by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

Disclaimer from Michelle: Johnson & Johnson paid for my travel expenses to attend HealtheVoices, but all thoughts and opinions expressed here are my own. This conference was not attended as a part of the CCYAN fellowship.

From November 6th through November 9th, 2025, I stepped into a space that I had never experienced before. HealtheVoices 2025 was more than a conference for advocates like me. HealtheVoices became a place where my body, story, and heart finally felt understood. I walked in as an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and mental health advocate, but I walked out feeling like I had reclaimed parts of myself that IBD had slowly worn down.

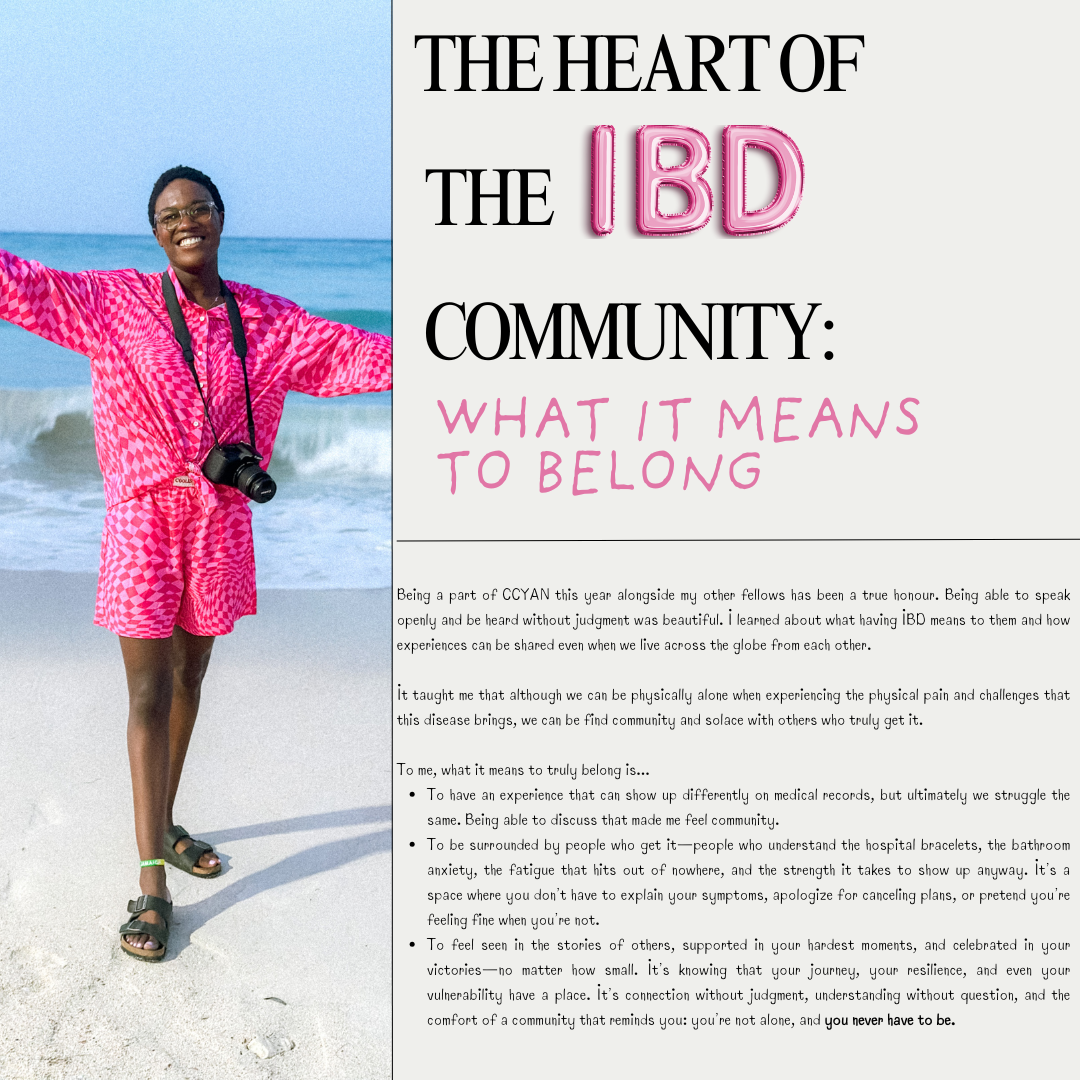

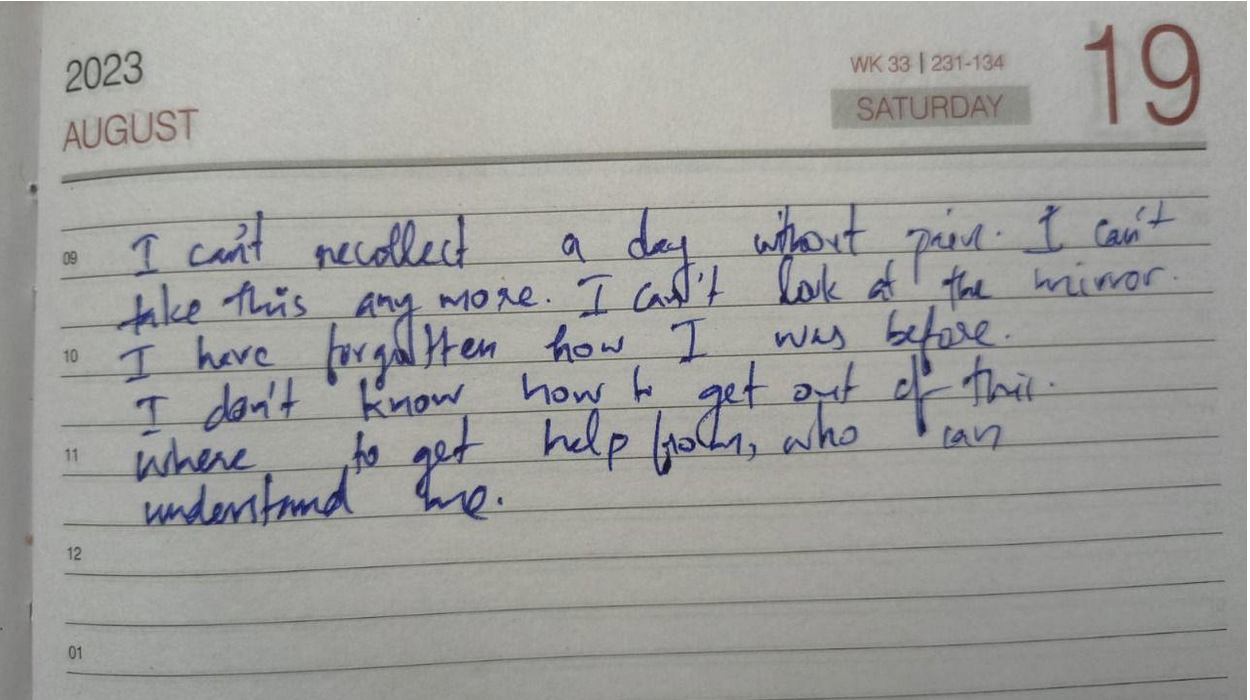

IBD affects so much more than the digestive system. My life is shaped by symptoms that are unpredictable and exhausting, with my mental health experiences running parallel to this journey and adding additional weight. IBD ultimately shapes the way that I move through the world, my energy, my confidence, and even the level of honesty that I bring to conversations. Daily life can feel even more heavy and lonely because it is rare for me to be in a room filled with people who truly understand what chronic illness feels like, and vulnerability about illness does not always land well with people who cannot relate. At HealtheVoices, that weight softened the very moment that I arrived. The environment made me feel safe before I even realized that I had been holding my breath for so long.

I met people living with many types of chronic conditions, from visible disabilities to more silent illnesses like mine. I met caregivers who understood illness from the position of love and exhaustion. I met people who shared my diagnosis of IBD and people who shared my mental health struggles as well. In turn, I finally did not feel like the odd one out or like the only person in the room fighting a battle that no one else could see. For one weekend, I felt truly seen, understood, and supported. It felt like everyone there spoke a language that I always knew but rarely had spoken back to me. It was a rare and profound reminder that community, safety, and understanding can change the way a chronically ill body feels because, to put it simply, I finally felt normal.

