NEWS

HealtheVoices 2025: Feeling Beautifully at Home with my IBD

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

Disclaimer from Michelle: Johnson & Johnson paid for my travel expenses to attend HealtheVoices, but all thoughts and opinions expressed here are my own. This conference was not attended as a part of the CCYAN fellowship.

From November 6th through November 9th, 2025, I stepped into a space that I had never experienced before. HealtheVoices 2025 was more than a conference for advocates like me. HealtheVoices became a place where my body, story, and heart finally felt understood. I walked in as an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and mental health advocate, but I walked out feeling like I had reclaimed parts of myself that IBD had slowly worn down.

IBD affects so much more than the digestive system. My life is shaped by symptoms that are unpredictable and exhausting, with my mental health experiences running parallel to this journey and adding additional weight. IBD ultimately shapes the way that I move through the world, my energy, my confidence, and even the level of honesty that I bring to conversations. Daily life can feel even more heavy and lonely because it is rare for me to be in a room filled with people who truly understand what chronic illness feels like, and vulnerability about illness does not always land well with people who cannot relate. At HealtheVoices, that weight softened the very moment that I arrived. The environment made me feel safe before I even realized that I had been holding my breath for so long.

I met people living with many types of chronic conditions, from visible disabilities to more silent illnesses like mine. I met caregivers who understood illness from the position of love and exhaustion. I met people who shared my diagnosis of IBD and people who shared my mental health struggles as well. In turn, I finally did not feel like the odd one out or like the only person in the room fighting a battle that no one else could see. For one weekend, I felt truly seen, understood, and supported. It felt like everyone there spoke a language that I always knew but rarely had spoken back to me. It was a rare and profound reminder that community, safety, and understanding can change the way a chronically ill body feels because, to put it simply, I finally felt normal.

While I cannot speak for all of the attendees, I know that I felt this way for a variety of reasons, and I am going to try my best to put it into words.

For starters, I could tell that the conference itself was intentionally designed with us in mind, and that intention showed in every detail. Organizers checked-in on us often, encouraged rest, and made it clear that nothing was mandatory. They understood that rest is both a need and a responsibility. They understood that pushing too hard could cause flare ups, particularly for those of us with IBD or conditions that involve fatigue, pain, and unpredictable symptoms. Even travel was supported as I received reminders and check-ins to make sure that I made it to my flight safely. This took the emotional labor out of the small things that usually drain me, and their help and accommodations were never made to feel like favors. Plus, everything was optional, yet everything was thoughtfully provided. It was all offered with genuine care, and that is something that I rarely feel in spaces outside the chronic illness community. I truly felt taken care of at every moment. I never felt pressured to show up to an event, and I never felt like a burden or a "waste of an attendee" if I did not. I felt valued simply because of who I am, IBD and all. Typically, I am made to feel as though my IBD devalues me throughout many domains of life, but I felt the opposite way while at HealtheVoices. I also felt considered and looked out for without being pitied or restricted. In other words, I felt empowered to take care of myself and to be the advocate I want to be, while also realizing that there is power in accepting help and care—there is the "power of us."

Regarding this "power of us," I was able to witness and experience how chronic illness can foster unity, even when diagnoses and symptoms may differ. This was exhibited right off-the-bat at the very first dinner of the conference when attendees were grouped based on their health condition, and I accidentally sat with the mental health and pulmonary hypertension group instead of the immunology group. What started as an awkward mistake due to my brain fog after a long day of traveling ended up turning into a gift. At this dinner, I connected with people who understood my mental health story in ways that felt grounding and familiar. Some even worked in the mental health field like I do, which felt incredibly validating. Therefore, even though not a single individual there had IBD, our emotional landscapes were still strikingly similar. We each shared our stories of career challenges, burnout, medical dismissal, discrimination, chronic pain, hospital admissions, fatigue, chosen family, the exhaustion of being misunderstood, and the emotional toll of navigating life and relationships with an unpredictable body and/or mind. We also connected over experiences specific to gender, such as being dismissed in medical settings until a male caregiver shows up.

These discussions reminded me that chronic illness is not defined only by biology. It is shaped by stigma, gender, identity, socioeconomic realities, and the emotional toll of constantly having to justify our experiences. Even people whose conditions had nothing in common with mine understood the same nuances of fatigue, pain, fear, and perseverance. Our hearts carried extremely similar stories, and the overlap was both comforting and heart-wrenching at the same time.

After that realization, I made a conscious effort for the rest of the weekend to approach people without looking at their badges. I did not want to lead with diagnoses anymore since I understood that a diagnosis was not the only thing that could foster deep connections. I wanted to understand people for who they were rather than for what condition they advocated for, even though I understood that advocacy often played a large role in the attendees' identities.

Despite it being an advocacy conference, my goal was not to advocate or educate that weekend. I simply wanted honest connection. I wanted to feel safe being myself. I wanted to meet people who would understand both the heaviness and the humor that come with living in a body that needs extra care and requires constant negotiation, without limiting myself by my diagnosis. My IBD has limited me enough already, and I was not going to let it stop me from making the meaningful connections that I have been seeking just because of a label. As it is, living with IBD and mental health challenges is incredibly isolating, especially when daily experiences and honesty are treated as oversharing. Everyone, including myself, preaches vulnerability, but it is difficult to be vulnerable when people do not know how to respond or cannot relate to your daily reality. That is why having the space to openly share about your day-to-day life—without the sugarcoating—is essential, and I found that space with each and every attendee carrying all of the diagnoses under the sun. It did not matter if they had IBD, a different chronic illness, or if they were a caregiver since we could all relate to one another in some way.

This was an incredible phenomenon that attendees and I noticed since at HealtheVoices, we did not have to explain the basics. Each conversation started with an innate understanding of one another. This understanding was not just based in compassion and shared experiences as it was oftentimes also based in shared medical knowledge/terminology, tips and tricks for navigating the healthcare system, etc. This is because everyone there lived some version of the same complexity. For example, many of the attendees understood Prednisone's mental and emotional side effects, sometimes even making light of it nonchalantly during conversations. Outside of the chronic illness space, these jokes and statements would have to be explained or given some background information, which can become exhausting over time, especially as you meet more people throughout your life. Having people who just "get" certain things—without needing to pause the conversation to explain and without having to worry about how it might be taken—is a breath of fresh air.

I did not have to soften the truth or worry about being labeled as "dramatic" or "negative." I did not have to explain why I left an event early or arrived late, nor did I have to explain why I did not finish the food on my plate. People just got it. This conference felt like a safe haven where I did not have to justify my needs or my existence as someone living with IBD. Even when we were not familiar with aspects of each other's health condition(s), we approached one another with curiosity rather than making assumptions, offering unsolicited medical advice or "natural remedies" that we have likely already tried/been advised to try countless times, or making remarks along the lines of, "everything happens for a reason" and "at least it's not cancer."

