NEWS

Some Things You Learn to Accept Without Questions

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Sometimes there are things in life you learn to accept without asking why. For me, asking questions only made the stress worse, and stress only made my illness harder to survive.

I was diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when I was very young. Looking back now, I can see how different I was from other children. I was always tired, weak, and running out of energy. While others played and dreamed freely, my body felt heavy, as if it was always asking me to slow down.

School was especially hard. Learning took more effort than I could explain, and there were moments when my body completely failed me. I remember fainting during exams—lying there while the world blurred around me, carrying not only pain but deep embarrassment. Being different from your classmates hurts in ways words can’t easily describe. It makes you feel invisible and exposed at the same time.

There were many days I cried alone. Not being able to do what you want as a child slowly takes away your hope. I watched my classmates move forward while I felt stuck, left behind by a body I didn’t understand. I began to believe that maybe I would never become “someone.”

IBD didn’t just affect me—it affected my family too. I saw their worry, their sacrifices, and their quiet strength. Watching the people you love struggle because of your illness leaves a mark on your heart that never fully fades.

For a long time, I didn’t have the words to explain what I was going through. When people said, “I have no words,” I never understood it. Now I do. My own words were scared. They hid behind silence, afraid to come out.

IBD delayed my education, interrupted my plans, and shook my confidence. But it did not destroy me.

What I have learned is that resilience grows quietly. Hope doesn’t always arrive loudly—it sometimes appears in the simple act of waking up and trying again. Even when the path feels unbearable, even when progress is slow, survival itself becomes an act of courage.

Yes, I am later than others.

But I am not behind.

I am surviving something incredibly hard, and I am still standing.

Today, I am a woman with a past shaped by pain, a heart filled with empathy, and a future that has not been canceled. My journey may look different, but it still matters. And if my story can help someone feel less alone, then every difficult step has meaning.

Featured image from Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash.

Reflections on AIBD 2025

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

In early December, I had the privilege of attending the Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (AIBD) conference in Orlando, Florida. While trying to describe my experience, the words that keep coming to mind are “life-affirming.” I couldn't be more grateful to be in a space surrounded by doctors who were passionate about IBD treatment and driven to learn the newest research in the field.

My entire experience with CCYAN has made me rethink my experiences as a patient and what I need from my doctors. The thing I seemed to be missing most was the WHY behind their decisions and treatment recommendations. I know appointments are brief, but knowing the reasoning behind the drugs prescribed or questions asked would have made me trust a few of my previous gastroenterologists a little more. As someone diagnosed with Microscopic Colitis (MC) who was on steroids for years, it was incredibly validating to hear the experts at AIBD acknowledge that steroids are dangerous and should only be a short term solution as a bridge to another treatment. They also recommended steroid use sparingly and tapering whenever possible. It was also interesting to learn about which drugs are first or second line drugs in the treatment of IBD. Sometimes, it can feel like doctors just throw drugs at us waiting for the right one to stick. I liked being able to see that there was a set plan and procedure for treatment options in place.

A refreshing update the conference covered was their take on anxiety and depression. They said that all gastroenterologists should be asking their patients if they're experiencing anxiety or depression. I learned that having one or both of these can affect medication compliance and drug effectiveness. The conference speakers pushed the importance of prehabilitation - preparing the patient pre-op to optimize outcomes. Prehabilitation does more than just help surgical outcomes, according to studies done by Dr. Gil Melmed, it can save hospitals thousands of dollars in the long run. Another important note mentioned early on at AIBD was that vaping and e-cigarette use are a significant risk factor for post-operative recurrence and poorer overall outcomes. Doctors also acknowledged that although IBD patients sometimes say they are doing “well," it may not necessarily mean “well" by normal standards. It can mean a lot of things such as infrequent bouts of symptoms, symptoms that don't interfere much with their daily life, or symptoms that vary or subside after a while. By digging deeper and having open discussions with their patients, doctors can gather more helpful information and set their patients up with the necessary resources.

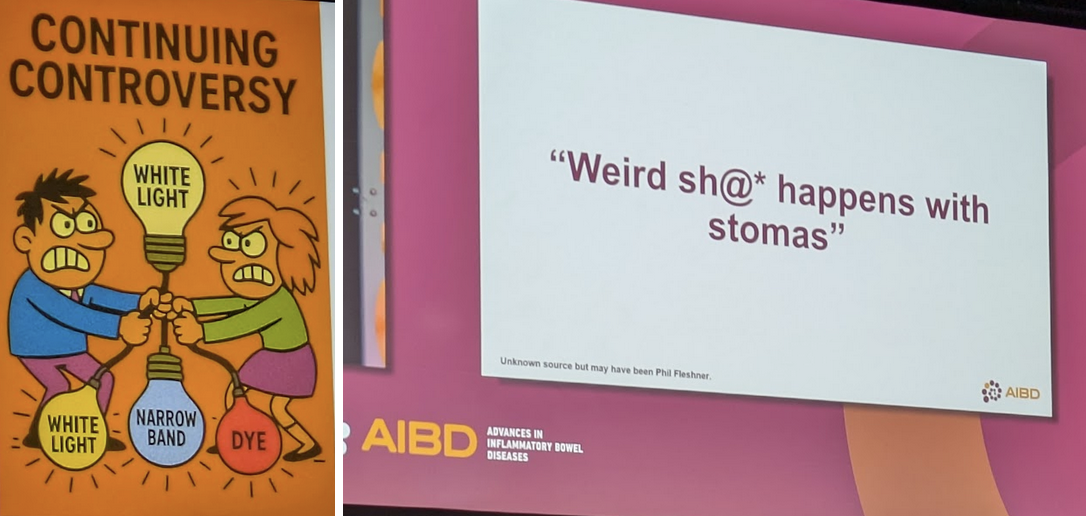

I also loved seeing the doctors’ personalities come out at the conference. From showing powerpoints reading “weird sh@* happens with stomas” to hearing surgeons argue over their preferred method of stitching up a pouch, it was refreshing to see their passion and silliness. Some speakers’ PowerPoints were more serious with surgical photos and case studies while others used fun slogans and humorous cartoon graphics to get their points across.

