NEWS

Re-discovering Myself

by Aiswarya Asokan (South India)

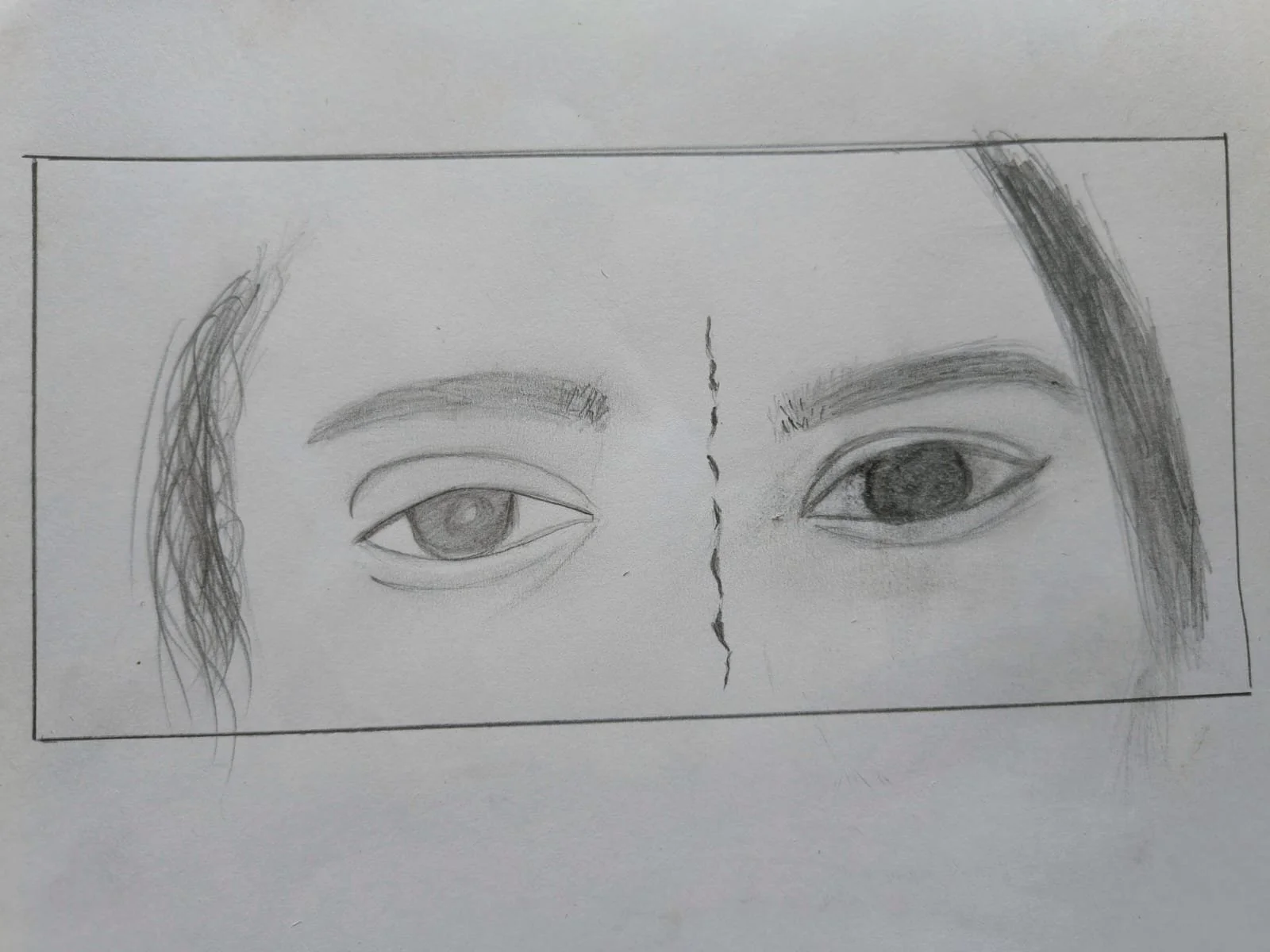

About the artwork:

The eye on the left hand represents depression, pain, withdrawal and hopelessness, while the one on the right-hand side represents fire, aggression, hunger, frustration, control and the drive for action. The broken line in the middle represents a surgical scar, which remains a symbol of the cost paid by the body for balancing the clash of emotions. The body as a whole is trying hard to hold it all together, to find the balance for emotional stability, for safety, for peace, for happiness. It is looking out for compassion, it is looking for love. And the only way to get to know what it is looking for is to look inward.