While I cannot speak for all of the attendees, I know that I felt this way for a variety of reasons, and I am going to try my best to put it into words.

For starters, I could tell that the conference itself was intentionally designed with us in mind, and that intention showed in every detail. Organizers checked-in on us often, encouraged rest, and made it clear that nothing was mandatory. They understood that rest is both a need and a responsibility. They understood that pushing too hard could cause flare ups, particularly for those of us with IBD or conditions that involve fatigue, pain, and unpredictable symptoms. Even travel was supported as I received reminders and check-ins to make sure that I made it to my flight safely. This took the emotional labor out of the small things that usually drain me, and their help and accommodations were never made to feel like favors. Plus, everything was optional, yet everything was thoughtfully provided. It was all offered with genuine care, and that is something that I rarely feel in spaces outside the chronic illness community. I truly felt taken care of at every moment. I never felt pressured to show up to an event, and I never felt like a burden or a "waste of an attendee" if I did not. I felt valued simply because of who I am, IBD and all. Typically, I am made to feel as though my IBD devalues me throughout many domains of life, but I felt the opposite way while at HealtheVoices. I also felt considered and looked out for without being pitied or restricted. In other words, I felt empowered to take care of myself and to be the advocate I want to be, while also realizing that there is power in accepting help and care—there is the "power of us."

Regarding this "power of us," I was able to witness and experience how chronic illness can foster unity, even when diagnoses and symptoms may differ. This was exhibited right off-the-bat at the very first dinner of the conference when attendees were grouped based on their health condition, and I accidentally sat with the mental health and pulmonary hypertension group instead of the immunology group. What started as an awkward mistake due to my brain fog after a long day of traveling ended up turning into a gift. At this dinner, I connected with people who understood my mental health story in ways that felt grounding and familiar. Some even worked in the mental health field like I do, which felt incredibly validating. Therefore, even though not a single individual there had IBD, our emotional landscapes were still strikingly similar. We each shared our stories of career challenges, burnout, medical dismissal, discrimination, chronic pain, hospital admissions, fatigue, chosen family, the exhaustion of being misunderstood, and the emotional toll of navigating life and relationships with an unpredictable body and/or mind. We also connected over experiences specific to gender, such as being dismissed in medical settings until a male caregiver shows up.

These discussions reminded me that chronic illness is not defined only by biology. It is shaped by stigma, gender, identity, socioeconomic realities, and the emotional toll of constantly having to justify our experiences. Even people whose conditions had nothing in common with mine understood the same nuances of fatigue, pain, fear, and perseverance. Our hearts carried extremely similar stories, and the overlap was both comforting and heart-wrenching at the same time.

After that realization, I made a conscious effort for the rest of the weekend to approach people without looking at their badges. I did not want to lead with diagnoses anymore since I understood that a diagnosis was not the only thing that could foster deep connections. I wanted to understand people for who they were rather than for what condition they advocated for, even though I understood that advocacy often played a large role in the attendees' identities.

Despite it being an advocacy conference, my goal was not to advocate or educate that weekend. I simply wanted honest connection. I wanted to feel safe being myself. I wanted to meet people who would understand both the heaviness and the humor that come with living in a body that needs extra care and requires constant negotiation, without limiting myself by my diagnosis. My IBD has limited me enough already, and I was not going to let it stop me from making the meaningful connections that I have been seeking just because of a label. As it is, living with IBD and mental health challenges is incredibly isolating, especially when daily experiences and honesty are treated as oversharing. Everyone, including myself, preaches vulnerability, but it is difficult to be vulnerable when people do not know how to respond or cannot relate to your daily reality. That is why having the space to openly share about your day-to-day life—without the sugarcoating—is essential, and I found that space with each and every attendee carrying all of the diagnoses under the sun. It did not matter if they had IBD, a different chronic illness, or if they were a caregiver since we could all relate to one another in some way.