Conversations were honest but never forced, and I found that our weekend did not revolve entirely around illness. Sure, we cried a lot, but we also laughed a lot. We talked about hobbies, goals, spirituality, tarot, and things that were not centered in our diagnoses. It felt balanced in a way that my everyday life rarely does since either my whole world feels tied to my IBD, or I attempt to live in denial of its existence. At HealtheVoices, I did not have to shrink or edit my truth.

Yet, there was a moment very early into the weekend when I felt myself growing emotionally tired. While there were those intriguing conversations outside of chronic illness, most conversations were still deep and personal in nature. As a result, I felt an unexpected countertransference building inside of me, as if I had automatically tried to become the "listener" and "helper." Hearing such heavy stories that mirrored my own felt draining at first because I empathized deeply, and I wanted to hold people's burdens for them for as long as I could. That is what I am used to doing for others, and that is what I honestly enjoy doing. I see it as a privilege to be trusted with such personal information and stories of deep pain. Thus, I wanted to show my gratitude for this privilege, which expressed itself as me unconsciously attempting to relieve some of their burdens. It was as if I had naturally tried to step into the role of "therapist" instead of simply being myself. It is a habit that comes naturally to me, especially since I am entering the mental health field as a therapist and hope to work with people who have chronic illnesses.

I also initially experienced some imposter syndrome early into the conference. I was surrounded by these incredible advocates, many of whom have been advocating for decades. Some were even making a career out of their advocacy journeys. Even though it feels like IBD has been a part of my identity for my whole life, I was only diagnosed 4.5 years ago. Similarly, even though I feel as though I have been advocating for years, I really have only been actively advocating and becoming involved in the IBD community this past year. This made me begin to question why I was selected to attend the conference. What the heck do I have to offer? The more this question weighed on me, the more I felt the need to make up for my perceived lack of experience. This translated into my attempt to take on that therapeutic role that is all too comfortable because at least I would be offering something.

After a good night's rest that day, I realized something important: I was not there to fix anything, lighten anyone's burden, or carry emotional weight/pain for others. I was there as Michelle, not as a therapist. In fact, nobody there asked or wanted me to show up as a therapist. The fact that I was selected to attend the conference is proof in itself that there is something that I could offer within the advocacy space, even if I am a "newbie." There is something that I could offer by simply being myself, and I was allowed to be myself (whoever that is). Listening deeply is part of who I am, but absorbing others' pain does not have to be. Once I gave myself permission to let go of the helper role and the imposter syndrome while understanding that I could be present without absorbing everything, something inside of me shifted: I started to share and listen without performing emotional labor.

As a result, my body felt lighter. My energy felt different. As someone who lives with IBD and chronic fatigue as a constant companion, I hardly ever feel energized. Yet in that space, surrounded by community and safety, I felt more awake and alive than I have in years. I slept through the night without restlessness or insomnia, and I rested without guilt. That establishment of safety ultimately allowed my body to shift out of survival mode, which is the foundation of many evidence-based theories. I felt at home in a way I did not expect. I finally saw that I was allowed to accept help and let people in, even if they were going through their own struggles. I saw how support can be mutual and balanced. I also saw how I could be the "supported" instead of the "supporter," especially by how the HealtheVoices organizers took care of me without requiring anything in return. Letting myself step into that truth felt like exhaling after years of holding my breath. It felt like the relief that comes from finally unclenching my fists and jaw. It reminded me how much chronic illness is affected by environment and emotional safety because healing is not only medical, but it is also emotional and communal.

Overall, this experience made me realize how rare it is to just feel safe in everyday life. At HealtheVoices, everyone had something, whether it was a chronic illness, a disability, or the role of being a caregiver. Illness was not the exception. Rather, illness was the normal. By that, I mean that caregivers and those with health challenges were not the minority, and we did not feel out of place. That shift in perspective changed how I saw myself as it made me feel entirely human. Despite my symptoms persisting due to their chronic nature, I did not necessarily feel "disabled." I did not feel "different" or "abnormal." I did not feel like my everyday reality was "too heavy" or "too personal" to be shared. It was simply life, and almost everyone there understood.

The environment created at HealtheVoices highlighted a crucial truth: the world can accommodate people living with chronic illness, but spaces simply choose not to. The conference gathered people with vastly different conditions and needs, and yet everyone I met felt included and supported. This was not magic. This was intention. This was care. This was a commitment to treating people with chronic illness as fully human. I felt that my needs mattered and that I mattered. The organizers did not treat accommodations as burdens but rather as standard practice. This was eye opening because many institutions act as if inclusion is too much work, but this conference proved that it is entirely possible. In fact, it showed me that inclusion is completely achievable when people genuinely want to create it. To put it simply, inclusion is a choice. Dismissing people is also a choice. Institutions, workplaces, and communities can make room for us, but they simply choose not to invest in the effort.

I left the conference with a heart full of gratitude for the connections I made, the stories I heard, the jokes I shared, the insights I gained, and the revitalized sense of identity that I fostered. I left with a deeper understanding of caregiver burden and the emotional landscapes of people living with all types of conditions. I left with the lived experience of how community is essential for healing. I left with a reminder to show up authentically, even in spaces that do not always understand. I left with a deeper commitment to advocate for people with IBD and for people living with chronic illness(es) more broadly. I laughed more than I expected to, and I actually felt real joy. I left with the realization that I often carry emotional burdens for others and take on roles that are not mine to hold, and that realization is going to guide how I move forward in my personal and professional life.

Most of all, I left with a renewed determination to push for environments that truly include people with IBD and other chronic conditions. We deserve to feel normal, included, and valued. We are not abnormal. We are simply made to feel that way by systems that refuse to accommodate us. Anyone can become disabled at any time through illness, accident, age, etc. Anyone can become sick. Anyone can get hurt. Everyone ages (or at least that is the end goal). It is easy to not be concerned about something that does not affect you, but take it from me, it is 100% possible to wake up sick one morning and never be able-bodied again. That is the story of many people with IBD and many people with chronic illnesses. Inclusion matters because disability affects all of us eventually. Anyone can shift into the world that I navigate every day. In turn, inclusion genuinely benefits everyone.

All in all, HealtheVoices reminded me that despite my IBD, I am not alone—I never was. It reminded me that there are some spaces where people like me can feel completely safe, completely understood, and completely ourselves. There are places in the world where people with IBD can feel completely and beautifully at home. Being in such a space where chronic illness and disability is the norm shifted my understanding of what it means to feel "normal." It showed me what true accommodation, accessibility, community, and compassion look like. It showed me what is possible when people choose care over convenience. It proved to me that inclusion is not only possible, but it is deeply worthwhile. I will carry that truth with me and continue advocating for a world that chooses to see us, support us, and welcome us as we are. And for that, I will be forever grateful.