Reflections on Curating the “Familial Patterns” Art Show

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

If you haven't already, you can watch a video tour of Kaitlyn’s “Familial Patterns: Generations of Patients” art show here!

Acknowledgements: My warmest thanks to Shelly Philips - my co-conspirator for the show, to Deborah Reid and Tracy Hayes who run Gallery RAG, CCYAN alum Selan Lee for helping me find my message, and to all the CCYAN members and chronically ill creatives who submitted work! This was my first time curating a show and I'm so thankful I had that opportunity!

Since the start of my CCYAN fellowship, I wanted to make an art show highlighting people's shared experiences with chronic illness. In July, I went to Gloucester with a goal and a promised gallery space – while I couldn't fully visualize the show until everything was up on the walls, and imagined so many variations of the themes, ultimately focusing the show on family connections to chronic illness made it much more personal.

Shelly and I spent the duration of the show gallery-sitting and having conversations with visitors about the show's theme. As we reflect back on our time at Gallery RAG, Shelly and I have some final thoughts we'd like to share:

The stigma associated with Crohn's, colitis, and other chronic conditions is something rarely seen, let alone talked about openly. Gallery RAG, which stands for Radical Acts of Generosity, was the perfect place for us to launch this exhibition and confront people's preconceived notions of illness. The show was just a drop in the bucket to spread awareness and promote acceptance. It allowed people to come together from isolated communities - even crossing oceans to create connections. One visitor reflected on her husband's chronic illness and his struggle to find motivation to get out of the house. She thought a creative outlet might help him feel seen and accepted. Others also shared stories with us, about different loved ones struggling with their health. Sometimes just showing up is half the battle, making a safe space to create, breaking the cycle of isolation, and talking about taboo topics that are usually swept under the rug. It felt good to normalize our medical issues and talk about them casually with visitors. We hope the gallery guests and livestream viewers were able to connect with the amazing variety of pieces in the show.

Looking into the future, Shelly wants to explore how to reverse the curse of chronic illness by lessening its impact on future generations. She hopes to look into how that in itself could break family cycles of trauma. Shelly wants her future work to shed light on the mothers who never knew that they had undiagnosed autoimmune or inflammatory disease. She plans on investigating how history repeats patterns in the things handed down - after mothers have already passed down the cellular dysfunction - and exploring what immune modulation, environmental changes, and the microbiomes change such patterns. During our conversation, Shelly also talked about Alexis Gomez’s poem about seeing her mom in a different light and how much that touched her. We hope to collaborate more in the future to share the patients’ perspective and focus on how art/writing can be a healing tool.

We loved how the poems and art in the exhibition worked together. Seeing all the different submissions from poetry, collage, zines, prints, paintings really showed there are so many expressive outlets to utilize. It felt larger than us and we are so grateful we had the opportunity to share your stories. We enjoyed the challenge of making the show accessible for everyone - whether international or on the other side of the country and we can't wait to see what our next chapters bring!

If you haven't already, you can watch the video tour of Kaitlyn’s “Familial Patterns: Generations of Patients” art show here. Below, you can also see some of the pieces submitted by CCYAN fellows and other community members!

Beamlak Alebel’s (CCYAN Fellow, Ethiopia) poem, “A Heart That Heals,” thanked all the doctors, nurses, surgeons, family, and friends for helping her on her journey to healing. Her heartfelt gratitude shined through to readers who shared their appreciation for their own support systems.

Aiswarya Asok’s (CCYAN Fellow, India) poem, “Mosaics.” tackled the grief and emotions attached to carrying her mother’s hidden pain. Aiswarya’s piece offered a glimmer of hope, in that through our endurance and shared suffering, we might find more answers and a better prognosis to bring about change.