This was an incredible phenomenon that attendees and I noticed since at HealtheVoices, we did not have to explain the basics. Each conversation started with an innate understanding of one another. This understanding was not just based in compassion and shared experiences as it was oftentimes also based in shared medical knowledge/terminology, tips and tricks for navigating the healthcare system, etc. This is because everyone there lived some version of the same complexity. For example, many of the attendees understood Prednisone's mental and emotional side effects, sometimes even making light of it nonchalantly during conversations. Outside of the chronic illness space, these jokes and statements would have to be explained or given some background information, which can become exhausting over time, especially as you meet more people throughout your life. Having people who just "get" certain things—without needing to pause the conversation to explain and without having to worry about how it might be taken—is a breath of fresh air.

I did not have to soften the truth or worry about being labeled as "dramatic" or "negative." I did not have to explain why I left an event early or arrived late, nor did I have to explain why I did not finish the food on my plate. People just got it. This conference felt like a safe haven where I did not have to justify my needs or my existence as someone living with IBD. Even when we were not familiar with aspects of each other's health condition(s), we approached one another with curiosity rather than making assumptions, offering unsolicited medical advice or "natural remedies" that we have likely already tried/been advised to try countless times, or making remarks along the lines of, "everything happens for a reason" and "at least it's not cancer."

Conversations were honest but never forced, and I found that our weekend did not revolve entirely around illness. Sure, we cried a lot, but we also laughed a lot. We talked about hobbies, goals, spirituality, tarot, and things that were not centered in our diagnoses. It felt balanced in a way that my everyday life rarely does since either my whole world feels tied to my IBD, or I attempt to live in denial of its existence. At HealtheVoices, I did not have to shrink or edit my truth.

Yet, there was a moment very early into the weekend when I felt myself growing emotionally tired. While there were those intriguing conversations outside of chronic illness, most conversations were still deep and personal in nature. As a result, I felt an unexpected countertransference building inside of me, as if I had automatically tried to become the "listener" and "helper." Hearing such heavy stories that mirrored my own felt draining at first because I empathized deeply, and I wanted to hold people's burdens for them for as long as I could. That is what I am used to doing for others, and that is what I honestly enjoy doing. I see it as a privilege to be trusted with such personal information and stories of deep pain. Thus, I wanted to show my gratitude for this privilege, which expressed itself as me unconsciously attempting to relieve some of their burdens. It was as if I had naturally tried to step into the role of "therapist" instead of simply being myself. It is a habit that comes naturally to me, especially since I am entering the mental health field as a therapist and hope to work with people who have chronic illnesses.

I also initially experienced some imposter syndrome early into the conference. I was surrounded by these incredible advocates, many of whom have been advocating for decades. Some were even making a career out of their advocacy journeys. Even though it feels like IBD has been a part of my identity for my whole life, I was only diagnosed 4.5 years ago. Similarly, even though I feel as though I have been advocating for years, I really have only been actively advocating and becoming involved in the IBD community this past year. This made me begin to question why I was selected to attend the conference. What the heck do I have to offer? The more this question weighed on me, the more I felt the need to make up for my perceived lack of experience. This translated into my attempt to take on that therapeutic role that is all too comfortable because at least I would be offering something.

After a good night's rest that day, I realized something important: I was not there to fix anything, lighten anyone's burden, or carry emotional weight/pain for others. I was there as Michelle, not as a therapist. In fact, nobody there asked or wanted me to show up as a therapist. The fact that I was selected to attend the conference is proof in itself that there is something that I could offer within the advocacy space, even if I am a "newbie." There is something that I could offer by simply being myself, and I was allowed to be myself (whoever that is). Listening deeply is part of who I am, but absorbing others' pain does not have to be. Once I gave myself permission to let go of the helper role and the imposter syndrome while understanding that I could be present without absorbing everything, something inside of me shifted: I started to share and listen without performing emotional labor.