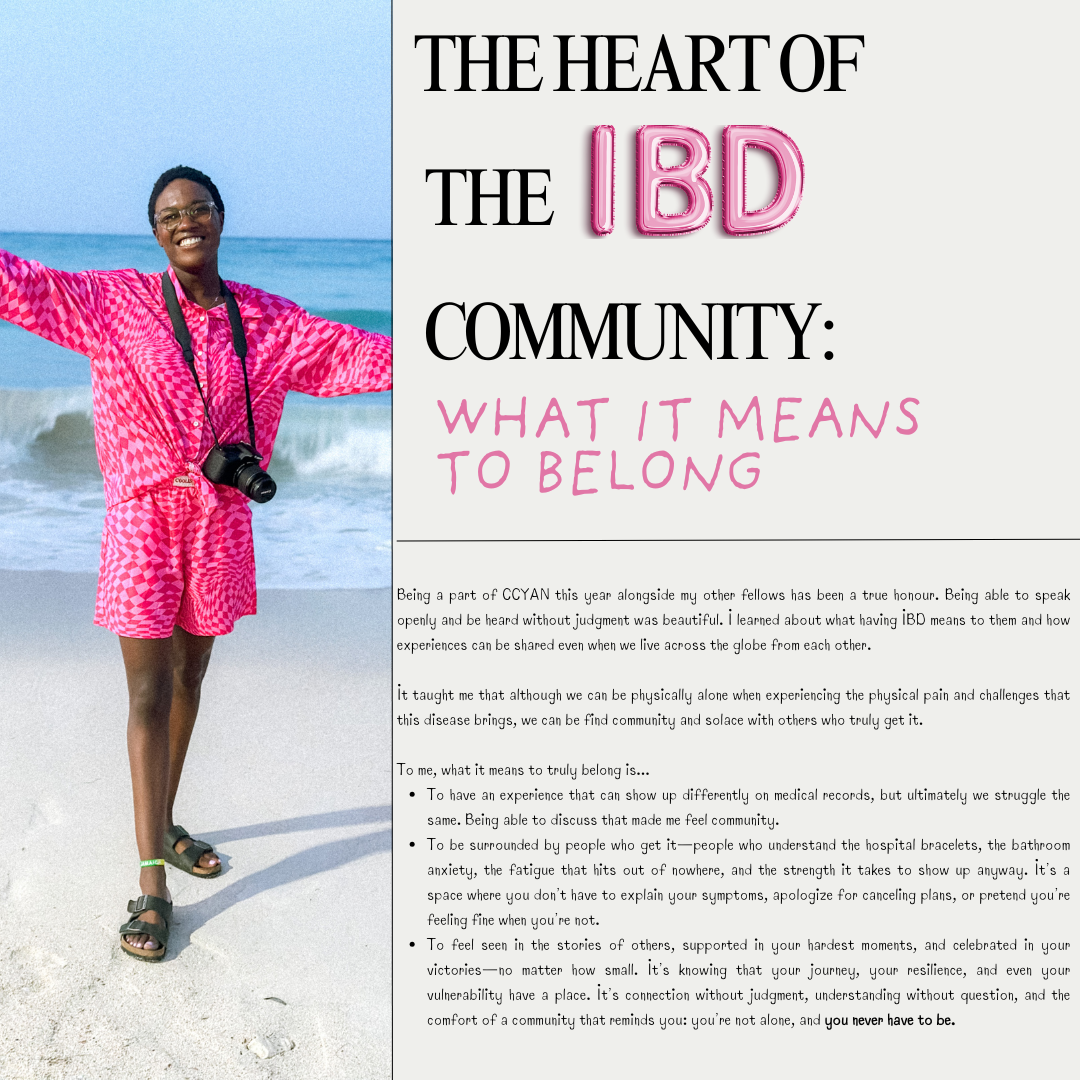

The Heart of the IBD Community: What it Means to Belong

by Lexi Hanson (Missouri, U.S.A.)

Being a part of CCYAN this year alongside my other fellows has been a true honour. Being able to speak openly and be heard without judgment was beautiful. I learned about what having IBD means to them and how experiences can be shared even when we live across the globe from each other.

It taught me that although we can be physically alone when experiencing the physical pain and challenges that this disease brings, we can be find community and solace with others who truly get it.

To me, what it means to truly belong is...

To have an experience that can show up differently on medical records, but ultimately we struggle the same. Being able to discuss that made me feel community.

To be surrounded by people who get it—people who understand the hospital bracelets, the bathroom anxiety, the fatigue that hits out of nowhere, and the strength it takes to show up anyway. It’s a space where you don’t have to explain your symptoms, apologize for canceling plans, or pretend you’re feeling fine when you’re not.

To feel seen in the stories of others, supported in your hardest moments, and celebrated in your victories—no matter how small. It’s knowing that your journey, your resilience, and even your vulnerability have a place. It’s connection without judgment, understanding without question, and the comfort of a community that reminds you: you’re not alone, and you never have to be.

Diagnosis is a Light, not a Lamp Shade (Mental Health & IBD Series)

by Aiswarya Asokan (South India)

It was on May 2nd 2016, a day before my 19th birthday, for the first time in my life, I heard the word Crohn’s, from my doctor back then. It came as a scientifically valid explanation to all the so-called “sick drama” I was exhibiting through the years. But the excitement of this achievement soon faded away when I came to know that there is no cure for this. Then came the joint family decision, we will keep this diagnosis a secret to ourselves. Anyways, who is going to accept me if they know I have got a disease that makes me run to the toilet and that I have to be on regular medication to stop this from happening. For the next 4 years, I lived like a criminal, fearing for every breath this crime will be caught. In between, I was ill informed about the dietary restrictions I was supposed to follow, and kept eating triggers from time to time, meanwhile wondering why this is happening – but was still focused on keeping the secret safe.

Still, life was a smooth sail with a few days of bad weather here and there, till 2020, when I had my worst nightmare: a serious flare that left me hospitalized for more than 2 months and unable to take my final year university exams. And my secret was out. Not being able to appear for exams was too much for an academically excellent student like me. I was experiencing such intense pain that I couldn’t even turn sides in bed. All this made me question my identity and shattered my fundamental belief system. None of the medicines were working on me. A group of surgeons visited me, and told me that if surgery was attempted, my life might be over on the table. When I realized I might die soon, I decided to live a little. Even though I was not able to eat anything, I ordered a red velvet cake and ate it. The 2020 Tokyo Olympics were going on – it was my all-time wish to watch the Olympics live, but my academic schedule did not allow me to do so. So from the hospital bed, I watched Neeraj Chopra win a gold medal for India, while all my classmates were taking final year exams.

After a while, steroids started working and I started getting better. At the age of 23, I was 33 kilograms, severely malnourished and on a high dose of medication. I was not afraid to die but coming back to normal life was a challenge. I couldn’t face people nor attend phone calls. Even notifications from messages were alarming for me. I zoned out from everyone around me. I felt myself as a complete failure.

One person kept on calling me, despite me ignoring all their calls, until one day I finally picked up. He was my childhood bestie, who stood with me till I was able to manage things on my own. He made a timetable for me, which included slots for physical activity, exam preparations, and fun activities, and made sure I followed them on a daily basis. Then the exam date came up. There were times when I took supplementary exams alone, in a hall that usually accommodates 60 students. Everyday after the exam, he would ask me how it went, and suggest a movie to watch as a reward for the hard work. After a while, exam results came, and I had the highest score than previous years. Life was again on.

Whenever a flare up hits me, the first thing I notice is a keen desire for physical touch, especially a warm hug, though it sounds strange. I also clench my jaw while asleep, to an extent that my whole face and ears start to hurt the next morning, which further makes it hard to have food. Within the next 3 years, time was up again for a rollercoaster. I had a stricture, unbearable pain, my oral intake was nil, and I had to go for a hemicolectomy. The anticipated complications for the surgery were extremely frightening. This time my boyfriend came up and assured me that “no matter what, I will be there for you.” The surgery went smoothly and I was discharged. I was physically fit but started experiencing PTSD-like symptoms. I started feeling I was just a financial burden to my family.

I slept all day and night as I was not ready to face the thoughts in my head. My boyfriend used to call me every day – just for those few moments I was living, but the rest of the time I used to sleep. This time no friends nor family could help me. Then I started searching for IBD support groups, came to know about IBD India, took the free mental health counselling, and joined the peer group. For the first time, I felt less isolated and felt a sense of belonging. And slowly I replaced my coping mechanism of sleeping with painting. Gradually I was healing, and started feeling more freedom like never before.

Life goes on. Ups and downs are part of it. But when one door closes the other opens. When you feel stuck, ask for help and keep asking until you get one strong enough to pull you out — that is the bravest thing you can do for yourself.

Image from Unsplash.

Listening to Your Body with IBD: The Stoplight System

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

When you're living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), your body becomes its own navigation system. Your body is constantly sending you signals, just like traffic lights do. But unlike the red, yellow, and green lights on the road that we instantly respond to, many of us with IBD have learned to ignore or minimize the "rules" or "drills" that we should follow when our body sends us our own, personal warning signs.

So why is it that we respect a blinking car dashboard, a low battery warning on our electronic devices, and traffic signals/signs more than the signals coming from our own bodies? We wouldn’t ignore our car’s check engine light for weeks (and if we did, we’d expect it to eventually break down). So why do we ignore our body’s warnings? Why don't we listen? As with most things, the answer is complicated.

Here are a few reasons why as people living with IBD, we might forget to listen to these warnings, or try to “push past” them:

Living with IBD means that a few warning lights are always on. That is, we might always have some level of fatigue, bloating, or discomfort. This "always-on" background noise becomes our new normal, and we stop noticing when new signals show up. This is risky because it can lead to ignoring major warning signs or missing slow-building flare-ups.

Our symptoms can become our new normal or "background noise," so we're used to pushing through pain. This means that even when our bodies give us that "red" or "yellow" light signal to slow down or stop due to a symptom/pain that is out of the ordinary, we are still conditioned to push through it. For a lot of us, that is a survival mechanism of having chronic pain (pain that never fully becomes "background noise") in a medical system and society that often tells us to "push through." The world is constructed for those who are able-bodied, and having chronic pain/IBD can force us to sink or swim.

We are often taught to minimize our symptoms, for ourselves and others. Sometimes, doctors dismiss our warning signs, maybe because medical literature doesn't acknowledge all the intricate traffic signals for IBD. Maybe, they're just burned out. Or, maybe doctors—and people in general—can't fully understand the severity of IBD symptoms if they haven't gone through it themselves. Whatever the reason, though, we are conditioned to minimize our symptoms. We are taught that our illness "could be worse." In fact, when explaining IBD to others who don't quite listen closely enough, the false notion that IBD is simply "stomach problems" circulates. So much so that we, ourselves, sometimes say this to others or even believe it ourselves. We don't want to be sick. We wish it was just stomach problems. Being told that our personal traffic lights/signals are simply a result of "anxiety" or "are in our heads" make it easy to eventually believe it ourselves because, why would we want to be sick?

We don’t want to "miss out." Sometimes, we’d rather have a moment of fun—followed by a flare/low-spoons day—than not experience the fun at all. Ignoring the signals can sometimes feel "worth it" since it can give us a small glimpse of what "normal" might be like. We are forever torn between the notions of "respect your body's limits" and "you only live once."

Finding a way to make a choice, despite the consequences, can feel liberating in the short-term. This can look like eating a food that you know isn't "safe" just because you want to make a CHOICE and have autonomy over your own body. As IBD patients, choice is often not in our vocabulary – so pushing through the pain of IBD is often the only way we can feel slightly in control of our own bodies. This is a sense of freedom that we greatly lack as IBD patients.

We don't want to be a “burden.” IBD, in itself, is a burden that we already have to carry. Living with it every day is extremely difficult, and that is an understatement. Even so, we still notice how it affects those around us— our caregivers, partners, family members, friends, co-workers, employers, and even doctors. Carrying the burden alone is never the solution, but it sometimes seems like the right one since it feels wrong to allow someone else to feel even remotely similar to us. It doesn't feel right to allow anyone to be down in the trenches with us—at infusion appointments, at ER visits, at ICU admissions, or at "bathroom sleepovers." It doesn't feel right to allow anyone to feel so wrong, even if they want to. Therefore, we ignore the signs, because if we took action that would mean that we'd need help, whether we like it or not. We'd have to reach out to someone, even if that's just a doctor. Simply alerting your doctor that you've failed another biologic can make you feel like a burden since you might feel as though you're giving them more work. Reaching out to loved ones can be even harder as they will often want to be there for you, and you simply don't want to burden anyone anymore.

We’re afraid of what we’ll find if we stop and really listen. As previously mentioned, we don't want to be sick again. We don't want to discover a new co-morbidity again. We don't want to switch medications again. We don't want to be flaring again. We don't want to go to the hospital again. We don't want to experience medical trauma again. We don't want to put life on pause again. We don't want to miss out again. We don't want to be a burden again. We don't want to lose control again. Listening to your body, and truly paying attention to what it's telling you poses the risk of you having to accept the fact that you might have to go through all of these things again. And at the end of the day, we just want to live—freely. It feels like a constant tug-of-war between surviving and actually living.

The truth is: Your body will always tell you what it needs. It’s just your job to check in—gently and consistently.

Since there is no cure for IBD yet, much of this disease has to do with symptom monitoring and, thus, taking as many preventative measures as possible. I, for one, know that I would like to stay in remission and avoid a flare-up for as long as possible. Even so, I know that's only possible if I listen to my body—genuinely listen. Whether that's taking note of unusual fatigue or nausea, a new sensitivity to food, etc., these are acts of listening to your body and its signals. While we are taught from a young age what traffic lights mean and why it's important to follow them, we aren't taught how to notice and follow the signals that our bodies give us.

A few simple things that you can do to start the practice of ‘checking in’ with yourself and your body:

Create your own ‘traffic light:’ write down some of the signs you notice, when you’re feeling ‘green, yellow, or red!’

Set aside a few minutes each day to ask yourself: What "color" am I today? What makes me that color? What am I feeling, and where am I feeling it? If I’m yellow or red, what needs to change? If I’m green, what can I do to stay there?

Not sure where to start? Here’s an example of my “traffic lights,” and some of the signals I use to check in with myself and my body!

A few things to remember/keep in mind:

Checking in doesn’t mean obsessing. It simply means being mindful enough to care. Just like we do for our phones, our cars, and our jobs—we deserve to offer ourselves the same level of awareness, support, and maintenance.

Living with IBD doesn’t mean you’ll always be stuck in red or yellow. Some days are green—some weeks or months, even. You deserve to honor those days as much as you manage the hard ones.

This stoplight system isn’t about fear. It’s about empowerment. You are not weak for needing rest, medical support, caregiving, or time. You are wise for knowing when to go, when to slow down, and when to stop.

Your body isn’t the enemy—it’s the messenger. Listen to it. Trust it. Respond with love. Your body is doing the best it can to keep you alive. Let’s return the favor.

Image from @tsvetoslav on Unsplash.

IBD: I Battle Daily

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has taught me an unforgettable truth, that is the battle I face every single day. It is not a one time event or temporary struggle, it is an ongoing challenge that affects every part of who I am. It is not just physical, it is emotional, mental and spiritual. Every decision I make has the power either to support my healing or challenge it.

From my personal journey, I have learned something I believe is absolutely essential for a person living with IBD: understanding our condition is crucial. The more we know about IBD – the symptoms, the triggers, the treatment options – the better prepared we are to manage it with strength and confidence.

But I have also come to realize another powerful truth: what works for me might not work for someone else. Each of our bodies is beautifully unique, and that is why it is so important to slow down, reflect, and truly listen to your body.

IBD is not just about following a set of rules someone else wrote, it is about discovering and honoring your own rhythm.

I once heard my lecturer say, “I ALWAYS STAY ON MY SAFE SIDE.” That one sentence echoes in my mind on tough days. For those of us with IBD, our safe side is not just a place, it is a mindset. It is the knowledge we have gathered, the awareness we have cultivated and developed about our own bodies. Staying on our safe side means respecting our limits and standing strong in what we know helps us.

Let this journey inspire others to do the same. Let it be a reminder that even in the face of invisible battles, we have the strength to rise. Let it encourage every IBD warrior out there to listen closely to their bodies and to honor their unique paths with pride and resilience.

We fight daily not just with medication, but with courage, care, and community.

Image from Unsplash.

Through

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

World IBD Day is May 19th, and this year’s theme is “Breaking Taboos, Talking About It.” Here are 2025 CCYAN Fellow Michelle’s thoughts on stigma, shame, and talking about IBD!

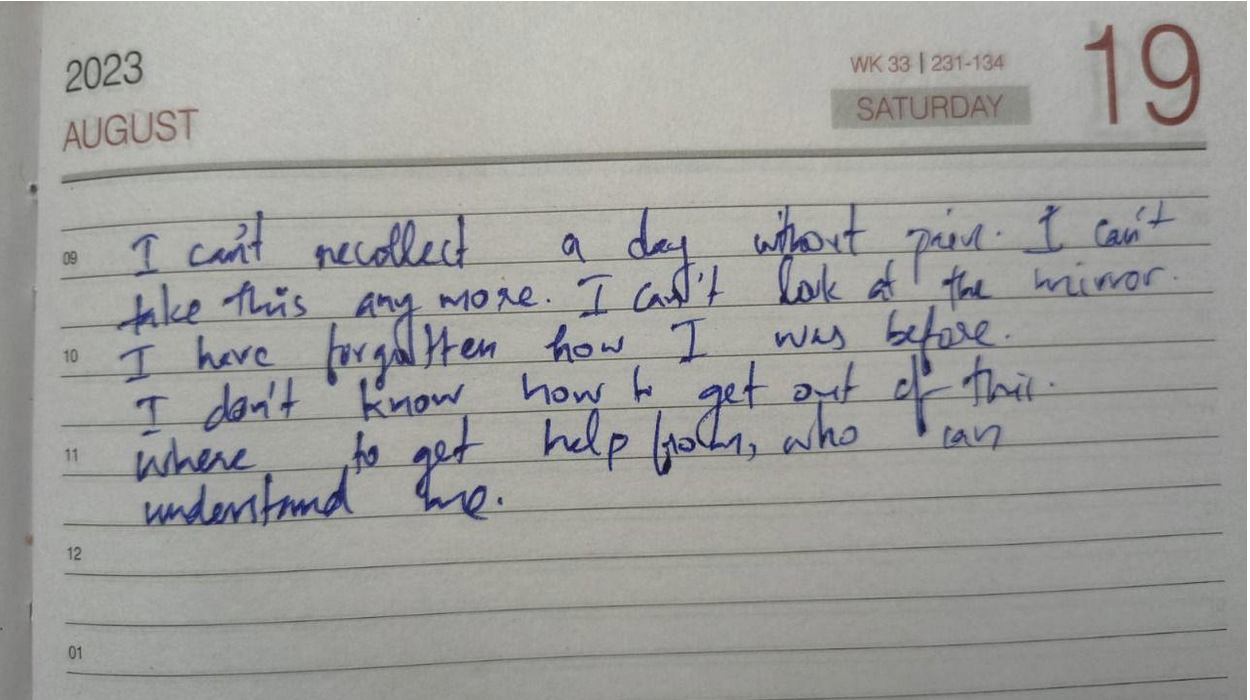

Since being diagnosed with Ulcerative Pancolitis almost four years ago, I have been battling the shame that surrounds my symptoms. I often look back at who I was before my diagnosis—not only grieving that version of myself but also feeling ashamed that I can never fully be her again. Before IBD, I was fiercely independent, reliable, spontaneous, perfectionistic, energetic, athletic, social, focused, happy—and, most importantly, healthy. To put it into perspective: I was a straight-A student at a top magnet school in my district with a 4.44 GPA. I was simultaneously taking college classes, volunteering, traveling, going out with friends, exercising, and serving as the Secretary of my high school’s dance production team. Even during my first year of university—despite COVID-19 restrictions—I took 33 credits, earned leadership positions, made the Dean’s List, got straight A’s, moved into my own apartment, worked out consistently, and started two social work internships.

Then, everything changed. After my diagnosis, my life felt like it had been turned upside down—and in many ways, it had. For a couple of years, I had to move back in with my parents because I could no longer care for myself. There were days that I couldn’t brush my own hair or stand long enough to cook a meal or wash my face. If I needed to go to the hospital, I couldn’t even get myself there. I was fully dependent on my family when my IBD was active. That dependency alone filled me with shame. How could a nineteen-year-old not brush her own hair? How could I be so weak? While I managed to continue online school, I had to request disability accommodations from my university. I went from being someone who never asked for help to someone who needed it in nearly every part of her life. I no longer felt like myself. The woman I once was had seemingly vanished, and in her place was someone I didn’t recognize—someone who carried a constant, heavy shame.

Even now, despite being in remission for about two years, that shame hasn’t disappeared. It creeps in every time I’m too fatigued to answer a text or take a phone call—or worse, when I have to cancel plans. In those moments, I don’t just feel like a bad friend, I feel weak. I feel mentally, physically, and emotionally defeated. I question how someone like me, who seemed to once "do it all," can’t even hold a simple conversation anymore. That shame resurfaces every time I walk into my gastroenterologist’s office or sit in the infusion center waiting room. I think to myself, "Why am I here? I am so young, and yet I am sick. I must just be weak." Even when I pick up a stool collection kit at the lab, I look around, paranoid and embarrassed that someone might know what’s in that big, brown paper bag. I also feel ashamed of what I have to do with that kit once I get home. Especially on the days that I sleep late into the afternoon or feel too exhausted to shower, that shame becomes deafening. I can’t even manage basic self-care, and that makes me feel pathetic and exposed.

Unfortunately, I used to feel as though this shame only deepened when I tried to speak up about what I was going through. On a romantic level, I used to be extremely cautious about sharing my IBD with potential partners. This is because I didn’t want to feel embarrassed, and I certainly didn’t want to be rejected because of it. My first partner after my diagnosis knew all about my IBD. We joked about bathroom "duties" constantly—it was part of our daily rhythm. Beneath the humor, though, I knew that he wanted someone different: someone who could be spontaneous, who could have endless energy, who could cook large meals, who could host frequent gatherings, who could clean, who could work out with him, etc. That just wasn’t me anymore. I also knew that he didn’t want to be around if I ever needed to take Prednisone again since I had explained its emotional toll and side effects. Moreover, I knew that he would "never touch" me if I ever had to get an ostomy. So, I tried to be who he wanted—to become the woman I was before IBD—and for a while, I pulled it off. Over time, though, that relationship made me feel unaccepted—for who I was in that moment and for who I might become. It made me feel ashamed to be me—the real me. It intensified the shame I already carried about my illness.

Since then, dating has been rocky. I’ve met a few people who've responded with deep empathy and genuine interest, and for that, I am grateful. I’ve also encountered individuals who shut down any conversation about IBD out of their own discomfort, who incessantly question my fertility or the "quality" of my genes, or who firmly believe that "tooting" in private or using the word "poo" in a sentence would be impolite and inappropriate. For someone who loves deeply and craves a meaningful romantic connection, those reactions cut deep. They make me question and feel ashamed of the kind of partner I am—or could ever be. On a platonic level, things haven’t been easier. When friends or family joke about me "sleeping all day," "always being at home," "always needing the bathroom," "being forgetful," "not being fun," "eating boring foods," or about how my brother "takes better care" of my dog, shame crashes over me like a wave. I genuinely begin to drown in it. It’s one thing to feel shame for not meeting your own expectations—the ones you set when you were healthy. It’s another to feel shame when romantic partners judge you for something you didn’t even choose and cannot control. However, it’s something entirely different, and perhaps even more painful, to feel that shame reinforced by the people you love and value the most. When they unknowingly echo the same critical thoughts that I already battle every day, it doesn’t just hurt—it reinforces my shame and makes me feel weak and unworthy.

This compoundedness and deeply personal nature of this criticism take my shame and embarrassment to an entirely different level. The intensity of shame I’ve felt in these moments mirrors the shame I’ve carried throughout my journey with active IBD symptoms. It mirrors:

The shame I felt needing my loved ones to brush my hair;

The shame I felt crying, begging, and pleading with doctors for answers and relief;

The shame I felt discussing my symptoms with countless medical professionals;

The shame I felt from the burn marks and scars left behind by overusing a heating pad;

The shame I felt experiencing fecal incontinence;

The shame I felt wearing diapers for months;

The shame I felt needing to carry baby wipes, toilet paper, and a change of clothes;

The shame I felt when I could no longer clean myself without help;

The shame I felt asking my gastroenterologist to remove my colon;

The shame I felt when I began to question if life was even worth living;

The shame I felt being bedridden, needing a wheelchair just to get fresh air;

The shame I felt requesting accommodations from my university;

The shame I felt when a doctor asked me why I waited so long to seek help.

Still, I continue to grieve the version of myself I once was, and I wrestle with the shame of not being able to live up to that image again. Feeling stuck in your own body when your mind wants to do so much more is an agonizing experience. I acknowledge that fully. Yet—despite my doubts—those feelings of shame began to fade away as my symptoms have lessened and as I’ve found my voice within the IBD community. I've recently been able to feel pride when comparing the person I once was to the person I am today. No, I may never again be the energetic, healthy "yes woman" I once was. Nevertheless, I wouldn’t have the resilience, empathy, and sense of purpose I now carry if not for IBD. Fighting for your life, navigating a new reality, and battling stigma while the world moves on without you teaches you something profound: you are capable of surviving the unimaginable.

With this new revelation and mindset, I've come to see how my feelings of shame and beliefs of being weak/perceived as weak are rooted in fallacy because:

To cry in front of doctors and explain your symptoms is not shameful—that's strength.

To be vulnerable and advocate for yourself is not shameful—that's courage.

To decline a call, cancel plans, say "no," and set boundaries is not shameful—that's self-respect.

To rest rather than push through the pain is not shameful—that's self-love.

To wear diapers and pack supplies to manage your day is not shameful—that's determination.

To request or actually go through a life-altering surgery is not shameful—that's bravery.

To need and/or ask for help is not shameful—that's survival.

To live in a body that is constantly fighting against you is not shameful—that's perseverance.

To choose life every day, despite IBD's messiness and pain, is not shameful—that's resilience.

Furthermore, I believe with all my heart that talking openly about IBD—the good, the bad, and the ugly—is one of the greatest testaments of one's strength. Whether it's with friends, partners, family, co-workers, medical providers, or strangers, it takes immense courage to be that vulnerable. This is because, in all honesty, there is risk involved. As human beings, our minds can sometimes jump to the worst possible outcomes. When it comes to talking about IBD, there's the risk of being judged, pitied, and misunderstood. There's the risk of "becoming" your diagnosis and of losing relationships or job opportunities due to stigma. These fears are real and valid, and they’re exactly why many IBD patients tread lightly when sharing their stories. As a result, though, we often overlook the best possible outcomes. From experience, I know that talking about your IBD can: help you feel more at home in your own body; help you feel accepted for who you truly are rather than who people want you to be; help you find community; help shine a light on the genuine/empathetic people in your life; help create space in your mind for something more than just survival; help break the stigma; and help pave the way for earlier diagnoses, better treatments, and stronger support systems. Sharing your story doesn’t make you less—it makes you more. Sharing your story makes you more human, more whole, and more you than you had ever thought possible.

Taking all of this into account, I’ve come to recognize how powerful it can be to talk about IBD and share your story. If the worst that can happen is being judged, excluded, misunderstood, or left, then maybe talking about your IBD is a blessing in disguise. I know that speaking openly about my IBD has saved me from dedicating my energy and love to people who didn’t deserve it. If the best that can happen is finding your people, becoming more comfortable with your diagnosis and yourself, getting care faster, and helping to break the stigma, then sharing your story might actually be a superpower. We, as IBD patients, are in a unique position to educate and advocate—not because it’s our responsibility, but because our lived experiences often speak louder than medical textbooks ever could. I wish we lived in a world where everyone understood IBD, where institutions offered protection, and where systems were built to accommodate us. The truth is, though, most people just don’t know where to start. They rely on what they read online or hear in passing. It’s easy to see how misconceptions and stigma grow. If I read online that remission meant "no symptoms and a healthy colon," I probably also wouldn’t have much empathy for someone in remission who still canceled plans or needed extra rest. As someone in remission who is sharing her story, though, I can tell you one thing: that version of the story isn’t quite right. Nothing about IBD is so black-and-white. Everyone’s experience is different, which is why personal storytelling matters so much. Doctors, loved ones, and even other patients learn from us as IBD patients. So many vital conversations—about non-textbook flare symptoms, about “safe foods,” about unspoken medication side effects, and about what remission really looks like—don’t come from medical journals; they come from people with IBD who tell the truth about what it’s actually like. Without these stories, diagnosis and treatment can be delayed, and support systems stay broken. It’s not our job to fix the system, but by speaking up, we might just make it easier for those who come after us. We might even make it easier for ourselves in the future.

For a disease that has made me feel powerless more times than I can count, finding power with or over my diagnosis has been invaluable. Talking about IBD has helped me reclaim my own narrative. People can still judge me, but at least they’re judging something real. If someone can’t handle a story of resilience, that’s on them. No journey of survival is without its dark moments. Most movements worth remembering were forged in hardship.

That said, I don’t want to pretend it’s easy. Even now, I still struggle to talk about my IBD. I just recently began experiencing symptoms of a flare, but I only told my doctor and loved ones after a delay. This was not out of embarrassment, but out of fear—the fear of returning to that time when I felt that I had lost all independence, the fear of being blamed, and the fear of blaming myself. There’s a voice in the back of my mind that whispers, "You should’ve taken better care of yourself. You should've been stronger." And although I know that’s not true, it still stings.

Even with that fear, though, I eventually reached out because I’ve learned what happens when I don’t. I know now that silence doesn’t save me. Hiding doesn’t protect me. Every time I have tried to ignore a symptom or push through for someone else’s comfort, I’ve paid for it tenfold. I've realized that delaying diagnosis and treatment is, quite frankly, not worth anything. So, I’ve started doing the hard thing: I've started telling the truth. I’d rather speak up than wait until things become unmanageable because the truth is, IBD is messy. It’s not just a bathroom disease. It’s not just about inflammation or test results. It’s about what it does to your relationships, your identity, and your sense of safety in your own skin. It’s about mourning the life you thought you would have, and then figuring out how to build a new one—without pretending that the old one didn’t matter. It’s also about power—quiet power. This is the kind of power you reclaim when you speak up, when you stop hiding, and when you say, "Here’s what I’m going through," even if your voice shakes.

I know what it’s like to walk into a doctor’s office, share your story, and be dismissed. I know what it’s like to be lonely in a room full of people who love you. I know how scary it can be to share what you're going through. At the same time, I also know how healing it can be. Talking about your IBD—when you’re ready—can give you strength with the diagnosis and over the stigma. That kind of power is slow and sacred. It doesn’t always feel good, but it builds something stronger than "perfection" and "control." It builds truth. When I tell my story, I don’t just feel more seen. I also make space for other people to show up with their stories. Sometimes, your courage can be the reason someone else finds theirs and feels less ashamed. The more we speak, the less shame survives. The more we share the parts of IBD that don’t have tidy endings, the more human this disease becomes rather than being a punchline of a joke or a pity project. There are days that I still feel afraid—afraid of being judged, misunderstood, and left behind. Even so, I’m more afraid of going through this alone. If my story can be a hand reaching out to someone else in the dark, then I’ll keep telling it—again and again. At the end of the day, I truly believe that the only way out is through, and for me, the "through" begins with sharing my story.

God of Small Things, Arundhati & THE LOVE EQUATION - A Crohn’s View

by Rifa Tusnia Mona (Dhaka, Bangladesh)

Stigmas Have Power! You might wonder why I say this as an IBD advocate. After all, stigmas are often baseless and untrue. But when they come at you from all directions—constantly, persistently—they start to wear you down. That’s when the real distraction, aka destruction, begins.

Imagine this:

One morning, you wake up feeling like something is coiling and twisting inside your stomach. You can’t eat. Or if you do, your body refuses to digest. Nausea takes over. You vomit again and again. The cramps hit without warning, stabbing, vanishing, then returning like waves from a storm. You feel trapped in a body that’s turning against you.

At first, people think it’s temporary—just a bug, maybe food poisoning. But then, something changes. The concern fades, and in its place, they start labeling you.

One morning, your mother decides to take you to church. If you’re Muslim, maybe it’s a hujur or a Sufi healer. Neighbors drop by. They don’t bring comfort; they bring unsolicited advice. "Have you tried this doctor?" "You should pray more."

Later, one morning, you find yourself lying in a hospital bed. A nurse enters and says, “Ask God for forgiveness.”

It hits differently. You’re not just battling a disease anymore—you’re battling judgment.

That’s the thing about stigmas: they’re powerful because they echo from everywhere. Different mouths, same message. And it always seems to come when you’re at your weakest.

But the hardest part?

When it comes from the people you love—your friends, your family—the ones who’ve always stood by you. That’s when the real confusion begins. You think, They care about me. They’ve never meant me harm. So maybe… maybe they’re right?

And just like that, you start to question yourself—not your illness, but your worth.

It took me a long time to realize that human minds are incredibly complex. I used to carry the weight of every cruel word, every dismissive act, thinking I must’ve done something to deserve it. But over time, I began to understand: most of the time, it’s not about me.

People don’t always act from a place of clarity or kindness. Sometimes, they hurt others to soothe an old scar within themselves. Sometimes, they mirror the pain they once suffered. And sometimes, they hurt simply because they don’t know how not to.

That’s when it hit me—pain is transferable.

It doesn’t just live in one person; it moves, it multiplies, it morphs into behaviors, into beliefs, into judgment. And many of those who hurt us are, in fact, carrying unresolved pain of their own.

“The God of Small Things” by Arundhati Roy feels like a masterpiece to me—layered, lyrical, and hauntingly beautiful. But if I had to pick one part that truly stayed with me, it would be the part about what Roy calls ‘The Love Laws’—or, as I like to think of it, the unspoken equation of love.

“That it really began in the days when the Love Laws were made. The Laws that lay down who should be loved, and how, And how much.”

-Page 33, Chapter 1, Paradise Pickles and Preserves, The God of Small Things

According to this idea, the amount of love we receive can sometimes feel predetermined—set by invisible rules we never agreed to. From Arundhati Roy’s words, I understood that love is often measured through two things: care and concern. These are the true units that define the depth of a relationship.

For love to feel genuine and meaningful, both must be present—together. When only one shows up, or when they're offered inconsistently, the relationship starts to feel imbalanced. It turns into something less whole, something we try to justify as "complicated" or label as, “Please, try to understand.” But deep down, we know—it’s a compromised connection.

“After Ammu died (after the last time she came back to Ayemenem, swollen with cortisone and a rattle in her chest that sounded like a faraway man shouting), Rahel drifted. From school to school. She spent her holidays in Ayemenem, largely ignored by Chacko and Mammachi (grown soft with sorrow, slumped in their bereavement like a pair of drunks in a toddy bar) and largely ignoring Baby Kochamma. In matters related to the raising of Rahel, Chacko and Mammachi tried, but couldn’t. They provided the care (food, clothes, fees), but withdrew the concern.”

-Page 15, Chapter 1, Paradise Pickles and Preserves, The God of Small Things.

There was a time when I was hospitalized for over a month. My father had a full-time job, and my mother had to juggle between caring for me and my younger sister. With both of them stretched thin, I reached out to every friend and relative I knew, hoping someone could step in as a caregiver. But no one came forward.

I was already battling an undiagnosed illness, and on top of that, navigating hospital departments alone, collecting test results while being so physically unwell—it felt like walking through fire. In that moment, a thought struck me hard: “After living over two decades, have I still not understood the love equation?”

Living with a chronic condition like Crohn’s has, in a strange way, been like being handed a special lens. I began to see certain relationships for what they truly were—fragile, one-sided, and built on illusions. That clarity gave me the strength to say “No” and walk away from connections that no longer served me.

It might sound harsh, but when your body is already carrying so much pain, the weight of empty relationships and unmet expectations becomes unbearable. Letting go became a form of relief, a way to breathe again. I’ve come to believe that sometimes, releasing old bonds opens up space for new, more meaningful ones. And life, quietly but surely, moves forward.

In a world where being "different" is often taboo, genuine relationships—the ones rooted in care and understanding—can feel like a warm shield. They make all the difference.

These are just my reflections, and as a reader, you’re welcome to hold your own. But thank you for making it this far—I appreciate your presence here, and I hope to meet you again in my next write-up.

Featured photo by Kaboompics.com from Pexels.

I am more than what you see: Living with IBD body changes

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Living with inflammatory bowel disease, my body has changed in ways I didn't choose. People see my outward appearance and make assumptions. Often, they don't wait to hear your story, and they judge you based on your size or looks: no words, no chance. It hurts because words can't always express what we feel inside.

They don't see the battles I fight every single day. I’ve heard it all:

"You are too skinny."

"You don't look strong."

"You must not eat enough."

But I know myself - I am strong. My journey is filled with courage, healing and hope. I don't have to be judged by my size, I am more than that. My size doesn't define my strength, my resilience does.

I have faced many tough times, but people don't see me as a serious person because of my appearance. I have survived painful flare ups, countless hospital visits, difficult medication side effects, surgery, and emotional lows and that could have broken me.

And yet, I am still here: still standing, still fighting.

I may not have a body society views as "tough," but I carry strength in my spirit.

I carry it in my story.

Being judged by my body and appearance has been painful, but it has also taught me what really matters: my ability to rise again and again.

I am not a slab of meat to be consumed or judged. Your power lies in what you overcome, not in the size of your frame or your appearance. We are more than our bodies, we are warriors.

No one knows what tomorrow holds, and what we have today is not guaranteed. Life changes, and bodies change, but our worth remains. Let’s learn to see beyond appearance, and appreciate our strength. We never know the silent battles someone is fighting – behind every look, there is an untold story.

Photo by Unsplash.

Navigating the "Why Me?" Season of Chronic illness

Yeabsira Taye Gurmu: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

The "Why Me?" season of my journey with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) was one of the most challenging times in my life. The onset of symptoms—unrelenting abdominal pain, fatigue, and unpredictable bowel movements—left me feeling lost and overwhelmed. Each doctor's appointment felt like a new hurdle, as I faced uncertainty and often dismissed concerns. The emotional weight of confusion, fear, and frustration was heavy, making it difficult to envision a future where I could manage this condition. It was a time filled with questions but few answers, leaving me grappling with the reality of my health.

For new patients experiencing a similar phase, it’s essential to understand that these feelings are normal and part of the diagnostic journey. Expect to encounter a mix of emotions, from denial to anger, as you seek answers. It’s crucial to advocate for yourself and seek support, whether through online communities or professional help. Keeping track of symptoms and preparing questions for your healthcare provider can empower you during appointments, helping to clarify your condition. Remember, this stage is often a tumultuous path toward understanding, and it’s okay to feel vulnerable as you navigate it.

Transforming the "Why Me?" phase into a positive, lifelong attitude is possible. Embrace the challenges as opportunities for growth and self-discovery. Focus on education about your condition, which can demystify the condition and foster a sense of control. Surround yourself with supportive people who uplift you and understand your journey. By practicing self-care and maintaining a proactive mindset, you can turn this difficult chapter into a foundation for resilience and empowerment. Ultimately, this experience can lead to a fulfilling life with your chronic condition, marked by hope and a renewed sense of purpose.

Featured photo by Disha Sheta from Pexels.

Saying No is Ok!

By Isabela Hernandez (Florida, USA)

There are going to be days when your IBD is acting up, and you do not feel up to going to events or seeing friends you’ve committed to seeing. Yet, you feel guilty for saying you don’t feel well. I used to struggle with this heavily. I would have a plan with friends that was made in advance, but the morning of, I’d wake up feeling extremely sick. Many thoughts would be going through my head. Do I go and stay in pain? Do I say I’m sick; would they believe me if I say I’m sick? Why do I feel guilty for changing my mind? I would try to explain to the people around me how I was feeling, but I could see in their faces they didn’t really understand how intensely my IBD affects me, especially socially. To them, me saying no was me bailing on spending quality time with friends for selfish reasons. For me, saying no was the only way I could preserve the sanctity of my physical and mental health. These experiences with friends have taught me many things.

There is NO reason we need to feel guilty for prioritizing our health, whether that be saying no to a friend or backing out of a plan last minute due to symptoms.

If your friends don’t try to understand how your IBD affects your life socially, then it may be time to reevaluate what these friendships mean to you.

Find healthy ways to communicate with the people you are close with to let them better understand your IBD - if you don’t let them in, they’ll never truly get to know you and your disease.

Be open with YOURSELF about what you feel and adjust your day based on that. Everyday is different and that’s ok.

Do what’s best for you!

Now, those around me know when I say, “I’m having some symptoms today, I don’t think I can go,” that it is not personal, but I need to focus on myself that day. I’ve found people who have learned to respect that and really understand what I feel. I challenge you to put yourself first and learn to prioritize your health, even when it’s hard.

This article is sponsored by Trellus

Trellus envisions a world where every person with a chronic condition has hope and thrives. Their mission is to elevate the quality and delivery of expert-driven personalized care for people with chronic conditions by fostering resilience, cultivating learning, and connecting all partners in care.