That last part no one says out loud, but I can fill in the blanks. After all, this is a fairly representative template of how these conversations tend to go. Somewhere between awkwardness, disbelief, and my personal favourite, curiosity, lives disclosure – a process that is central to forming and maintaining relationships (Willems et al., 2020).

So if you want to progress from stranger to friend, or just have more honest conversations with your friends, lover(s), or family, preferably with a [wry] sense of humour about missing organs, here is a list I created. It’s a list of organs, not including limbs and sensory organs, that can be removed from the human body that would still allow someone to survive with a fairly decent quality of life.

“Decent” quality of life is, of course, a subjective statement. For our present purposes, let’s define it to be that most people who have had this organ removed and fully recovered from the surgery are able to have a fairly independent life, including performing essential daily personal and professional tasks and maintaining social relationships.

It’s a fairly morbid list. Most of the information comes from my own knowledge on the subject gathered through readings and discussions, though I fact-checked details on the Mayo Clinic website.

Without further ado, here’s the list of 12 organs that you could probably survive without:

#1 Appendix.

If you have appendicitis, in which your appendix becomes inflamed, enlarges, and can even burst, then your appendix may be removed by performing an appendectomy. Since the removal of the appendix did not seem to lead to noticeable adverse effects for most people, it has been traditionally thought of as a vestigial organ, although increasing research suggests that the appendix plays an immunoprotective role.

#2 Tonsils, including adenoid tonsils.

If you have tonsillitis, in which the tonsils become infected and swollen, your tonsils can be removed during a tonsillectomy. This used to be a common childhood procedure, but given the role of tonsils in preventing pathogens from entering the body and other medical considerations, non-surgical interventions for tonsillitis are increasingly preferred.

#3 Thyroid.

If you have the unfortunate diagnosis of thyroid cancer or dysfunction, such as goiters or hyperthyroidism, a thyroidectomy may be performed. If partially removed, your thyroid may still function normally. However, following a total thyroidectomy, you would require daily hormonal replacement therapy, given the crucial role of the thyroid gland in producing hormones essential for metabolism, growth, and development.

Digestive Organs

#4 Colon / Large intestine.

Your colon may develop cancerous polyps or inflammation due to diseases such as Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. During a colectomy surgery, to get rid of this cancerous or highly inflamed bowel tissue, your large intestine may be partially or totally removed.