As a result, my body felt lighter. My energy felt different. As someone who lives with IBD and chronic fatigue as a constant companion, I hardly ever feel energized. Yet in that space, surrounded by community and safety, I felt more awake and alive than I have in years. I slept through the night without restlessness or insomnia, and I rested without guilt. That establishment of safety ultimately allowed my body to shift out of survival mode, which is the foundation of many evidence-based theories. I felt at home in a way I did not expect. I finally saw that I was allowed to accept help and let people in, even if they were going through their own struggles. I saw how support can be mutual and balanced. I also saw how I could be the "supported" instead of the "supporter," especially by how the HealtheVoices organizers took care of me without requiring anything in return. Letting myself step into that truth felt like exhaling after years of holding my breath. It felt like the relief that comes from finally unclenching my fists and jaw. It reminded me how much chronic illness is affected by environment and emotional safety because healing is not only medical, but it is also emotional and communal.

Overall, this experience made me realize how rare it is to just feel safe in everyday life. At HealtheVoices, everyone had something, whether it was a chronic illness, a disability, or the role of being a caregiver. Illness was not the exception. Rather, illness was the normal. By that, I mean that caregivers and those with health challenges were not the minority, and we did not feel out of place. That shift in perspective changed how I saw myself as it made me feel entirely human. Despite my symptoms persisting due to their chronic nature, I did not necessarily feel "disabled." I did not feel "different" or "abnormal." I did not feel like my everyday reality was "too heavy" or "too personal" to be shared. It was simply life, and almost everyone there understood.

The environment created at HealtheVoices highlighted a crucial truth: the world can accommodate people living with chronic illness, but spaces simply choose not to. The conference gathered people with vastly different conditions and needs, and yet everyone I met felt included and supported. This was not magic. This was intention. This was care. This was a commitment to treating people with chronic illness as fully human. I felt that my needs mattered and that I mattered. The organizers did not treat accommodations as burdens but rather as standard practice. This was eye opening because many institutions act as if inclusion is too much work, but this conference proved that it is entirely possible. In fact, it showed me that inclusion is completely achievable when people genuinely want to create it. To put it simply, inclusion is a choice. Dismissing people is also a choice. Institutions, workplaces, and communities can make room for us, but they simply choose not to invest in the effort.

I left the conference with a heart full of gratitude for the connections I made, the stories I heard, the jokes I shared, the insights I gained, and the revitalized sense of identity that I fostered. I left with a deeper understanding of caregiver burden and the emotional landscapes of people living with all types of conditions. I left with the lived experience of how community is essential for healing. I left with a reminder to show up authentically, even in spaces that do not always understand. I left with a deeper commitment to advocate for people with IBD and for people living with chronic illness(es) more broadly. I laughed more than I expected to, and I actually felt real joy. I left with the realization that I often carry emotional burdens for others and take on roles that are not mine to hold, and that realization is going to guide how I move forward in my personal and professional life.

Most of all, I left with a renewed determination to push for environments that truly include people with IBD and other chronic conditions. We deserve to feel normal, included, and valued. We are not abnormal. We are simply made to feel that way by systems that refuse to accommodate us. Anyone can become disabled at any time through illness, accident, age, etc. Anyone can become sick. Anyone can get hurt. Everyone ages (or at least that is the end goal). It is easy to not be concerned about something that does not affect you, but take it from me, it is 100% possible to wake up sick one morning and never be able-bodied again. That is the story of many people with IBD and many people with chronic illnesses. Inclusion matters because disability affects all of us eventually. Anyone can shift into the world that I navigate every day. In turn, inclusion genuinely benefits everyone.

All in all, HealtheVoices reminded me that despite my IBD, I am not alone—I never was. It reminded me that there are some spaces where people like me can feel completely safe, completely understood, and completely ourselves. There are places in the world where people with IBD can feel completely and beautifully at home. Being in such a space where chronic illness and disability is the norm shifted my understanding of what it means to feel "normal." It showed me what true accommodation, accessibility, community, and compassion look like. It showed me what is possible when people choose care over convenience. It proved to me that inclusion is not only possible, but it is deeply worthwhile. I will carry that truth with me and continue advocating for a world that chooses to see us, support us, and welcome us as we are. And for that, I will be forever grateful.