Alexis Gomez’s (CCYAN Fellow, USA) poem, “Letter to Mom,” also reflected on her relationship with her mother and how similar yet different their medical journeys are from one another. Her writing felt like a sincere attempt to grapple with mixed emotions, her mother’s guilt, and their shared perseverance in the face of IBD.

Multiple works from artist Andreana Rosnik, including: “Recipes for a Flare,” a collage communicating the danger and inflammation that comfort foods might cost us internally, which took me back to my own fights with food. “Portrait of the Artist as a Colon,” a zine (a small art booklet) illustrating her challenges living with Ulcerative Colitis. As an artist who also draws colons, I appreciated Andreana’s refreshing take on a digestive system fraught with issues. Her “colon wyrm” and “biblically-accurate intestines” deserve a spotlight as well, and could easily be made into merch and tshirts for other folks with colon issues.

Nancy Hart’s acrylic painting, “COW,” (top right) depicted a pink cow silhouette on a black and white backdrop to represent one of her many inherited allergies. Marnie Blair’s print, “Snakes and Rivers,” (center) echoed ideas of transformation and survival on the surface of a blue disposable medical drape. The layers of meaning and the subtle ties to both the body and environment appealed to us as we were curating the show.

See the rest of the featured artwork from Kaitlyn and other CCYAN community members in the video tour!

Michelle’s IBD “Burn Book”

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

Inspired by Mean Girls and high school yearbooks, I created an “IBD Burn Book” to shed light on the invisibility of IBD and emphasize the importance of empathy when interacting with someone with IBD.

When you first open the Burn Book, you’ll see that my “Mask” has been crowned Prom Queen. The images on this page are from moments when I had my mask on—when I pretended to be “fine.” The background words reflect how others perceive me more positively when I wear this mask, which is why it was elected Prom Queen.

The next page is a Student Feature of my Inner Thoughts. Here, I am without my mask. This contrast serves as a reminder that appearances can be deceiving—what you see on the outside isn’t always real; it might just be a mask.

Following that is a Not Hot List, which consists of a collection of phrases people should never say to someone with IBD. (Sadly, every one of these remarks has been said to me).

The final page of the Burn Book is a WANTED poster—for empathy. Instead of harmful comments, this page lists empathetic phrases one should say to someone with IBD. Essentially, it serves as the “Hot List” in Mean Girls or high school terminology.

———

Invisible illnesses come with their own set of challenges—such as a widespread lack of awareness—but the focus here is how easily someone with IBD can hide their struggles. Smiling through the pain, pretending to feel well—it becomes second nature. I’m not the first person to wear a “mask” to feel accepted or to make others comfortable, and I certainly won’t be the last.

The reality, though, is that IBD is a constant battle. Even if you see me dancing with friends, traveling, or enjoying a big meal, I am still struggling. The takeaway? You never truly know what someone else is going through, so always choose kindness. More importantly, choose empathy. If you do know what someone is going through (specifically IBD in this case), be especially mindful of your words and actions. While you might assume your words and actions don’t affect us, remember—we’ve had a lot of practice hiding our pain.

“I think but dare not speak.” - The hidden misconceptions of chronic illness.

By Selan Lee from the United Kingdom

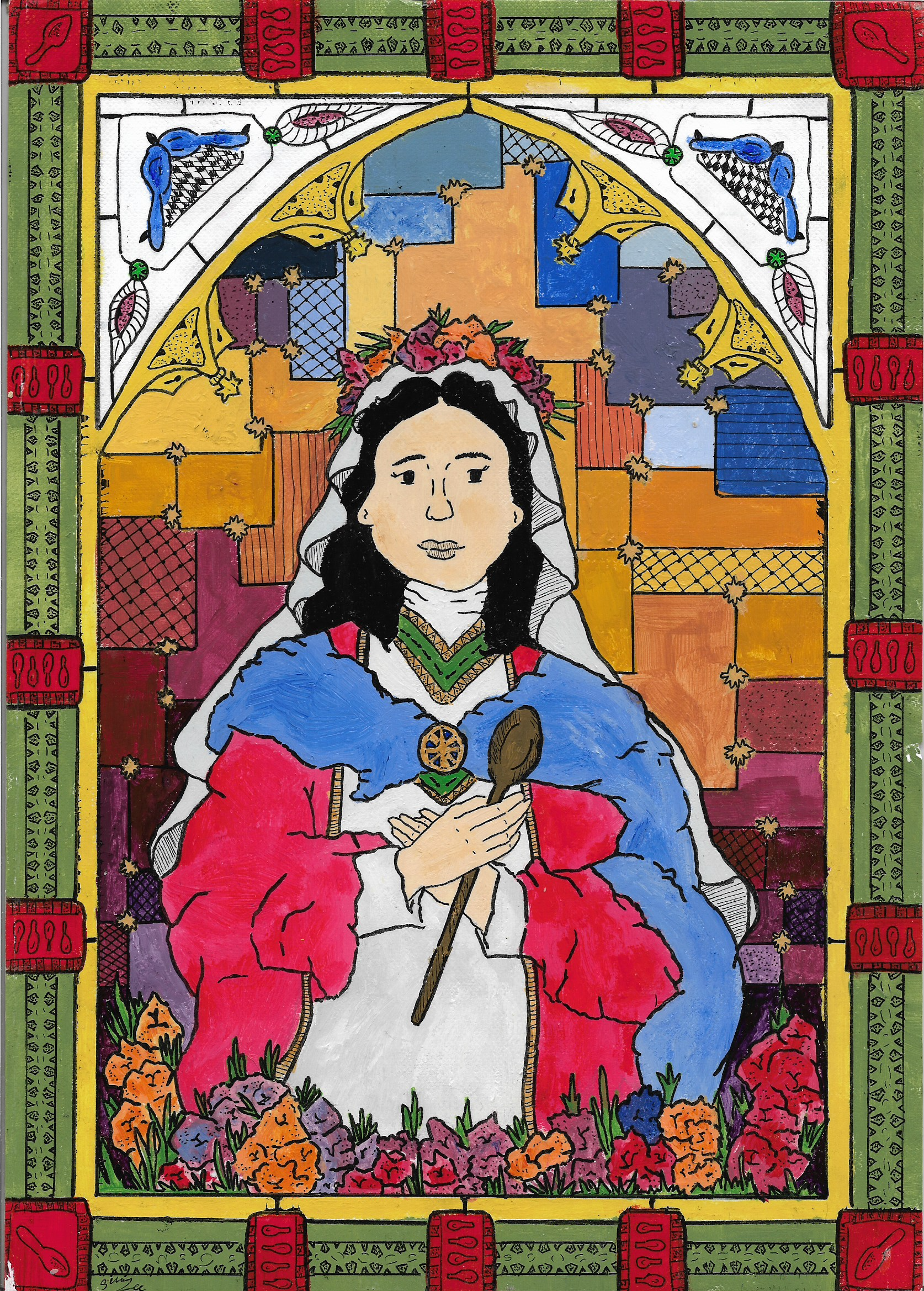

I interned in the Perspectives Programme at Kaleidoscope Health and Care during my placement year. During this internship, I designed and managed client events and workshops, created weekly progress reports, and learned about healthcare systems and policy (in the UK, at least). But most importantly, I designed, curated and hosted an art exhibition celebrating intersectionality in chronic illness entitled ‘Low on Spoons, Not Identity’. Among the fabulous photography, fantastic comic illustration and fanciful jewellery pieces on display was a set of 3 (very amateur) A4 panels by me. Entitled “I am not…” each panel addressed a misconception often thought of but not spoken about chronic illness (some of which many in the chronic illness community still believe or are associated with by society, our loved ones or even ourselves.)

The first panel focused on the sainthood or idolisation of the chronically ill. Now, it may seem strange to find inspiration or guidance from someone who is often house- or hospital-bound and barely has enough energy to perform miracles - but the sick have been canonised as martyrs or lauded as idols for years. For example, fictional characters such as Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol and Beth in Little Women are seen to be too good for this world. Katie Hogben remarks in her exhibition ‘Breaking Apart the Sick Girl Trope’ - that Beth is a “happy flower girl… Her amenable nature never falters, even in her long-term suffering and eventual death.”[1] In modern times, the misconception prevails - so much of the media surrounding chronic illness showcases a beautiful, rose-tinted, inspirational view of life with an often draining and limiting condition. The only way you can tell Hazel in The Fault in Our Stars has cancer is because she has a nasal cannula and an oxygen tank with her—no sign of fatigue, weight loss or steroid-induced moon face. Our social media is also filled with inspirational chronic illness stories and comments praising our ‘bravery’. I’ve received comments which praise ‘my dedication’ for studying during my infusions when really there’s no choice otherwise.

Such aesthetically pleasing and morally affirming portrayals of chronic illness omit the less beautiful aspects of chronic illness. Consequently, this omits many realities and negates the ability of people with long-term conditions to voice the negativity in their situation. The misconception of being akin to a saint may be desired, but it enforces toxic positivity on the chronically ill - the individual must maintain a positive attitude and minimise their struggles; their lives are not validated if they do not meet this ideal. I, too, play my part in perpetuating this image. I have made social media posts highlighting my achievements since my diagnosis, but rarely do I post about the days I shut myself away in my room when I’m too exhausted. I don’t tell friends about the time I cried about my situation in an accessible toilet in a train station, but rather about the perks of having a RADAR key. Many of us fear isolation and lack of empathy by sharing the ugly side of chronic illness. Still, by continuing this misconception, we are abetting it, and its existence will remain ingrained in its stained glass iconography - distorting our authentic lives.

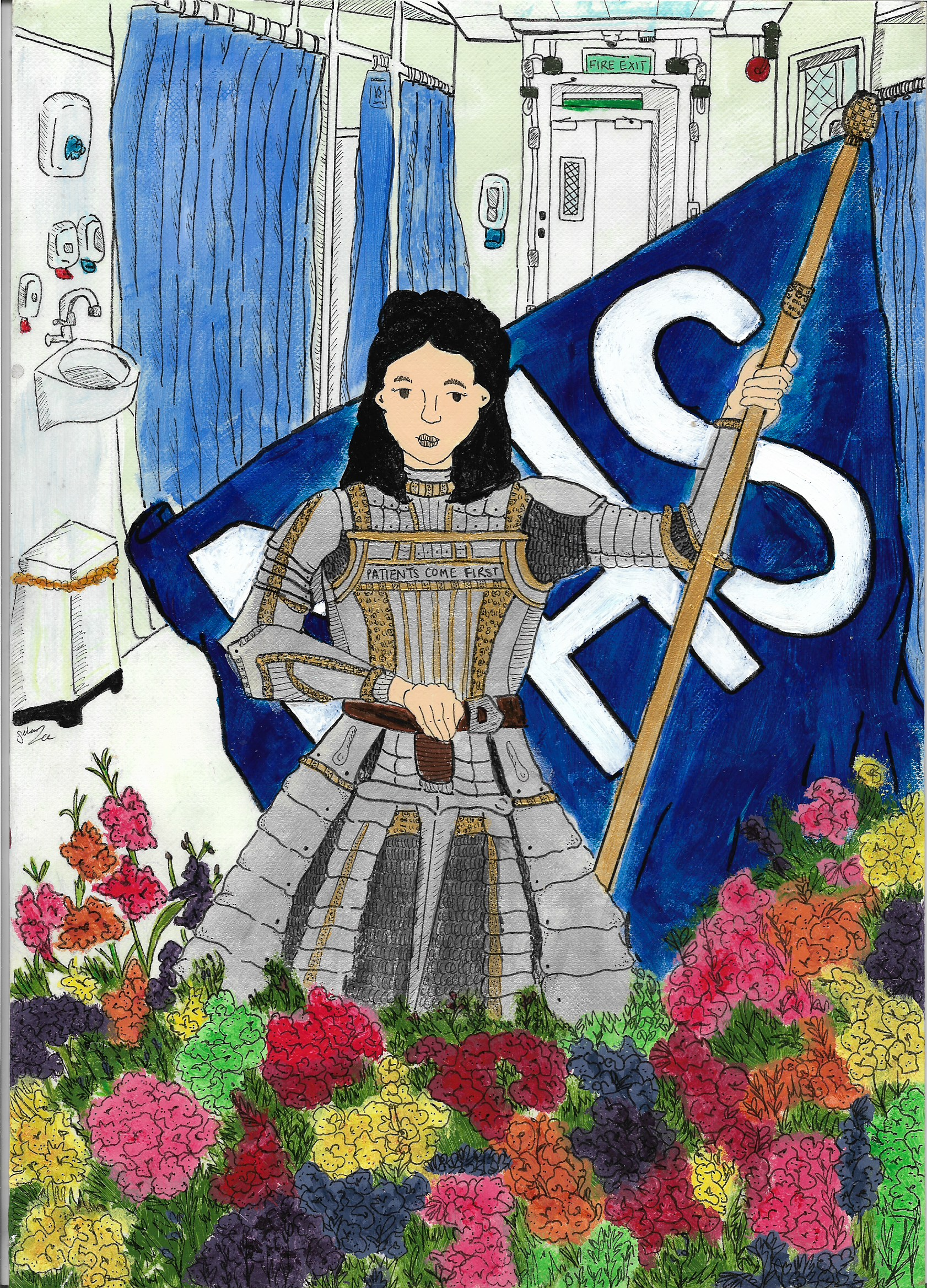

The second panel confronted the depiction of journeys in chronic illness as a ‘battle’ and the chronically ill individual as a ‘warrior’. I’m sure many people with chronic illness have encountered button badges, hoodies and posters emblazoned with the phrase ‘chronic illness warrior’. Or you probably have seen quotes that link your day-to-day existence with chronic illness as a ‘fight’ or ‘daily battle’, and by living, you are ‘winning’ or ‘not backing down’. These phrases can be supportive, but only temporarily. Chronic illness is something you can never win - hence the use of chronic. Being a warrior means you are courageous, like Joan of Arc (a figure I drew inspiration from in the panel), but I don’t think I am. None of my choices in my health journey are necessarily brave. I chose to self-inject my second biologic because the first stopped working, and I wanted to reduce the time spent in the hospital. I had surgery for my fistula because the pain was unbearable. None of these actions fit the definition of brave. The Cambridge Dictionary defines bravery as “showing no fear of dangerous or difficult things”.[2] I dealt with my dangerous or difficult things, the risk of a flare, anaphylaxis and infection, with plenty of fear. To live my life to its fullest possible extent, I have to accept hard-to-swallow realities and understand that when my life is on the line - I have no choice otherwise. Realising you have no choice is terrifying, but it is equally terrifying knowing the word brave is used here as a stand-in for ‘I’m glad it’s not me’. You’re right - you should be glad it’s not you, but like with the inspiration misconception, the use of ‘warrior’ and ‘courageous’ minimises our lives and makes our entire existence seem pitiable. Our existence is the same as yours - human.

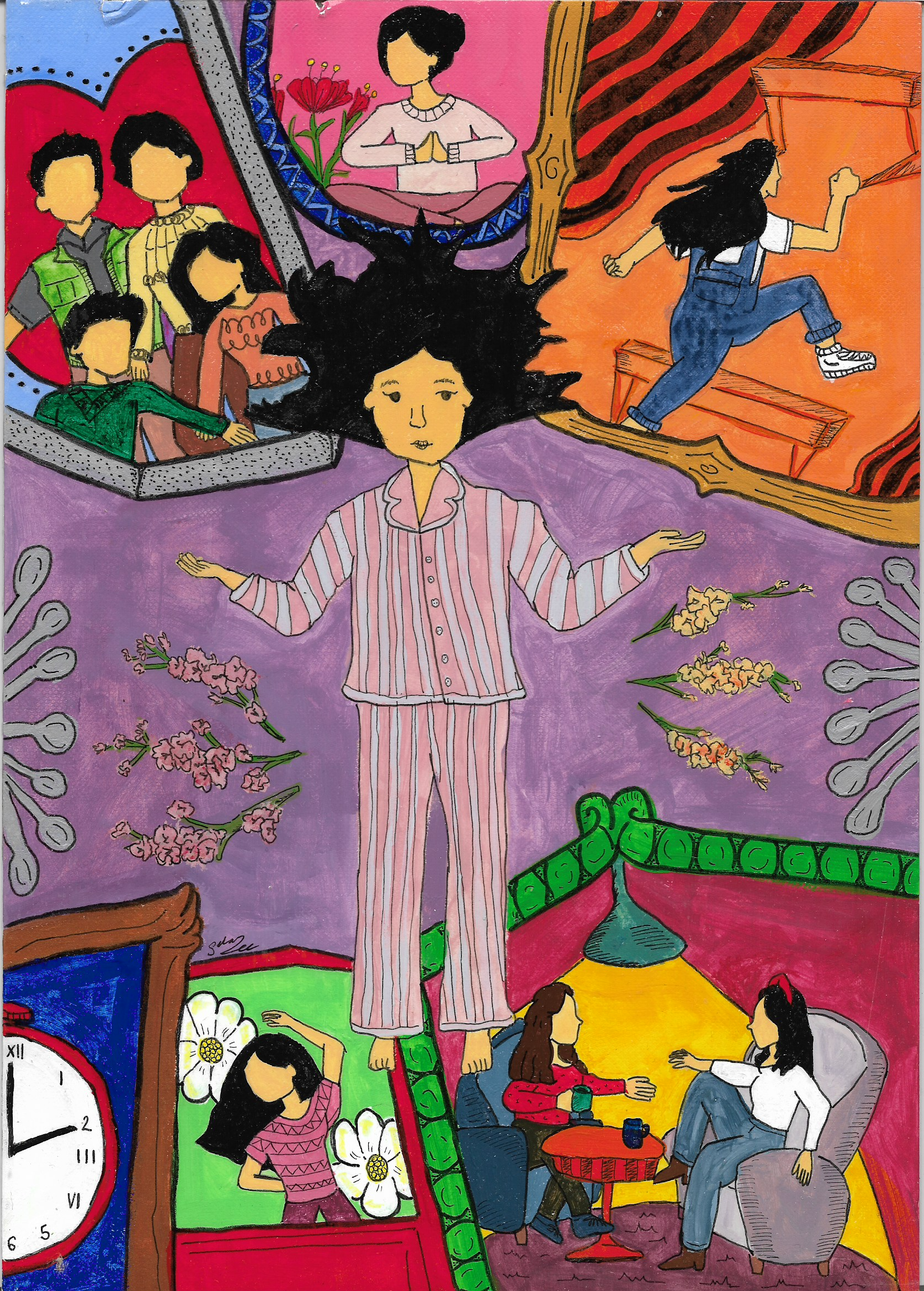

Finally, the last panel looked at the misconception of chronically ill people being lazy. I’m sure plenty have felt lazy and wanted to ‘rot’ away in bed for the day, but the fatigue many chronically ill people suffer from is never the same. In early 2022, the term ‘goblin mode’ began trending, and many embraced an aesthetic which encouraged unapologetic laziness and self-indulgence. However, the aesthetic, as highlighted by Hannah Turner, ignores how much of the disabled and chronic illness community “embody goblin mode because there is often no choice not to”.[3] When you have low energy, you don’t want to expend the few spoons you have to change clothes or wash your hair. You use them to feed yourself or conserve that energy.

Moreover, laziness has connotations of purposeful slovenliness. I doubt anyone wants to be restricted to their homes while their friends go out or we miss out on cultural experiences. I missed my first concert, didn’t get to spend the last few months of high school with my friends, and had to cancel at the last minute for so many things because of my fatigue. My ‘laziness’ is a harbinger of regret over every missed opportunity. None of this is purposeful. I do not want to be ‘lazy’, but laziness has been thrust upon me.

There are many misconceptions out there about chronic illness, and there are probably some I don’t know of. But by keeping them unspoken and allowing them to penetrate our thoughts - we are enabling their pervasive influence on how we tackle chronic illness. Letting them be spoken and discussed will allow us to change the perspective and reduce their potency - one misconception at a time.