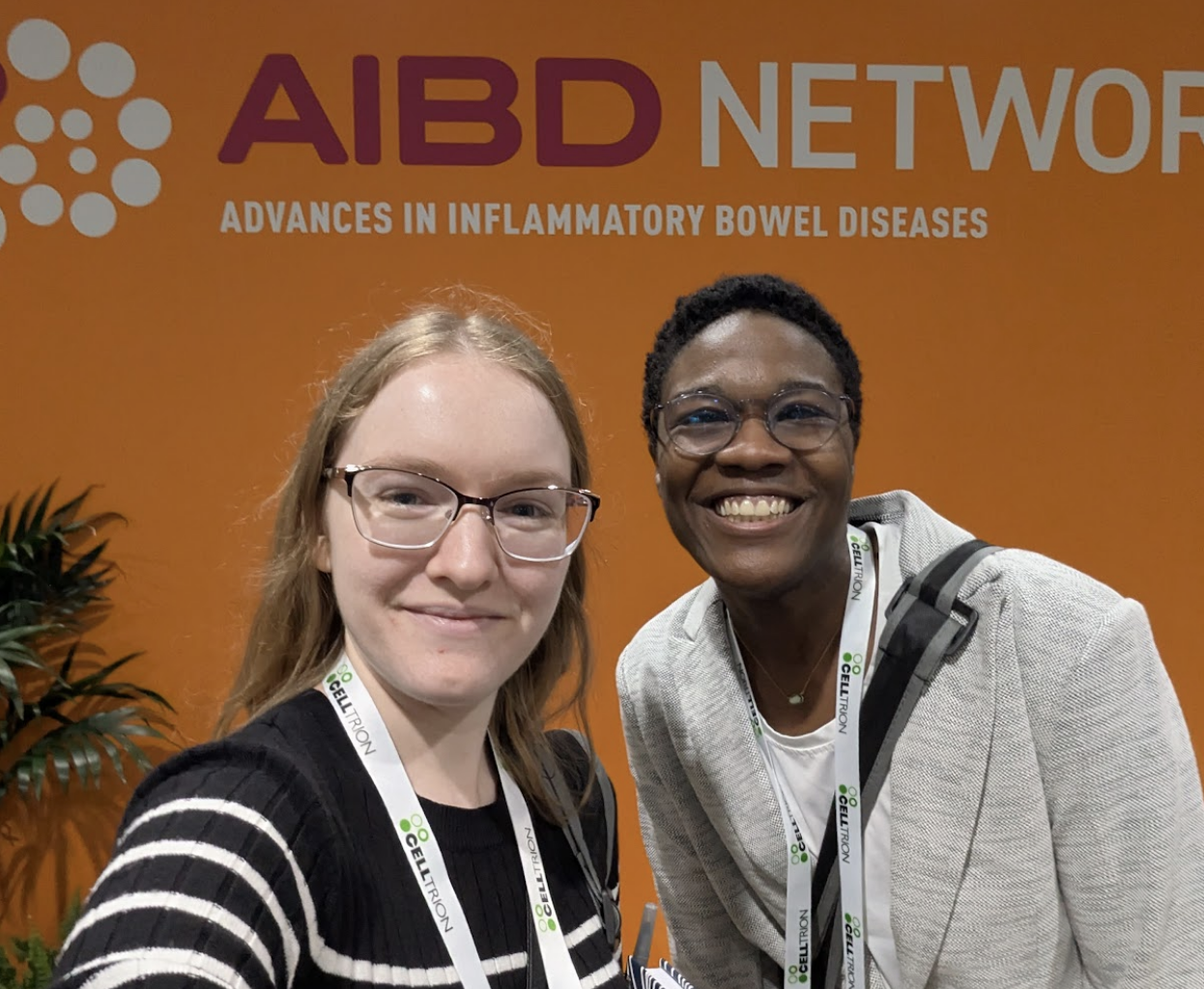

On a personal level, this was my first experience traveling independently across the country. I flew to Florida, navigated the airports, took Ubers, and even took a solo trip to Disney for a day. Despite a few hiccups along the way, (I’M LOOKING AT YOU BROKEN TOILET PIPE), this trip gave me an immense sense of accomplishment and confidence that I can figure things out for myself. I'm hoping to take my newfound independence to new heights in 2026 and go on many more solo adventures. I'm so glad I got the chance to meet Lexi, another CCYAN 2025 fellow, who has such a positive and lighthearted presence. I love how she takes everything in stride and I hope to have her boundless energy one day. I also met CCYAN alumni Mara and Grady (and of course Mara’s service dog Rooster) as well as CCYAN founder Sneha. They were the best group I could have asked for and they were so supportive when I flared during the last day of the trip.

I can also definitively say that there will be more medical conferences in my future. I’m not exaggerating when I say AIBD was more fun for me than Disneyworld. Getting the chance to attend any and all lectures I wanted was a dream come true! I went to every surgical track lecture, just for the fun of it. I took pages upon pages of notes and came up with a very hefty list of vocabulary words to research for next time. Being at the medical lectures just felt so right. As a teacher, one of my top goals is to develop every child into a lifelong learner - someone who stays inquisitive and follows their passion long after they receive their diploma. I hope I have successfully modeled that for my students and continue to do so. It was amazing to be in a room of a thousand lifelong learners who all want to hone their practice and be better-informed when treating their IBD patients.

Thank you again to CCYAN for this amazing opportunity and for connecting us all into one big IBD family. I'm forever grateful. As they say in Hamilton, “I wanna be in the room where it happens...I've GOT to be in the room where it happens”. Until next time…

Farewell 2025 — A Journey of Self-Discovery, Resilience, and Growth

by Rifa Tusnia Mona (Dhaka, Bangladesh)

I can’t believe 2026 is already here! There are so many things that feel surreal to me actually. After having crohn’s, I was bedridden for a long time. While looking at the white plastered roof upside, I knew I was stuck in my life. I didn’t have a terminal illness which meant I wasn’t dying! But, with frequent flare-ups, cramps, weight-loss, and hospitalization reminded me that normal life wasn’t possible either. At some point, I felt blank inside. I remember when someone would ask what I am planning to do with my future, I would say, close your eyes and you will see! They would say it’s pitch black when I close my eyes! Then I would hilariously say, Correct! That’s my future! And that would’ve been true until I decided to finally get up and go all-out. I often say to my mom, ‘Ammu, even if there was an ounce less pain, I wouldn’t have gotten where I am now!’ I felt graceful to god as the pains were coming from all directions and at some point they became the reason for my living.

In the past few months, I boarded a plane six times, traveled to India twice from Bangladesh, and moved to a different continent! To Europe, in Lisbon, far away from the comfort zone of my room, my bed!

I have very small veins, and my body does not absorb oral medications effectively, which made the intravenous treatment particularly challenging. There were days when cannulation was urgently required, yet despite repeated attempts throughout the day, the nurses were unable to locate a suitable vein. By the end of those days, my hands were so exhausted and numb that I could barely feel them anymore.

By this time, the hospital feels like a second home! I got married to Crohn’s and the hospital became my in-laws! Funny, right!

Despite everything, I remain grateful. I am currently at the closing stage of my first semester of my Master’s program in Lisbon, and as part of the mobility track of the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master’s program, I will be moving to the Netherlands in February. The travel plan is almost ready and I am confident that I can do it.

Living with Crohn’s disease has reshaped my sense of fear. When survival itself becomes the central challenge, traditional definitions of success begin to fade. That is what happened to me. Compared to where I once stood, I am no longer simply enduring life; I am moving forward with purpose. That, above all, is what matters to me.

I’ll keep this brief, as I’m currently admitted to H.S.A. Capuchos Hospital, Lisbon, due to a recent flare-up. I’m not sure if my words will inspire, but if even one person feels a little encouraged after reading my story, it will mean the world to me. I am deeply grateful to CCYAN for giving me a platform to share my story, my voice, and my true feelings. I hope the new year brings a fresh start for everyone, filled with love and happiness. Thank you for reading!

Featured photo: A photo of me in front of the university gate taken by my beautiful friend, Hiba Hamada.