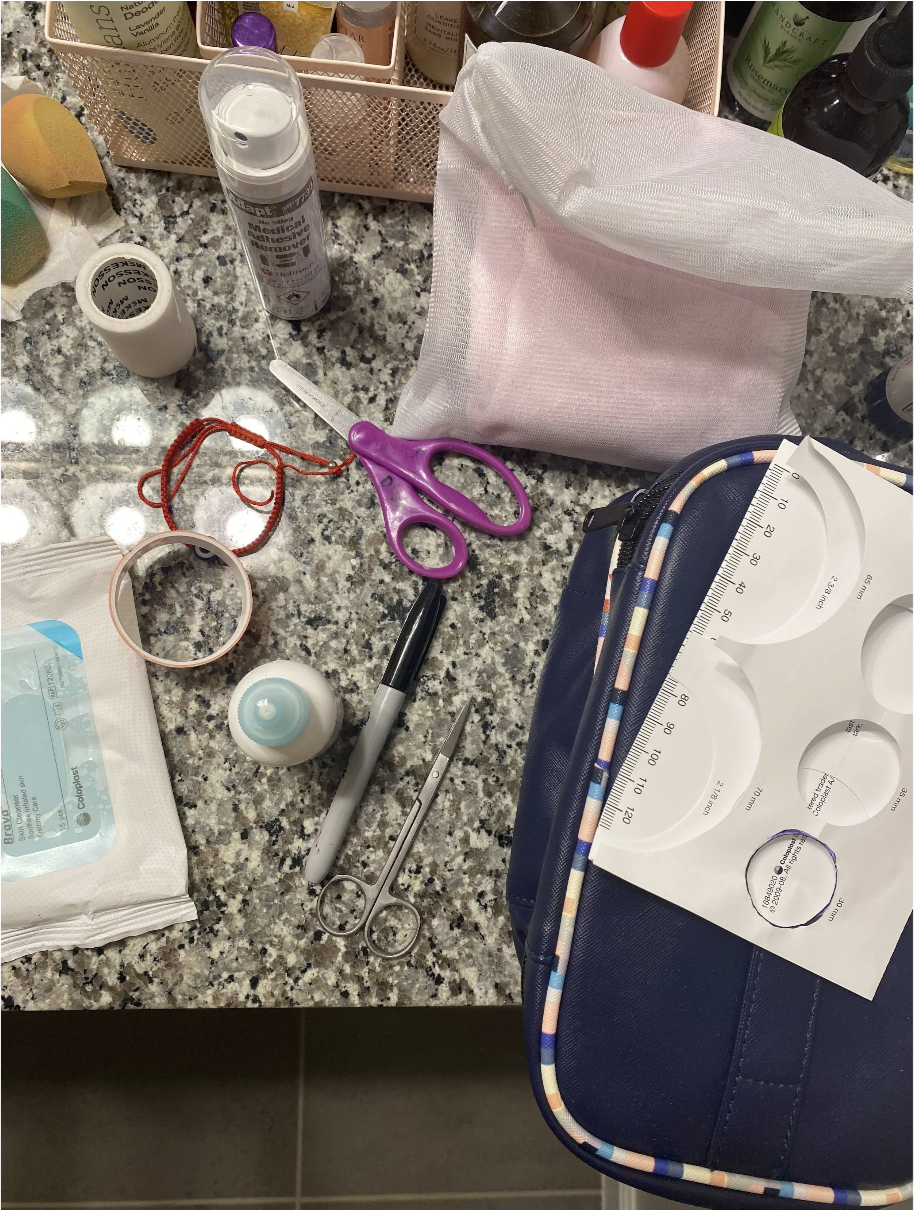

The remaining colon or small intestine may be diverted towards the abdominal wall to allow faecal matter to safely and easily leave the body through an opening on the belly called a stoma. This is an ileostomy, and people with stomas often refer to themselves as “ostomates.” The ostomy bag must be emptied every few hours and changed every few days for the individual to live comfortably.

Alternatively, the remaining intestinal tissue can be restructured to form an internal J-pouch where faecal matter is collected and then passed through the rectum. Unlike an ileostomy, in this case, no medical aids like the ostomy pouch are required.

#5 Rectum.

Depending on the presence of diseased tissue due to rectal cancer or if intestinal inflammation spreads into the rectum, a proctectomy can be performed to remove all or part of your rectum. People with total proctectomies may refer to themselves as “having a barbie butt,” hinting at the lack of an anal opening just like a doll. In this case, they would also rely on an ostomy bag for daily functioning.

#6 Gallbladder.

A cholecystectomy can be performed to remove your gallbladder if complications or cancer resulting from the presence of gallstones, polyps, or inflammation is detected. Most people recover from cholecystectomies with little or no digestion issues. Since the gallbladder is responsible for storing bile, a fluid that helps your digestive system break down food, in the case of digestive issues, this can be managed through dietary and lifestyle choices or medication.

#7 Spleen.

Following trauma, infection, cancer, or blood disorders, your spleen can become inflamed, enlarge, or rupture. In this case, a splenectomy is performed to remove this organ. Since the spleen plays immune functions like red blood cell filtration, following surgery, some individuals may be more prone to infections and would require specific vaccinations or medications.

#8 Stomach.

There are many types of bariatric surgery that you can undergo. Some surgeries address trauma to the stomach or cancer. Other surgeries are for weight-related health issues where non-surgical interventions have not been sufficiently effective, and the issues are life-threatening (e.g. can lead to cardiac arrest). The stomach can be partially or fully removed, and the stomach can be partially or fully bypassed when connecting the oesophagus (food pipe) to the small intestine. Following surgical recovery, your quality of life can be managed through dietary and lifestyle choices.

Urinary Organs

#9 Kidneys.

A nephrectomy can be performed to remove you kidney, typically for organ donation, in which the recipient has failed kidneys and may even rely on dialysis for kidney function. While you can technically survive without both kidneys, because the kidneys provide an essential function of blood filtration (resulting in urine production), you would need ongoing dialysis, which is an intensive procedure that can highly compromise quality of life.

#10 Bladder.

In the presence of cancer, or of development or neurological or inflammatory disorders of the urinary system, a cystectomy can be performed to remove your bladder. The details of the cystectomy vary depending on the spread of disease; for example, reproductive organs may also be removed. In the absence of the bladder, a urinary diversion is created so that urine can safely and easily leave the body through an opening on the belly, called a stoma. This is a urostomy, and people with stomas often refer to themselves as “ostomates.” The urostomy bag must be emptied every few hours and changed every few days for the individual to live comfortably.

Reproductive Organs

#11 Testicles / Testes.

In the event of testicular cancer or trauma, an orchiectomy may be performed to remove your testicles. While most people can return to a good quality of life following full surgical recovery, the individual would be unable to conceive and may also experience sexual dysfunction. Given the role of the testicles in producing testosterone, hormonal replacement therapy following surgical recovery is increasingly recommended to prevent long term adverse outcomes.

#12 Ovaries and Uterus.

Following cancer, trauma, conditions such as endometriosis, or for reproductive control (particularly in areas of the world where menstrual care and contraceptive options are limited), an oophorectomy to remove one or both of your ovaries and/or a hysterectomy to remove your uterus may be performed. Following surgical recovery, the individual would be unable to conceive. While most people can return to a good quality of life following surgical recovery, given the role of the female reproductive organs in producing oestrogen and progesterone, hormonal replacement therapy is increasingly recommended to prevent long term adverse outcomes.

Featured photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels.