By Varada Srivastava (India)

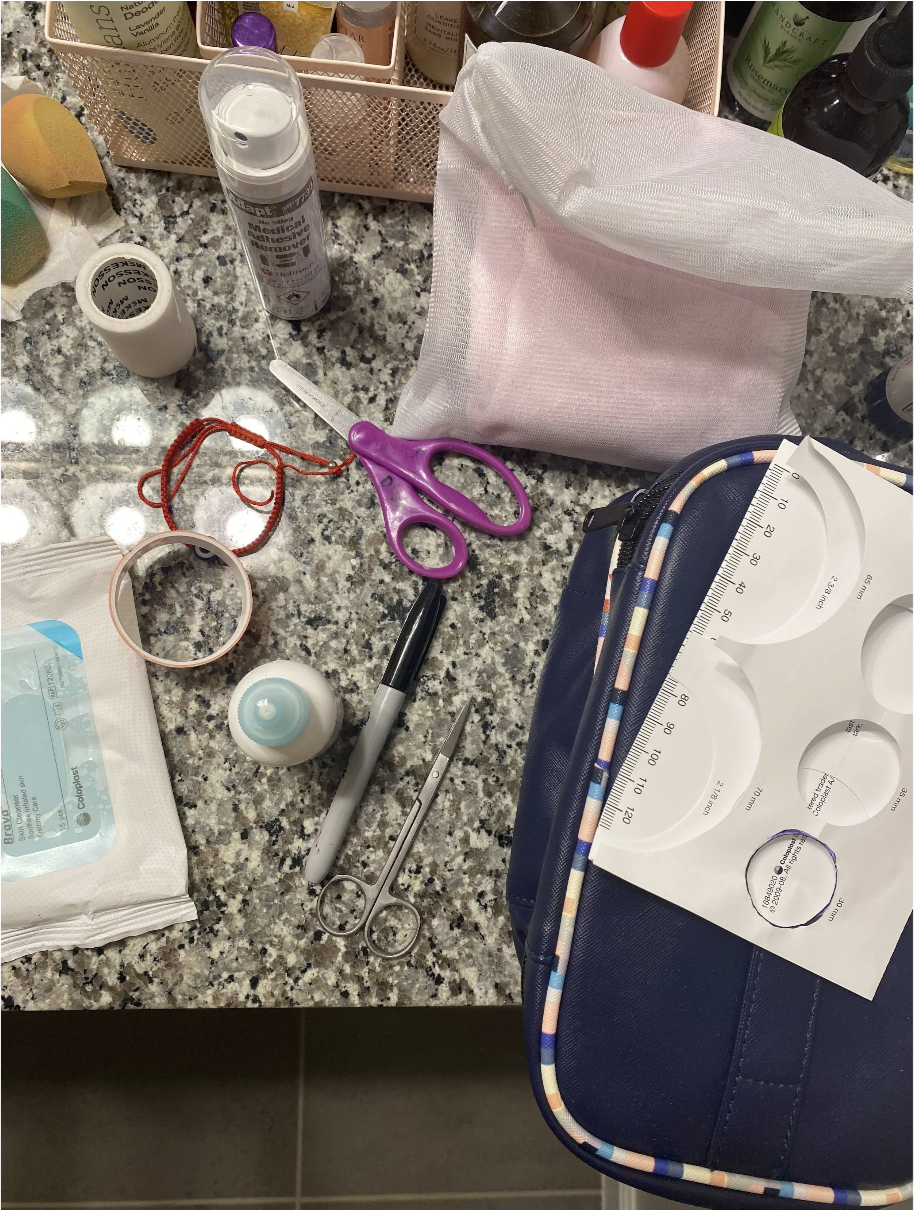

Hanging out with friends, attending parties, going to school are all things kids with Crohn's disease lose out on. You’re hospitalized or too sick to get out of bed many times, especially during the beginning stages of diagnosis. Not to mention the mental health issues that come with dealing with a chronic illness from a young age - anxiety, depression, PTSD associated with hospitalization are all too common. It can be very difficult to maintain friendships when you’re trying to survive daily life. How people react to your chronic illness is one of the pivotal points of friendship. I couldn't help but notice a pattern between the friendships I’ve maintained over the years. The common factor between them has been my friends’ ability to listen and not give unsolicited advice when I am talking about my disease. This is a quality I personally look for, however I have heard from many of my other friends who have a chronic illness that this is something they appreciate as well.

As someone who has been living with this illness for more than 6 years now, I have received my fair share of undesired advice from family, friends and random strangers. It is something that really aggravates me. Getting advice when you're trying to rant is pretty annoying in general but when you add IBD - something that is a very personal and a sensitive topic - the reaction you get can be explosive. Living with a chronic illness is tricky, most of us have figured out what works for us whether it's medicine or food after a long and painful journey. And as young adults, most of that journey is still left. One of the main reasons why some of us have such a negative reaction towards this is because it comes across as insensitive and like a privileged view on something very complicated.

This however, doesn’t mean that you don't look out for your friends with IBD. One of the foundations of a good friendship is caring for and helping out your friends. If you are a loved one of someone who suffers from a chronic illness, ironically, this is the advice I would give you:

1

Ask your friend whether this is something they are comfortable talking about. Never push them to talk about their diagnosis, medicines or journey.

2

Don't take it personally if this is something they would like to keep private. Many of us have gone through very difficult diagnosis journeys and talking about them can bring back a lot of trauma.

3

Research about the condition. Try to understand where your friend is coming from and what they struggle with on a daily basis.

4

Try not to give unsolicited advice, but do intervene if you notice them doing something that may not be in their best interest.

Having a good support system is extremely important for someone with a chronic illness. Friends give us a safe space to express and explore our emotions. Friends are, in reality, the best emotional medicine for people like us to overcome sadness and motivate us to take a leap of faith to transform our lives for the better.

Photo by Helena Lopes from Pexels.