HealtheVoices 2025: Feeling Beautifully at Home with my IBD

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

Disclaimer from Michelle: Johnson & Johnson paid for my travel expenses to attend HealtheVoices, but all thoughts and opinions expressed here are my own. This conference was not attended as a part of the CCYAN fellowship.

From November 6th through November 9th, 2025, I stepped into a space that I had never experienced before. HealtheVoices 2025 was more than a conference for advocates like me. HealtheVoices became a place where my body, story, and heart finally felt understood. I walked in as an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and mental health advocate, but I walked out feeling like I had reclaimed parts of myself that IBD had slowly worn down.

IBD affects so much more than the digestive system. My life is shaped by symptoms that are unpredictable and exhausting, with my mental health experiences running parallel to this journey and adding additional weight. IBD ultimately shapes the way that I move through the world, my energy, my confidence, and even the level of honesty that I bring to conversations. Daily life can feel even more heavy and lonely because it is rare for me to be in a room filled with people who truly understand what chronic illness feels like, and vulnerability about illness does not always land well with people who cannot relate. At HealtheVoices, that weight softened the very moment that I arrived. The environment made me feel safe before I even realized that I had been holding my breath for so long.

I met people living with many types of chronic conditions, from visible disabilities to more silent illnesses like mine. I met caregivers who understood illness from the position of love and exhaustion. I met people who shared my diagnosis of IBD and people who shared my mental health struggles as well. In turn, I finally did not feel like the odd one out or like the only person in the room fighting a battle that no one else could see. For one weekend, I felt truly seen, understood, and supported. It felt like everyone there spoke a language that I always knew but rarely had spoken back to me. It was a rare and profound reminder that community, safety, and understanding can change the way a chronically ill body feels because, to put it simply, I finally felt normal.

While I cannot speak for all of the attendees, I know that I felt this way for a variety of reasons, and I am going to try my best to put it into words.

For starters, I could tell that the conference itself was intentionally designed with us in mind, and that intention showed in every detail. Organizers checked-in on us often, encouraged rest, and made it clear that nothing was mandatory. They understood that rest is both a need and a responsibility. They understood that pushing too hard could cause flare ups, particularly for those of us with IBD or conditions that involve fatigue, pain, and unpredictable symptoms. Even travel was supported as I received reminders and check-ins to make sure that I made it to my flight safely. This took the emotional labor out of the small things that usually drain me, and their help and accommodations were never made to feel like favors. Plus, everything was optional, yet everything was thoughtfully provided. It was all offered with genuine care, and that is something that I rarely feel in spaces outside the chronic illness community. I truly felt taken care of at every moment. I never felt pressured to show up to an event, and I never felt like a burden or a "waste of an attendee" if I did not. I felt valued simply because of who I am, IBD and all. Typically, I am made to feel as though my IBD devalues me throughout many domains of life, but I felt the opposite way while at HealtheVoices. I also felt considered and looked out for without being pitied or restricted. In other words, I felt empowered to take care of myself and to be the advocate I want to be, while also realizing that there is power in accepting help and care—there is the "power of us."

Regarding this "power of us," I was able to witness and experience how chronic illness can foster unity, even when diagnoses and symptoms may differ. This was exhibited right off-the-bat at the very first dinner of the conference when attendees were grouped based on their health condition, and I accidentally sat with the mental health and pulmonary hypertension group instead of the immunology group. What started as an awkward mistake due to my brain fog after a long day of traveling ended up turning into a gift. At this dinner, I connected with people who understood my mental health story in ways that felt grounding and familiar. Some even worked in the mental health field like I do, which felt incredibly validating. Therefore, even though not a single individual there had IBD, our emotional landscapes were still strikingly similar. We each shared our stories of career challenges, burnout, medical dismissal, discrimination, chronic pain, hospital admissions, fatigue, chosen family, the exhaustion of being misunderstood, and the emotional toll of navigating life and relationships with an unpredictable body and/or mind. We also connected over experiences specific to gender, such as being dismissed in medical settings until a male caregiver shows up.

These discussions reminded me that chronic illness is not defined only by biology. It is shaped by stigma, gender, identity, socioeconomic realities, and the emotional toll of constantly having to justify our experiences. Even people whose conditions had nothing in common with mine understood the same nuances of fatigue, pain, fear, and perseverance. Our hearts carried extremely similar stories, and the overlap was both comforting and heart-wrenching at the same time.

After that realization, I made a conscious effort for the rest of the weekend to approach people without looking at their badges. I did not want to lead with diagnoses anymore since I understood that a diagnosis was not the only thing that could foster deep connections. I wanted to understand people for who they were rather than for what condition they advocated for, even though I understood that advocacy often played a large role in the attendees' identities.

Despite it being an advocacy conference, my goal was not to advocate or educate that weekend. I simply wanted honest connection. I wanted to feel safe being myself. I wanted to meet people who would understand both the heaviness and the humor that come with living in a body that needs extra care and requires constant negotiation, without limiting myself by my diagnosis. My IBD has limited me enough already, and I was not going to let it stop me from making the meaningful connections that I have been seeking just because of a label. As it is, living with IBD and mental health challenges is incredibly isolating, especially when daily experiences and honesty are treated as oversharing. Everyone, including myself, preaches vulnerability, but it is difficult to be vulnerable when people do not know how to respond or cannot relate to your daily reality. That is why having the space to openly share about your day-to-day life—without the sugarcoating—is essential, and I found that space with each and every attendee carrying all of the diagnoses under the sun. It did not matter if they had IBD, a different chronic illness, or if they were a caregiver since we could all relate to one another in some way.

This was an incredible phenomenon that attendees and I noticed since at HealtheVoices, we did not have to explain the basics. Each conversation started with an innate understanding of one another. This understanding was not just based in compassion and shared experiences as it was oftentimes also based in shared medical knowledge/terminology, tips and tricks for navigating the healthcare system, etc. This is because everyone there lived some version of the same complexity. For example, many of the attendees understood Prednisone's mental and emotional side effects, sometimes even making light of it nonchalantly during conversations. Outside of the chronic illness space, these jokes and statements would have to be explained or given some background information, which can become exhausting over time, especially as you meet more people throughout your life. Having people who just "get" certain things—without needing to pause the conversation to explain and without having to worry about how it might be taken—is a breath of fresh air.

I did not have to soften the truth or worry about being labeled as "dramatic" or "negative." I did not have to explain why I left an event early or arrived late, nor did I have to explain why I did not finish the food on my plate. People just got it. This conference felt like a safe haven where I did not have to justify my needs or my existence as someone living with IBD. Even when we were not familiar with aspects of each other's health condition(s), we approached one another with curiosity rather than making assumptions, offering unsolicited medical advice or "natural remedies" that we have likely already tried/been advised to try countless times, or making remarks along the lines of, "everything happens for a reason" and "at least it's not cancer."

Conversations were honest but never forced, and I found that our weekend did not revolve entirely around illness. Sure, we cried a lot, but we also laughed a lot. We talked about hobbies, goals, spirituality, tarot, and things that were not centered in our diagnoses. It felt balanced in a way that my everyday life rarely does since either my whole world feels tied to my IBD, or I attempt to live in denial of its existence. At HealtheVoices, I did not have to shrink or edit my truth.

Yet, there was a moment very early into the weekend when I felt myself growing emotionally tired. While there were those intriguing conversations outside of chronic illness, most conversations were still deep and personal in nature. As a result, I felt an unexpected countertransference building inside of me, as if I had automatically tried to become the "listener" and "helper." Hearing such heavy stories that mirrored my own felt draining at first because I empathized deeply, and I wanted to hold people's burdens for them for as long as I could. That is what I am used to doing for others, and that is what I honestly enjoy doing. I see it as a privilege to be trusted with such personal information and stories of deep pain. Thus, I wanted to show my gratitude for this privilege, which expressed itself as me unconsciously attempting to relieve some of their burdens. It was as if I had naturally tried to step into the role of "therapist" instead of simply being myself. It is a habit that comes naturally to me, especially since I am entering the mental health field as a therapist and hope to work with people who have chronic illnesses.

I also initially experienced some imposter syndrome early into the conference. I was surrounded by these incredible advocates, many of whom have been advocating for decades. Some were even making a career out of their advocacy journeys. Even though it feels like IBD has been a part of my identity for my whole life, I was only diagnosed 4.5 years ago. Similarly, even though I feel as though I have been advocating for years, I really have only been actively advocating and becoming involved in the IBD community this past year. This made me begin to question why I was selected to attend the conference. What the heck do I have to offer? The more this question weighed on me, the more I felt the need to make up for my perceived lack of experience. This translated into my attempt to take on that therapeutic role that is all too comfortable because at least I would be offering something.

After a good night's rest that day, I realized something important: I was not there to fix anything, lighten anyone's burden, or carry emotional weight/pain for others. I was there as Michelle, not as a therapist. In fact, nobody there asked or wanted me to show up as a therapist. The fact that I was selected to attend the conference is proof in itself that there is something that I could offer within the advocacy space, even if I am a "newbie." There is something that I could offer by simply being myself, and I was allowed to be myself (whoever that is). Listening deeply is part of who I am, but absorbing others' pain does not have to be. Once I gave myself permission to let go of the helper role and the imposter syndrome while understanding that I could be present without absorbing everything, something inside of me shifted: I started to share and listen without performing emotional labor.

As a result, my body felt lighter. My energy felt different. As someone who lives with IBD and chronic fatigue as a constant companion, I hardly ever feel energized. Yet in that space, surrounded by community and safety, I felt more awake and alive than I have in years. I slept through the night without restlessness or insomnia, and I rested without guilt. That establishment of safety ultimately allowed my body to shift out of survival mode, which is the foundation of many evidence-based theories. I felt at home in a way I did not expect. I finally saw that I was allowed to accept help and let people in, even if they were going through their own struggles. I saw how support can be mutual and balanced. I also saw how I could be the "supported" instead of the "supporter," especially by how the HealtheVoices organizers took care of me without requiring anything in return. Letting myself step into that truth felt like exhaling after years of holding my breath. It felt like the relief that comes from finally unclenching my fists and jaw. It reminded me how much chronic illness is affected by environment and emotional safety because healing is not only medical, but it is also emotional and communal.

Overall, this experience made me realize how rare it is to just feel safe in everyday life. At HealtheVoices, everyone had something, whether it was a chronic illness, a disability, or the role of being a caregiver. Illness was not the exception. Rather, illness was the normal. By that, I mean that caregivers and those with health challenges were not the minority, and we did not feel out of place. That shift in perspective changed how I saw myself as it made me feel entirely human. Despite my symptoms persisting due to their chronic nature, I did not necessarily feel "disabled." I did not feel "different" or "abnormal." I did not feel like my everyday reality was "too heavy" or "too personal" to be shared. It was simply life, and almost everyone there understood.

The environment created at HealtheVoices highlighted a crucial truth: the world can accommodate people living with chronic illness, but spaces simply choose not to. The conference gathered people with vastly different conditions and needs, and yet everyone I met felt included and supported. This was not magic. This was intention. This was care. This was a commitment to treating people with chronic illness as fully human. I felt that my needs mattered and that I mattered. The organizers did not treat accommodations as burdens but rather as standard practice. This was eye opening because many institutions act as if inclusion is too much work, but this conference proved that it is entirely possible. In fact, it showed me that inclusion is completely achievable when people genuinely want to create it. To put it simply, inclusion is a choice. Dismissing people is also a choice. Institutions, workplaces, and communities can make room for us, but they simply choose not to invest in the effort.

I left the conference with a heart full of gratitude for the connections I made, the stories I heard, the jokes I shared, the insights I gained, and the revitalized sense of identity that I fostered. I left with a deeper understanding of caregiver burden and the emotional landscapes of people living with all types of conditions. I left with the lived experience of how community is essential for healing. I left with a reminder to show up authentically, even in spaces that do not always understand. I left with a deeper commitment to advocate for people with IBD and for people living with chronic illness(es) more broadly. I laughed more than I expected to, and I actually felt real joy. I left with the realization that I often carry emotional burdens for others and take on roles that are not mine to hold, and that realization is going to guide how I move forward in my personal and professional life.

Most of all, I left with a renewed determination to push for environments that truly include people with IBD and other chronic conditions. We deserve to feel normal, included, and valued. We are not abnormal. We are simply made to feel that way by systems that refuse to accommodate us. Anyone can become disabled at any time through illness, accident, age, etc. Anyone can become sick. Anyone can get hurt. Everyone ages (or at least that is the end goal). It is easy to not be concerned about something that does not affect you, but take it from me, it is 100% possible to wake up sick one morning and never be able-bodied again. That is the story of many people with IBD and many people with chronic illnesses. Inclusion matters because disability affects all of us eventually. Anyone can shift into the world that I navigate every day. In turn, inclusion genuinely benefits everyone.

All in all, HealtheVoices reminded me that despite my IBD, I am not alone—I never was. It reminded me that there are some spaces where people like me can feel completely safe, completely understood, and completely ourselves. There are places in the world where people with IBD can feel completely and beautifully at home. Being in such a space where chronic illness and disability is the norm shifted my understanding of what it means to feel "normal." It showed me what true accommodation, accessibility, community, and compassion look like. It showed me what is possible when people choose care over convenience. It proved to me that inclusion is not only possible, but it is deeply worthwhile. I will carry that truth with me and continue advocating for a world that chooses to see us, support us, and welcome us as we are. And for that, I will be forever grateful.

