health- PTSD). It is commonly seen in individuals who are going through a lifelong illness (1). This was surprising to me, as being from the mental health field, I assumed PTSD only relates to extreme trauma in life, not realizing in a way, having Crohn's was my trauma. I was experiencing the anxiety of the surgery and reports indicating a relapse, the depression of the flare-ups, the grief of losing myself, and the fear of being hospitalised. I was experiencing this more once I reached remission, which made sense as I was experiencing it post-trauma. The trauma of the pain, of not being able to eat what I love, hating the way I looked, having zero social life, and many others. We do not realise how much an illness can impact you overall. Crohn's is more than just a physical illness.

My experience made me realise how important it is to advocate for this. I took the step of seeking help and was lucky to understand the signs, albeit a bit later. However, not everybody can recognize these signs, especially as there is not much awareness about the coexisting relationship between physical and mental health. PTSD is not just limited to the most spoken-about traumas. Trauma is trauma, the magnitude of it should not be a determining factor. It is okay to ask for help and seek help. We are always going to hear comments like, “you are depressed because of this?” or “people have it worse”, but don't let that stop you from seeking help. Only we know what we are going through and have to be our advocates!

(1) Pietrzak, R. H., Goldstein, R. B., Southwick, S. M., & Grant, B. F. (2012). Physical health conditions associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in U.S. older adults: results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society,60(2), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03788.x