References

Brave. (2024). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/brave

Turner, H., & Sacca, P. B. B. (2022, March 21). As A Disabled Woman, The Goblin Mode Trend Doesn’t Sit Right With Me. Refinery29. https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/goblin-mode

Welcome to Breaking Apart the Sick Girl Trope online exhibition. (2022, November 1). Breaking Apart the Sick Girl Trope. https://thesickgirltrope.wordpress.com/online-exhibition/

Constructing a Visual Language in the Chronic Illness Community

By Ibrahim Z. Konaté (U.S.A. and France)

Featured photo by JULIO NERY from Pexels

Learning at the age of 23 that I have a life-long disease was incredibly destabilizing. Once my care team developed a treatment plan that allowed me to regain some normalcy, I felt that I was still struggling to find my footing in this new reality.

The power of receiving my diagnosis lay in finally having the vocabulary to explain to others what I was experiencing, but I was still left without the tools to process this journey for myself.

I turned to my care team and was introduced to resilience, coping, acceptance, and many other important post-diagnosis concepts. Though I was able to receive guidance on these tools and worked to incorporate them into my life, I felt like I was missing something. As these words started piling up, it became harder for me to grasp their meaning.

The more I read about these words, the greater the chasm between myself and these concepts grew. I was meant to apply these ideas to my life but felt incapable of seeing them as anything beyond research frameworks.

I needed a way to animate these notions to see how I could fit them into my daily life. As a visually-oriented person, my first reaction was to see what imagery was already associated with these terms. When I put these words into Google Images, I was confronted with drawings of flowers growing through cracks in the sidewalk and stock photos of mountain hikes. Though these images got the basic point across, I was seeking something that could translate these ideas from words on a page to relatable human experiences and emotions.

For inspiration, I took a trip to the Brooklyn Museum and saw an exhibit entitled The Slipstream: Reflection, Resilience, and Resistance in the Art of Our Time. This collection showcases the work of intergenerational, BIPOC artists to “hold space for individuals to find their feelings of fear, grief, vulnerability, anger, isolation, and despair—as well as joy, determination, and love—reflected in art.” Though this exhibit was curated in response to the global pandemic and social events of 2020, I recognized my own struggles in the featured artwork. My favorite part of the exhibit was a room dedicated to centering pleasure to cope with and overcome conflict.

This is black text written on a white wall. At the top of the image is the word “Pleasure.” Below this image is a paragraph of text that reads: “In tumultuous times, experiences of joy, humor, leisure, and rest can hold radical possibilities for transformation. These artists capture moments of everyday pleasure, be they located in family, friendship, and community, in life’s daily rituals, or in creativity and the act of art-making itself.”

I started to wonder - if I could place any piece of art in this room to represent my experience as a Crohn’s Disease patient, what would I choose?

I spent the next week searching through digital archives to find an image that not only would embody my journey thus far but would also remind me of how developing resilience would help me keep moving forward. Finally, I found the perfect image, bought a poster of it, and hung it up on my wall. Now, the first thing that I see when I get up in the morning is a picture taken by Malian photographer, Malick Sidibé, entitled Nuit de Noël.

This photograph was taken in the early 1960s after the liberation of most West African countries from colonial rule. I think about the insecurity that was experienced by many people, including my parents, during this time of transition. When I see this picture, I remember how my family taught me that even in uncertainty one can still smile, dance, and hope that the future brings better days.

A square picture frame with black borders hangs on a white wall. The image in the frame is a black and white photograph showing a man and a woman dressed in light clothing dancing at night in a courtyard. Below the framed image are 5 sunflowers.

Words are important, but sometimes they are not enough. To conceptualize the abstract notions of resilience and acceptance, I needed to find imagery that could help me envision these concepts in my life. My belief is that there is something incredibly universal that can be found in our subjective experiences. I want us to create a new visual language to describe our journeys in this community. My hope is that we can replace the stock photos we find when we search for images related to resilience with artwork or even our own pictures. So I ask, what images describe your story?

This article is sponsored by IBDStrong.

IBD Strong is a volunteer grassroots organization that provides a community of hope, connection, inspiration and empowerment to children, teens and families living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. They believe that every individual diagnosed with IBD deserves hope and opportunities to thrive. IBD Strong’s mission is to inspire and empower individuals living with IBD to not let the disease define them.