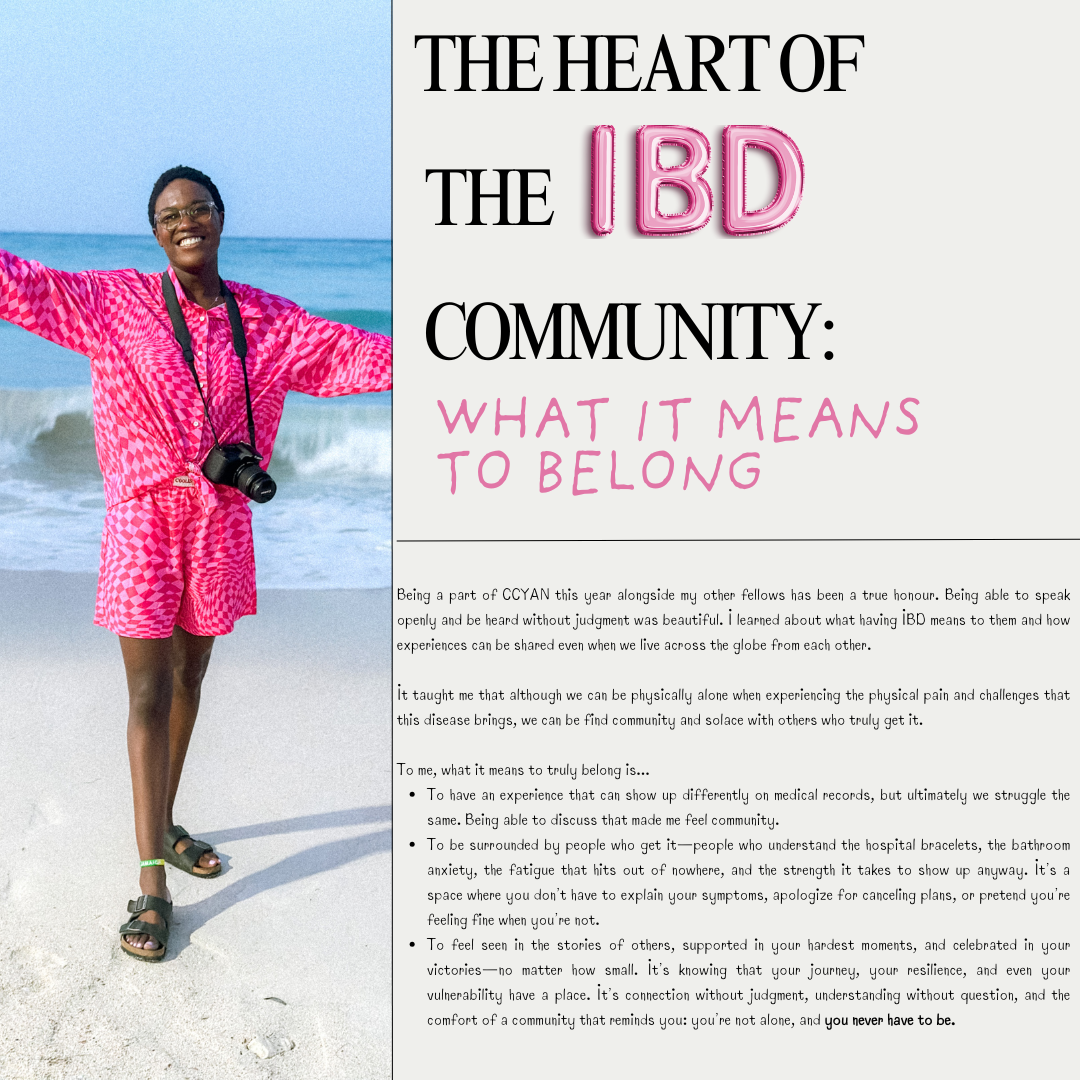

The Heart of the IBD Community: What it Means to Belong

by Lexi Hanson (Missouri, U.S.A.)

Being a part of CCYAN this year alongside my other fellows has been a true honour. Being able to speak openly and be heard without judgment was beautiful. I learned about what having IBD means to them and how experiences can be shared even when we live across the globe from each other.

It taught me that although we can be physically alone when experiencing the physical pain and challenges that this disease brings, we can be find community and solace with others who truly get it.

To me, what it means to truly belong is...

To have an experience that can show up differently on medical records, but ultimately we struggle the same. Being able to discuss that made me feel community.

To be surrounded by people who get it—people who understand the hospital bracelets, the bathroom anxiety, the fatigue that hits out of nowhere, and the strength it takes to show up anyway. It’s a space where you don’t have to explain your symptoms, apologize for canceling plans, or pretend you’re feeling fine when you’re not.

To feel seen in the stories of others, supported in your hardest moments, and celebrated in your victories—no matter how small. It’s knowing that your journey, your resilience, and even your vulnerability have a place. It’s connection without judgment, understanding without question, and the comfort of a community that reminds you: you’re not alone, and you never have to be.

Falsified Empathy in the Workplace: Staying Aware as a Young Adult with Chronic Illness

by Rifa Tusnia Mona (Dhaka, Bangladesh)

As the eldest child, I had the privilege of watching my siblings grow—my brother, six years younger, and my youngest sister, still just a baby. I was there for them whenever my parents were busy, and gradually, without realizing it, I shifted roles. I went from being the one protected on the inner side of the road to being the one who instinctively walked on the outside, protecting others.

By the time I entered university, I felt ready to take on the world. I was driven, ambitious, and full of confidence. It felt like a long-prepared plane finally lifting off the runway—a moment where possibility stretched endlessly ahead.

But just when I thought my life was about to take flight, Crohn’s disease collided with my plans. I barely managed to finish my degree. Before falling ill, I was certain I could secure a job after graduation; I knew my skills and believed they would carry me through. But chronic illness changed that confidence. In my country, remote work often means vulnerability to exploitation, and without my own computer, even that option felt difficult. What frightened me most, however, was burdening my already struggling family with my medical expenses.

There were many moments when I felt my story might end there. I am not someone who easily expresses pain publicly. Yet Crohn’s forced me to ask for help, to depend on others, and in doing so, I discovered something I had never experienced before—what I now call ‘falsified empathy’.

Falsified empathy is empathy that exists only in theory—not in people’s actions. I once worked remotely for a company in Bangladesh. During a month of hospitalization, I unexpectedly received my full salary. But later, HR informed me it was an error and that my next month’s entire salary was deducted because I was unable to work while being hospitalized the previous month. From the next month, I started working remotely and was getting paid half of the salary I got paid while working on site. I raised a complaint, but nothing changed, so I resigned. Company policy required me to work an additional month to ease the transition, which I did— although minimally.

At the end of that month, I went to collect my final month’s payment. The funny part was, when I went to receive the salary, they said that the HR did some wrong calculation and I will still receive some salary from that month! What they didn’t mention was that the amount coincidentally matched the unpaid salary I had earned from my final month of work. In other words, they framed it as an act of understanding and kindness—when in reality, it was merely the payment I was already entitled to. And before leaving, they made sure I signed a non-disclosure agreement.

I share this very personal experience because young people living with chronic illnesses are often vulnerable—and some individuals or organizations may disguise exploitation behind a mask of compassion. They are the “wolves in disguise.” Staying aware and cautious is essential, especially when life puts you in a weakened position.

That’s all from me for this month. Thank you for reading my story. Next month will be my final article of the year, and I promise to bring you something hopeful and uplifting to close the year on a positive note.

Featured photo by Christina & Peter from Pexels.

IBD and Eating Disorders: Control, Fear, and Survival

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

Content Warning: this article discusses eating disorders and topics such as food restriction, binge eating, and body dysmorphia.

For as long as I can remember, food has never been just food. It has been comfort, control, fear, shame, and even the sole measure of my worth. I began struggling with disordered eating as a child, long before I knew anything about Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) or ulcerative colitis—the chronic illness that would later reshape my relationship with my body all over again.

My earliest battle was with anorexia nervosa. I was only around twelve when I began restricting food, counting every calorie, and chasing the illusion of control that came with watching the number on the scale drop. Almost no one knew. The secrecy was part of the sickness—the quiet shame that thrived in silence. It felt safer that way. In a strange way, that shame felt familiar when I was later diagnosed with IBD. Both conditions carried a stigma. Anorexia was whispered about in terms of vanity and control, and conversations about IBD were avoided altogether because they involved the "uncomfortable" topics of bowels, bathrooms, and bodies.

By my senior year of high school, I had relapsed in terms of my anorexia. With prom and graduation approaching, I wanted to "feel confident" in my own skin, but my desire for control quickly turned into obsession again. I convinced myself that going vegan and gluten-free would "clear my acne" and "make me healthier." When it didn't, though, I continued anyway. I continued because I had found something else: the rush of watching the scale drop again. I told myself that it was about health, but deep down, it was about control, perfection, and fear.

When COVID hit, prom and graduation vanished, but my eating disorder didn't. Even though I eventually abandoned the vegan diet, my restriction continued. My hair began falling out in clumps. I was so weak that I needed to be pushed in a wheelchair on family walks and through grocery store aisles. Still, I clung to denial, blaming my fatigue and hair loss on my thyroid. I wasn't ready to admit that I was sick again—not from a medical condition, but from the same mental illness I thought I had conquered.

The human body can only endure starvation for so long before it rebels. Mine did—violently. The pendulum swung from restriction to bingeing. Binge eating disorder involves recurring episodes of eating large amounts of food rapidly, often to the point of physical discomfort, accompanied by feelings of loss of control and guilt afterward.

That was my reality. I gained weight rapidly and felt completely out of control. If anorexia gave me a false sense of control over my life, binge eating disorder stripped it away. I swung from one extreme to another, and both made me miserable. When the weight gain triggered the same familiar self-loathing, I spiraled right back into an anorexia relapse again—a vicious cycle of control and chaos that consumed years of my life.

Eventually, my body began to fail. My heart rate slowed to dangerously low levels. For the first time, I allowed myself to admit the truth: I did not want to die. Recovery, for me, began not with love for my body, but with the simple desire to stay alive.

I began eating again, slowly and carefully. On paper, it looked like recovery—my calories were adequate and my body was functioning. Mentally, though, I was still trapped. I measured every ounce of food, logged every calorie, and spent hours preparing meals to ensure perfect precision. I told myself that it was about maintaining my metabolism, but it was still about fear—the fear of losing control, the fear of gaining weight, and the fear of trusting my body.

Even when I was "eating normally," my life revolved around food. I avoided restaurants unless they posted nutrition information online. I sometimes ordered takeout, only to bring it home and weigh it myself. I had simply traded starvation for obsession. I thought that I had my eating disorder under control, but in truth, it still controlled me.

Around this time, I began experiencing digestive symptoms: constipation, vomiting, reflux, and pain. I now believe that my disordered eating—the pendulum swing from restriction to bingeing, my extremely high insoluble fiber intake in order to eat high volumes of food with the least amount of calories, and my reliance on laxatives due to my food restriction—played a role in triggering my ulcerative colitis, along with the mental/emotional stress caused by it all.

When I was finally diagnosed with IBD, I thought that my disordered eating would take a back seat. I was wrong. Chronic illness can be fertile ground for eating disorders to grow. The constant focus on diet, the fear of flares, and the unpredictability of symptoms can reawaken old patterns of control and restriction.

In the hospital, I was prescribed prednisone and given a list of "safe foods." Back home, I stuck to that list religiously. Underneath it all, though, my old compulsions still resurfaced. I limited not just insoluble fiber, spicy foods, dairy, and alcohol—which are common triggers during flares—but also carbs, sugars, and sodium. This was due to the fear of prednisone-induced weight gain—the water retention, "water weight," or "moon face" that prednisone could cause. I told others that it was about inflammation, but in truth, I was relapsing again—this time under the socially acceptable cover of a "medical diet."

This is one of the hardest truths about eating disorders and IBD: the overlap between medical management and disordered eating behaviors is often blurred. The two can feed each other in quiet, dangerous ways.

IBD can create new patterns of disordered thinking in people who have never struggled with eating disorders before. This is because when your body betrays you like it does with IBD, food becomes (or at least feels like) one of the few things that you actually can control. Plus, when your weight fluctuates rapidly—sometimes losing as much as thirty pounds in a week and then regaining it soon after—it can completely destabilize your sense of self.

For those with body dysmorphia or a history of disordered eating/anorexia, this is especially dangerous. There's no such thing as "small enough" in the mind of someone with an eating disorder. Seeing a "low" number on the scale (even when it's caused by illness) can increase your dopamine and ignite the urge to chase that number, again and again. I remember logically understanding that my low weight during my flare was unhealthy, but emotionally, I still felt anger and panic when the scale went up after treatment. Prednisone's mood swings certainly didn't help with this either—I was at war with both my mind and body.

Now, in remission from IBD, I can finally say that I am also in recovery from my eating disorders. Even so, recovery (like remission) is never as simple as it sounds.

Even in remission, disordered eating behaviors can quietly persist. For many of us with IBD, it shows up as hypervigilance around food: the fear of new foods, the obsession with "safe" meals, or the guilt after eating something "off-plan." It can look like avoiding social events involving food, fixating on weight fluctuations caused by steroids, or tying self-worth to whether symptoms worsen after a meal. These behaviors can masquerade as "caution," but they're often echoes of deeper fear—the fear of pain, the fear of loss of control, and the fear of being sick again.

The parallels between IBD and eating disorders are striking. Both involve an uneasy relationship with the body—a sense that your own physical self has turned against you. Both can make you feel powerless, trapped, ashamed, and isolated. Both can lead to cycles of control and surrender, as well as perfectionism and self-punishment. And both are often invisible to others, hidden behind a mask of composure and "doing fine."

Today, my relationship with food is no longer about control—or at least, I'm trying to keep it that way. I eat intuitively when I can, forgive myself when I can't, and I remind myself that nourishment is not a punishment or reward; it's an act of care. My body has been through battles most people can't see—battles maybe I never even noticed. My body deserves gentleness, not control or being told that it isn't "good enough." Yes, my body may have not been the kindest to me over the years, but I also haven't been the kindest to it in return. While my body may have betrayed me in some ways due to my IBD, it has also gotten me through my IBD, my eating disorders, and so much more. My body is not my enemy. My IBD is not my enemy. My weight is not my enemy. How I look in the mirror one day versus how I look in the mirror the next is not my enemy.

Living with both IBD and a history of eating disorders means constantly walking the line between vigilance and obsession, as well as between self-protection and self-harm. Even so, I've learned that healing is not about never struggling again—it's about recognizing when the struggle starts to whisper and, this time, choosing to listen with compassion instead of control.

For more information on disordered eating & IBD, check out this patient-created resource by the ImproveCareNow Patient Advisory Council.

Image from @jogaway on Unsplash.

Lessons from My Gut

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Yes, I am unique —

my gut became my greatest teacher.

It whispered truths through pain and peace,

showing me the strength in stillness,

the courage in listening,

and the power in being mindful of my body and mind.

I learned to honor,

to protect my quiet spaces,

to find balance between struggle and strength,

between ambition and acceptance,

between the heart’s desires and the body’s needs.

Through pain, I discovered patience.

Through discomfort, I discovered resilience.

Through every challenge, I discovered myself.

Awareness became my guiding light —

a lens through which I saw not just my struggles,

but my strengths, my possibilities, my growth.

It taught me not to blame,

not to expect perfection,

but to understand, accept, and nature.

Now, I walk as an all-rounded soul,

shaped by scars,

strengthened by storms,

yet softened by compassion.

I have learned that life’s lessons are never small;

each one shapes us, molds us,

and pushes us to rise higher than we imagined.

In the CCYAN community, I have found reflection.

Here, voices rise together,

hearts open together,

stories weave together into one shared hope.

We are not alone in our journeys —

our struggles are witnessed, our victories celebrated,

our voices lifted to inspire one another.

My gut has taught me more than pain;

it has taught me presence,

purpose,

patience,

and peace.

It has taught me that even in moments of uncertainty,

even when life feels heavy,

we can remain mindful, balanced, and whole.

And through it all, I continue to grow —

an all-rounded human,

aware, strong, compassionate, and ever-learning.

Photo Credit to: Shutterstock

To See What Cannot Be Seen: Living with Chronic Pain and IBD

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

When most people hear the word "remission," they imagine relief, a clean slate, and the end of suffering. For those of us living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), remission is supposed to mean that we can finally be free of the pain that controlled our lives and simply breathe again. Unfortunately, for so many IBD patients, remission doesn't mean that the pain disappears. Rather, our pain changes form. Our pain becomes quieter, more private, and more invisible. It becomes the kind of pain that can exist in silence. The kind of pain that may not scream for help, yet it still whimpers day and night. The kind of pain that is easy to be overlooked while the rest of the world assumes you're fine.

Chronic pain is one of the most misunderstood aspects of IBD. It lingers long after flares fade, threading through your days in ways that are impossible to explain. It's invisible, yet constant. It's being in pain every single day, but learning to function anyway because you have no other choice. Chronic pain has become a part of my life—like a ringing in my ears that I've had to learn to ignore. I've learned to appear "fine" because visible pain tends to make others uncomfortable, and because I've discovered that admitting the truth often leads to dismissal. I have become so adept at masking my pain that I've become fluent in pretending. Pretending that I'm not silently calculating how much longer I can keep standing before the pain in my abdomen forces me to sit down. Pretending that the subtle grimace that escaped when I moved the wrong way was just a product of my "resting b*tch face." And pretending that "pain" is no longer in my vocabulary.

The pain of IBD patients also commonly goes unrecognized by medical professionals because the traditional 1-10 pain scale was not built for those living with chronic pain. For example, if I tell a doctor that my pain is at a "6/10," they may interpret that as "moderate discomfort." For those without IBD or chronic pain, though, my "6" might be their "10." Our baseline is simply so different from those without chronic illness/chronic pain, therefore making the standard 1-10 pain scale almost meaningless for us. This can have dangerous consequences as pain is typically the body's signal that something is wrong. When we are constantly experiencing pain, it can be difficult to determine whether it's "significant enough" to seek help or whether it's just our "new baseline." The fact of the matter is that any pain should be and is "significant enough," but we've been conditioned to not view it as such. We've been conditioned to accept a new and distorted "baseline level of pain" due to our illness, when those without chronic pain are not encouraged to do the same. Therefore, it can be hard for both us and medical professionals to know when something is "wrong," creating the potential for treatment delays, disease progression, prolonged suffering, and—depending on the illness—even fatal consequences.

Living with chronic pain often means learning to downplay your pain. No matter how much pain I'm in, I never rate my pain as a "10." I rarely even rate it as an "8" or a "9" because I know what happens when I do. I've seen "the look." It's that flicker of suspicion that crosses a medical provider's face when you say you're in severe pain, but you don't exactly "look" like it. I have felt the shift in tone when my honesty is mistaken for medication-seeking or when my tears are assumed to be those of ‘crocodiles.’ Because as it has been made quite clear by many medical professionals, if you don't have overwhelmingly visible evidence of your pain, then it must be exaggerated. Or, you must have a mental illness since "it's just anxiety," and "it's all in your head." So, like many others, I minimize my pain. I say that it's a "4" or "5." I'll tell doctors that my pain is manageable, even when it's often very much not.

The stigma of simply wanting relief is one of the cruelest aspects of IBD and chronic pain. The truth is, it's terrifying to need help in a system that might not believe you. IBD also presents unique challenges when it comes to pain management. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually off-limits because they can actually trigger flares. Opioids, while sometimes the only medications strong enough to even touch the pain, are approached with understandable caution due to their risks (i.e. the potential for constipation, dependency, and/or substance use disorder). As a result, we're often left to "cope." We're told to meditate, breathe, use heating pads so often that we burn ourselves, and/or use methods of distraction while our insides feel as though they're literally being twisted inside-out. If we're lucky, we might just get a pamphlet or a link to a video explaining these coping mechanisms. We're essentially almost abandoned by most medical providers as they expect us to endure significant pain without the use of effective pain relief options.

Don't get me wrong, these coping skills can help, but they certainly don't erase our pain. They just make it more bearable. Over time, the constant strain of pushing through the pain can wear down even the strongest person—the person who has "been through it all" and has a "high pain tolerance." Chronic pain doesn't just live in the body. Chronic pain infiltrates the mind and can chip away at one's patience, hope, and even will to keep fighting.

Yet, I understand why providers are cautious when it comes to pain management because I've seen the other side of it too. I currently work at a substance use disorder treatment center as a soon-to-be therapist. I've noticed that many clients' struggles with substances began in the same place: pain. Some struggled with physical pain, some with emotional pain, and many with both. Some clients even suffered from chronic illness(es)/injuries, were told that there was nothing that could be done for their pain, and were never provided with any sort of pain relief by their doctors. Others were prescribed opioids for a while and were then abruptly cut off from them by their medical providers. Much of their substance use history echoes the desperation that many IBD patients have also experienced—the desperation to simply function. The desperation to hold down a job and just get through the day. The desperation to be able to sleep through constant throbbing and aching. The desperation to escape one's pain for "just five minutes." The desperation to just be.

These stories serve as a reminder that pain affects so much more than what meets the eye. That's why it hurts so deeply when our pain is minimized by doctors, friends, family members, partners, and even by ourselves. We tell ourselves that our pain isn't as bad as it feels, while we're quietly counting the minutes until we can lie down. We tell others that we're "fine" because we don't want to be seen as "fragile" or "dramatic." We tell doctors lower numbers on the pain scale so that they'll take us seriously. Many of us would rather suffer quietly than risk being labeled. We learn to mask pain so well that even those closest to us never usually realize the strength it takes for us to just get out of bed.

Masking pain comes at a cost, though. Each time we minimize our pain, we invalidate our own experience. We erase a little bit of our own truth, piece by piece—a small but painful act of self-betrayal that we've been conditioned to commit in order to be believed. Masking pain also isolates us. It makes our struggle invisible, and in doing so, it allows others—including medical professionals—to not be able to see the undeniable pattern of IBD patients with chronic pain.

Pain is not just a symptom. It's a lived experience that profoundly shapes our relationships, our work, our self-worth, our future, and our sense of identity. For example, we might pursue occupations that don't require physical labor, and we might choose living environments that are close to our caregivers/doctors, have bathtubs over showers, and lack staircases. For those of us living with a chronic illness, pain becomes part of who we are—not because we want it to, but because it demands to be acknowledged.

Living with chronic pain and IBD means existing somewhere in a space between endurance and exhaustion. Between being believed and being dismissed. It means learning to hold compassion for yourself, even when the world doesn't. It means carrying an invisible burden that requires extraordinary strength to bear, even though it feels as though you have no strength left to do so. It means showing up—for others, for yourself, and for life itself—often without anyone realizing just how much effort it all takes.

That quiet persistence is something that I have come to admire deeply, both in myself and in others who live this reality. Because even when our pain is invisible, our resilience is not. It serves as a powerful testament to every person who keeps going despite their own body making the simplest things feel impossible. And even though our pain may be a part of who we are, our resiliency proves that it is certainly not all of who we are. We are so much more than our pain and our illness.

Still, our pain deserves to be acknowledged. Our stories deserve to be believed. Our healthcare system must learn to see what cannot be seen—not to just treat the illness, but to honor the full human experience of actually living with it.

Therefore, we need a better way to talk about chronic pain, especially in regards to IBD. We need providers to understand that our "normal" is not their "normal." That just because we appear to be "fine" does not mean that we are not suffering. That pain in remission is real. And that asking for pain relief isn't manipulation—it's survival.

Living with chronic pain and IBD means learning to navigate a world that often doubts what it can't see. But we exist, and our pain is valid. It's time for the system and the world to finally see us because if you look hard enough, you'll see that our pain is actually not as invisible as it seems—it just continues to go unseen.

Image by @gnikomedi on Unsplash.

Reflections on Curating the “Familial Patterns” Art Show

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

If you haven't already, you can watch a video tour of Kaitlyn’s “Familial Patterns: Generations of Patients” art show here!

Acknowledgements: My warmest thanks to Shelly Philips - my co-conspirator for the show, to Deborah Reid and Tracy Hayes who run Gallery RAG, CCYAN alum Selan Lee for helping me find my message, and to all the CCYAN members and chronically ill creatives who submitted work! This was my first time curating a show and I'm so thankful I had that opportunity!

Since the start of my CCYAN fellowship, I wanted to make an art show highlighting people's shared experiences with chronic illness. In July, I went to Gloucester with a goal and a promised gallery space – while I couldn't fully visualize the show until everything was up on the walls, and imagined so many variations of the themes, ultimately focusing the show on family connections to chronic illness made it much more personal.

Shelly and I spent the duration of the show gallery-sitting and having conversations with visitors about the show's theme. As we reflect back on our time at Gallery RAG, Shelly and I have some final thoughts we'd like to share:

The stigma associated with Crohn's, colitis, and other chronic conditions is something rarely seen, let alone talked about openly. Gallery RAG, which stands for Radical Acts of Generosity, was the perfect place for us to launch this exhibition and confront people's preconceived notions of illness. The show was just a drop in the bucket to spread awareness and promote acceptance. It allowed people to come together from isolated communities - even crossing oceans to create connections. One visitor reflected on her husband's chronic illness and his struggle to find motivation to get out of the house. She thought a creative outlet might help him feel seen and accepted. Others also shared stories with us, about different loved ones struggling with their health. Sometimes just showing up is half the battle, making a safe space to create, breaking the cycle of isolation, and talking about taboo topics that are usually swept under the rug. It felt good to normalize our medical issues and talk about them casually with visitors. We hope the gallery guests and livestream viewers were able to connect with the amazing variety of pieces in the show.

Looking into the future, Shelly wants to explore how to reverse the curse of chronic illness by lessening its impact on future generations. She hopes to look into how that in itself could break family cycles of trauma. Shelly wants her future work to shed light on the mothers who never knew that they had undiagnosed autoimmune or inflammatory disease. She plans on investigating how history repeats patterns in the things handed down - after mothers have already passed down the cellular dysfunction - and exploring what immune modulation, environmental changes, and the microbiomes change such patterns. During our conversation, Shelly also talked about Alexis Gomez’s poem about seeing her mom in a different light and how much that touched her. We hope to collaborate more in the future to share the patients’ perspective and focus on how art/writing can be a healing tool.

We loved how the poems and art in the exhibition worked together. Seeing all the different submissions from poetry, collage, zines, prints, paintings really showed there are so many expressive outlets to utilize. It felt larger than us and we are so grateful we had the opportunity to share your stories. We enjoyed the challenge of making the show accessible for everyone - whether international or on the other side of the country and we can't wait to see what our next chapters bring!

If you haven't already, you can watch the video tour of Kaitlyn’s “Familial Patterns: Generations of Patients” art show here. Below, you can also see some of the pieces submitted by CCYAN fellows and other community members!

Beamlak Alebel’s (CCYAN Fellow, Ethiopia) poem, “A Heart That Heals,” thanked all the doctors, nurses, surgeons, family, and friends for helping her on her journey to healing. Her heartfelt gratitude shined through to readers who shared their appreciation for their own support systems.

Aiswarya Asok’s (CCYAN Fellow, India) poem, “Mosaics.” tackled the grief and emotions attached to carrying her mother’s hidden pain. Aiswarya’s piece offered a glimmer of hope, in that through our endurance and shared suffering, we might find more answers and a better prognosis to bring about change.

Alexis Gomez’s (CCYAN Fellow, USA) poem, “Letter to Mom,” also reflected on her relationship with her mother and how similar yet different their medical journeys are from one another. Her writing felt like a sincere attempt to grapple with mixed emotions, her mother’s guilt, and their shared perseverance in the face of IBD.

Multiple works from artist Andreana Rosnik, including: “Recipes for a Flare,” a collage communicating the danger and inflammation that comfort foods might cost us internally, which took me back to my own fights with food. “Portrait of the Artist as a Colon,” a zine (a small art booklet) illustrating her challenges living with Ulcerative Colitis. As an artist who also draws colons, I appreciated Andreana’s refreshing take on a digestive system fraught with issues. Her “colon wyrm” and “biblically-accurate intestines” deserve a spotlight as well, and could easily be made into merch and tshirts for other folks with colon issues.

Nancy Hart’s acrylic painting, “COW,” (top right) depicted a pink cow silhouette on a black and white backdrop to represent one of her many inherited allergies. Marnie Blair’s print, “Snakes and Rivers,” (center) echoed ideas of transformation and survival on the surface of a blue disposable medical drape. The layers of meaning and the subtle ties to both the body and environment appealed to us as we were curating the show.

See the rest of the featured artwork from Kaitlyn and other CCYAN community members in the video tour!