NEWS

Internalized stigma in IBD, mental health, and quality of life: A study review

by Aiswarya Asokan (South India)

Living with IBD comes with a lot of constraints that no one prepares you for. Every time one goes through a major life transition like starting college, joining work, or getting into a relationship, adapting to the changes is never easy. It’s often difficult to fit in due to our IBD, which in turn puts us under a lot of stress and anxiety. Research indicates that bowel-related issues are a widespread cultural taboo and historically, IBD has been seen as “psychosomatic,” further stigmatizing the condition.

To learn more about this, I read a paper titled “The mediating role of psychological inflexibility on internalised stigma and patient outcomes in a sample of adults with inflammatory bowel disease.” This study was conducted to examine the relationship between ‘psychological inflexibility’ (when someone struggles to adapt to challenges, avoiding emotions or feels stuck) and ‘internalized stigma’ (when individuals adopt negative societal beliefs or shame as their own, and devalue their identity) on health outcomes. The authors looked at outcomes like mental distress (depression, anxiety, stress), health related quality of life, self-efficacy, self-concealment (hiding personal information that is distressing or negative from others), beliefs about emotions, and fatigue (physical and mental) in adults with IBD using an online survey of 382 participants.

This study suggested that:

Adults with IBD who had higher rates of psychological inflexibility also had higher rates of internalized stigma, negative beliefs about their emotions, self-concealment, mental distress, fatigue, and impaired quality of life.

Psychological inflexibility was inversely related to committed action, stigma resistance, and IBD self-efficacy.

Adults with IBD who had higher rates of internalized stigma also showed higher rates of mental distress, self concealment, negative beliefs about their emotions, fatigue, and poor health-related quality of life.

Internalized stigma was inversely correlated to stigma resistance, IBD related self-efficacy, and committed action.

Participant’s age and educational level showed an inverse correlation with their psychological inflexibility. Their IBD severity (in the past 3 months), the presence of an ostomy, and their COVID-19 self-isolation status were positively correlated.

Internalized stigma was higher for individuals with an ostomy, those currently taking steroids, who had experienced severe IBD in the past 3 months, and who were more self-isolated, whereas educational level was inversely correlated.

Other interesting insights from this study:

Individuals who face discrimination regarding their IBD, who are less able to employ ‘flexible’ responses may spend more energy avoiding stigmatizing experiences, making it harder for them to engage in meaningful activities.

New research indicates that general familiarity with IBD can help reduce public stigma; highlighting the importance of IBD awareness campaigns to increase public understanding of IBD, thereby reducing stigma.

These study findings suggest that lower levels of internalized stigma is associated with increased psychological flexibility and better patient outcomes. Modalities of therapy like ‘Acceptance and Commitment Therapy’ (ACT) – which aim to increase psychological flexibility by changing individuals’ relationship with their thoughts, feelings and behaviors – may be a helpful intervention.

Personally, years of living with IBD have enabled me to build a circle of people where I can take my armor off. But still, going through repeated flares, body image issues, breaks from education, social isolation, and being under steroids takes a toll on my mental health and quality of living. Often the medical team's support stops once your blood counts are under control, leaving us with the responsibility of picking up ourselves and moving on with the new normal.

Citation:

Reynolds DP, Chalder T, Henderson C. The mediating role of psychological inflexibility on internalised stigma and patient outcomes in a sample of adults with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2025 Apr 1:. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaf055. Epub ahead of print. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40168103/

Photo from “Total Shape” on Unsplash.

Life with Crohn’s – A Pantoum

by Alexis Gomez (California, U.S.A.)

This is your life now.

The burning and belly aches

instigated by none other than Crohn’s,

your forever counterpart.

The burning and belly aches,

the appointments, calls, meds, side effects.

Your forever counterparts are

memories of you in both sickness and health.

The appointments, calls, meds, side effects

force you to advocate for yourself like never before.

Memories of you in both sickness and health

remind you how quickly life can change.

You’re forced to advocate for yourself like never before but

it makes you stronger.

You’re reminded how quickly life can change,

how the world doesn’t pause when you need it to.

It makes you stronger–

the moments of grief and relief.

The world doesn’t pause when you need it to, but

you can savor times of joy and give yourself grace.

The moments of grief and relief

are ever-present with IBD.

You can savor times of joy and give yourself grace.

You deserve it because

this is your life now.

What It’s Like Working Through Phobias: Creating A Comfort Toolkit

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

I can't remember a time when I didn't have a blood/needle/medical phobia. I would regularly faint at the doctor's office and even talking about blood was enough to make me pass out in high school. It wasn't a problem until I developed chronic stomach issues and was diagnosed with microscopic colitis. All of the sudden, I was pushed headfirst into a world of doctors' appointments and countless medical tests. It's hard enough to find answers from doctors, but fear can make you ignore your problems, making things worse. I still struggle with this phobia today, but with the help of a therapist, I’m working through my issues. Please seek the help of a trained professional to face your phobias in the safest way possible. Here are several strategies I'm using to make progress facing my fears.

Desensitization Training/ Exposure Therapy

Desensitization and exposure therapy can start with looking at images of videos of your phobia, eventually progressing to more realistic scenarios. For instance, someone with a blood phobia might progress from viewing images to medical shows and eventually going to blood drives. The overall goal might be to get bloodwork done, but you have to build up exposure over time to get more comfortable with your fears.

I've been unknowingly trying to do this my whole life. As a kid, I would reread veterinary books to expose myself to a little literary medical gore. I would deem it a success if I didn't get woozy. Today, medical imagery has become an inherent part of my artistic practice. I find exposure more palatable if I attempt to explore images and procedures from a place of curiosity rather than fear. If I'm looking at veins, I try to ask myself what colors I see under the skin. I've progressed to the point where I can look at surgical photos of arteries and attempt to draw them without getting queasy. It's easier for me to separate myself from a picture than a procedure happening to me, so that's where my exposure therapy has started.

Working with a therapist, I did a deep dive on my phobias and my hierarchy of fears. Instead of just seeing all situations surrounding blood or needles as being equally terrifying, I was able to sort them into a list of situations with varying intensity. While younger me thought a finger prick was the worst situation possible, I now list it much lower on my list, opting to put IVs in a higher position. It's all a matter of perspective. By making a fear hierarchy, I was able to tackle lower intensity situations and gain confidence and resilience before braving my top fears.

Keeping A Sense Of Control

When I was little, my family had to trick me to get me in the doctor's office. In adulthood, I tried to mimic this strategy by being spontaneous. Instead of scheduling a flu shot and worrying about it for weeks in advance, I'd wake up and decide to go that morning. This strategy somewhat lessened my stress, but it also felt too hurried. I never had a sense of control, just urgency to get it done and over with. It didn't leave me in a good headspace and I still found myself fretting over the possibility of getting a shot for weeks ahead of time.

Now, I'm better prepared. With the help of my therapist and journaling, I've made lists of what is within my control during doctors’ appointments. I keep a “comfort bag" ready and always bring it with me to appointments. If I need blood work, I pack my own snacks for afterwards and plan to reward myself with a sweet treat from a nearby cafe. I also pick out my "victim” arm ahead of time based on which arm feels stronger than day.

When it's my turn for bloodwork, I tell my nurse right away that I'm terrified and I'm a faint-risk. I also ask for the reclining chair when possible. It's not so upright that I'll get dizzy and slump over, but through experience, I've also found that fully lying down feels more vulnerable and heightens my fear. A reclining chair puts me in a better headspace, so it is important that I advocate for my preferences. Doing small things consistently and giving yourself small choices in your healthcare can help you feel more in control and you'll know exactly what to expect.

Pack A Comfort Bag, Activate Your Senses

In an effort to ground myself, I try to pack things in my bag that activate my 5 senses of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. I always have these items in a bag and ready to go. Consistency is key, so I bring them with me to all of my medical appointments. When I’m in the waiting room, I grab my headphones and put on some music. I also pack sensory items that are calming like fidget toys to distract myself with. If I’m getting blood drawn, I have a tennis ball handy that I can grip, tissues for when I cry, and a snack for when it’s all over. This kit can be any size and it should be personal to you. Here’s a list of what I keep in my bag:

Snacks

Water

Tissues

Tennis ball (to grip)

Lavender essential oil

Hand warmer

Electrolytes packet

Fidget toy or comfort object (worry stone)

Headphones for calming music or ASMR

Don't Just Wing It, Strategize

Plan out your day ahead of time. Plan to have downtime afterwards to chill, recover, and reward yourself. I like to have a friend or family member drive me to and from appointments just in case I feel dizzy afterwards.

Pressure therapies or tense & release exercises have also been proven to help calm the body. Box breathing is another exercise to keep in your toolkit. It can stop you from hyperventilating and keep you calm. Make sure to try these techniques out BEFORE an appointment or exposure to your phobia. Practice makes perfect and not every therapy works for every person. Find what fits you and make a plan to tackle your phobias.

God of Small Things, Arundhati & THE LOVE EQUATION - A Crohn’s View

by Rifa Tusnia Mona (Dhaka, Bangladesh)

Stigmas Have Power! You might wonder why I say this as an IBD advocate. After all, stigmas are often baseless and untrue. But when they come at you from all directions—constantly, persistently—they start to wear you down. That’s when the real distraction, aka destruction, begins.

Imagine this:

One morning, you wake up feeling like something is coiling and twisting inside your stomach. You can’t eat. Or if you do, your body refuses to digest. Nausea takes over. You vomit again and again. The cramps hit without warning, stabbing, vanishing, then returning like waves from a storm. You feel trapped in a body that’s turning against you.

At first, people think it’s temporary—just a bug, maybe food poisoning. But then, something changes. The concern fades, and in its place, they start labeling you.

One morning, your mother decides to take you to church. If you’re Muslim, maybe it’s a hujur or a Sufi healer. Neighbors drop by. They don’t bring comfort; they bring unsolicited advice. "Have you tried this doctor?" "You should pray more."

Later, one morning, you find yourself lying in a hospital bed. A nurse enters and says, “Ask God for forgiveness.”

It hits differently. You’re not just battling a disease anymore—you’re battling judgment.

That’s the thing about stigmas: they’re powerful because they echo from everywhere. Different mouths, same message. And it always seems to come when you’re at your weakest.

But the hardest part?

When it comes from the people you love—your friends, your family—the ones who’ve always stood by you. That’s when the real confusion begins. You think, They care about me. They’ve never meant me harm. So maybe… maybe they’re right?

And just like that, you start to question yourself—not your illness, but your worth.

It took me a long time to realize that human minds are incredibly complex. I used to carry the weight of every cruel word, every dismissive act, thinking I must’ve done something to deserve it. But over time, I began to understand: most of the time, it’s not about me.

People don’t always act from a place of clarity or kindness. Sometimes, they hurt others to soothe an old scar within themselves. Sometimes, they mirror the pain they once suffered. And sometimes, they hurt simply because they don’t know how not to.

That’s when it hit me—pain is transferable.

It doesn’t just live in one person; it moves, it multiplies, it morphs into behaviors, into beliefs, into judgment. And many of those who hurt us are, in fact, carrying unresolved pain of their own.

“The God of Small Things” by Arundhati Roy feels like a masterpiece to me—layered, lyrical, and hauntingly beautiful. But if I had to pick one part that truly stayed with me, it would be the part about what Roy calls ‘The Love Laws’—or, as I like to think of it, the unspoken equation of love.

“That it really began in the days when the Love Laws were made. The Laws that lay down who should be loved, and how, And how much.”

-Page 33, Chapter 1, Paradise Pickles and Preserves, The God of Small Things

According to this idea, the amount of love we receive can sometimes feel predetermined—set by invisible rules we never agreed to. From Arundhati Roy’s words, I understood that love is often measured through two things: care and concern. These are the true units that define the depth of a relationship.

For love to feel genuine and meaningful, both must be present—together. When only one shows up, or when they're offered inconsistently, the relationship starts to feel imbalanced. It turns into something less whole, something we try to justify as "complicated" or label as, “Please, try to understand.” But deep down, we know—it’s a compromised connection.

“After Ammu died (after the last time she came back to Ayemenem, swollen with cortisone and a rattle in her chest that sounded like a faraway man shouting), Rahel drifted. From school to school. She spent her holidays in Ayemenem, largely ignored by Chacko and Mammachi (grown soft with sorrow, slumped in their bereavement like a pair of drunks in a toddy bar) and largely ignoring Baby Kochamma. In matters related to the raising of Rahel, Chacko and Mammachi tried, but couldn’t. They provided the care (food, clothes, fees), but withdrew the concern.”

-Page 15, Chapter 1, Paradise Pickles and Preserves, The God of Small Things.

There was a time when I was hospitalized for over a month. My father had a full-time job, and my mother had to juggle between caring for me and my younger sister. With both of them stretched thin, I reached out to every friend and relative I knew, hoping someone could step in as a caregiver. But no one came forward.

I was already battling an undiagnosed illness, and on top of that, navigating hospital departments alone, collecting test results while being so physically unwell—it felt like walking through fire. In that moment, a thought struck me hard: “After living over two decades, have I still not understood the love equation?”

Living with a chronic condition like Crohn’s has, in a strange way, been like being handed a special lens. I began to see certain relationships for what they truly were—fragile, one-sided, and built on illusions. That clarity gave me the strength to say “No” and walk away from connections that no longer served me.

It might sound harsh, but when your body is already carrying so much pain, the weight of empty relationships and unmet expectations becomes unbearable. Letting go became a form of relief, a way to breathe again. I’ve come to believe that sometimes, releasing old bonds opens up space for new, more meaningful ones. And life, quietly but surely, moves forward.

In a world where being "different" is often taboo, genuine relationships—the ones rooted in care and understanding—can feel like a warm shield. They make all the difference.

These are just my reflections, and as a reader, you’re welcome to hold your own. But thank you for making it this far—I appreciate your presence here, and I hope to meet you again in my next write-up.

Featured photo by Kaboompics.com from Pexels.

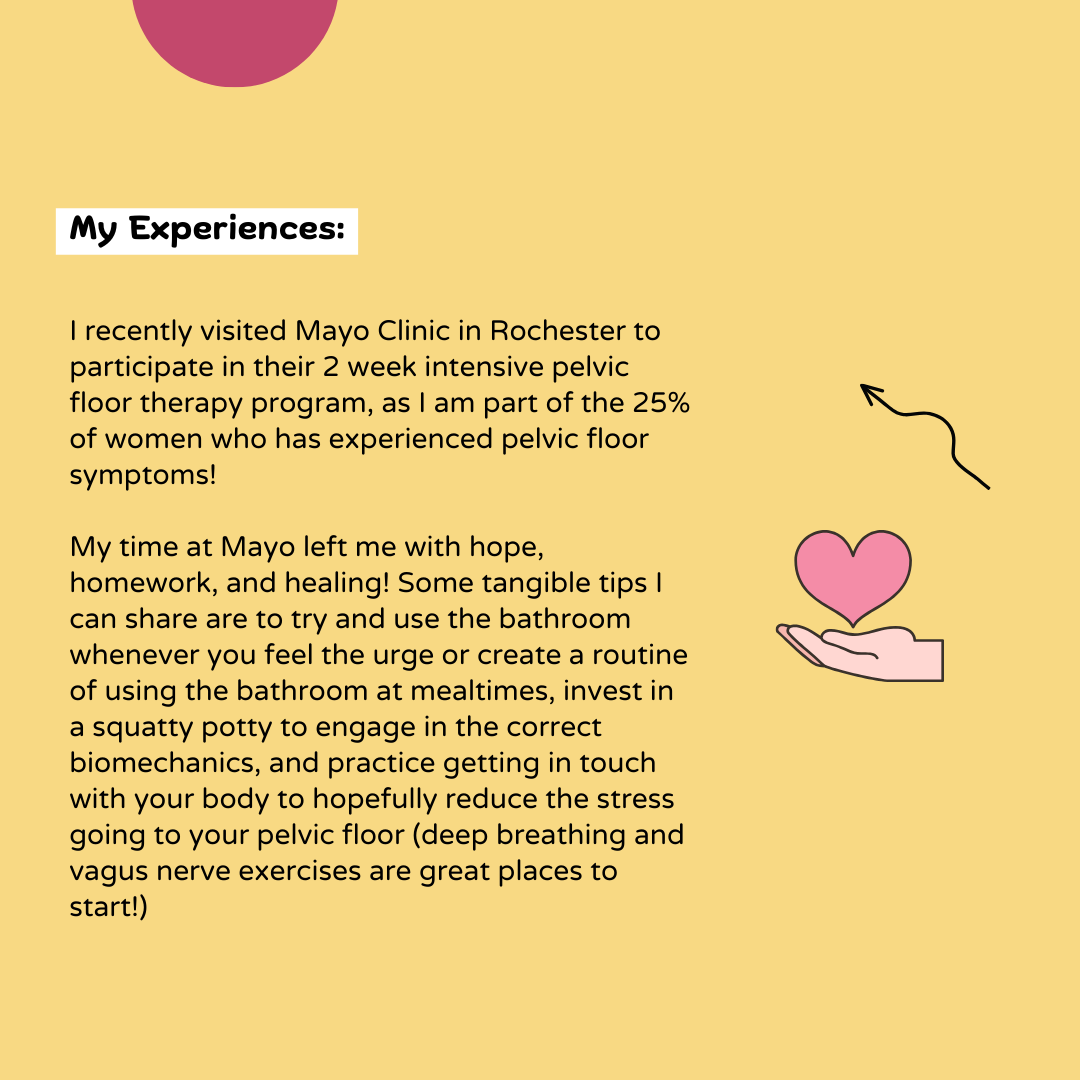

Pelvic Health and IBD: An Infographic

by Lexi Hanson (Missouri, U.S.A.)

Info from: https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/conditions-services/obgyn/urogynecology/pelvic-floor-disorders.

I am more than what you see: Living with IBD body changes

by Beamlak Alebel (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Living with inflammatory bowel disease, my body has changed in ways I didn't choose. People see my outward appearance and make assumptions. Often, they don't wait to hear your story, and they judge you based on your size or looks: no words, no chance. It hurts because words can't always express what we feel inside.

They don't see the battles I fight every single day. I’ve heard it all:

"You are too skinny."

"You don't look strong."

"You must not eat enough."

But I know myself - I am strong. My journey is filled with courage, healing and hope. I don't have to be judged by my size, I am more than that. My size doesn't define my strength, my resilience does.

I have faced many tough times, but people don't see me as a serious person because of my appearance. I have survived painful flare ups, countless hospital visits, difficult medication side effects, surgery, and emotional lows and that could have broken me.

And yet, I am still here: still standing, still fighting.

I may not have a body society views as "tough," but I carry strength in my spirit.

I carry it in my story.

Being judged by my body and appearance has been painful, but it has also taught me what really matters: my ability to rise again and again.

I am not a slab of meat to be consumed or judged. Your power lies in what you overcome, not in the size of your frame or your appearance. We are more than our bodies, we are warriors.

No one knows what tomorrow holds, and what we have today is not guaranteed. Life changes, and bodies change, but our worth remains. Let’s learn to see beyond appearance, and appreciate our strength. We never know the silent battles someone is fighting – behind every look, there is an untold story.

Photo by Unsplash.

Michelle’s IBD “Burn Book”

by Michelle Garber (California, U.S.A.)

Inspired by Mean Girls and high school yearbooks, I created an “IBD Burn Book” to shed light on the invisibility of IBD and emphasize the importance of empathy when interacting with someone with IBD.

When you first open the Burn Book, you’ll see that my “Mask” has been crowned Prom Queen. The images on this page are from moments when I had my mask on—when I pretended to be “fine.” The background words reflect how others perceive me more positively when I wear this mask, which is why it was elected Prom Queen.

The next page is a Student Feature of my Inner Thoughts. Here, I am without my mask. This contrast serves as a reminder that appearances can be deceiving—what you see on the outside isn’t always real; it might just be a mask.

Following that is a Not Hot List, which consists of a collection of phrases people should never say to someone with IBD. (Sadly, every one of these remarks has been said to me).

The final page of the Burn Book is a WANTED poster—for empathy. Instead of harmful comments, this page lists empathetic phrases one should say to someone with IBD. Essentially, it serves as the “Hot List” in Mean Girls or high school terminology.

———

Invisible illnesses come with their own set of challenges—such as a widespread lack of awareness—but the focus here is how easily someone with IBD can hide their struggles. Smiling through the pain, pretending to feel well—it becomes second nature. I’m not the first person to wear a “mask” to feel accepted or to make others comfortable, and I certainly won’t be the last.

The reality, though, is that IBD is a constant battle. Even if you see me dancing with friends, traveling, or enjoying a big meal, I am still struggling. The takeaway? You never truly know what someone else is going through, so always choose kindness. More importantly, choose empathy. If you do know what someone is going through (specifically IBD in this case), be especially mindful of your words and actions. While you might assume your words and actions don’t affect us, remember—we’ve had a lot of practice hiding our pain.

From Here to There

by Alexis Gomez (California, U.S.A.)

I am here

but sometimes I want to be at the point

where my body is still like

the photo from 2007 where I am four

laying on the living room carpet

holding my infant brother who’s drooling

and I am smiling and

I am healthy and

I have never known a life unlike this.

I am here.

Not like those

under a setting spring sun

warming their skin

unburned,

unlike

my insides

eyes

mouth

scalp

lungs

legs

heart

ego.

I will get there

when I can say thank you

to my body for fighting

(itself)

to keep me alive

everyday.

Timelines are unpredictable.

I know I will get there because

I think of the future

I think about being in it

laughing

singing

dancing

admiring

feeling

appreciating

living.

I am here

for now

but I will get there.

(Photo by Fallon Michael on Unsplash)

IBD and Grief

by Akhil Shridhar (Bengaluru, India)

Each person has a unique story when it comes to their experience of coming to terms and living with IBD. What I realized after speaking to some of the patients who have struggled with the disease for quite a few years is that there is a similar pattern in our response to this life-altering event. The diagnosis, which in itself is a drawn-out process of striking out every other possible disease of the gut to finally settle on one condition, which includes countless blood tests, scans, endoscopies, colonoscopies with biopsies, like any other chronic condition, is just the beginning. When I came across the commonly used description for the stages of grief, I couldn’t help but notice the similarities.

The stages of grief are commonly described using the Kübler-Ross model, which outlines five stages that people often go through when dealing with loss or significant change. These stages are not linear, meaning people may experience them in different orders or revisit certain stages multiple times. The stages are Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression and Acceptance. With our diagnosis of a chronic condition, we experience a profound shift in reality that can evoke similar responses:

Denial

Initially we struggle to accept the diagnosis, believing it to be a mistake or downplaying its seriousness. For most of us who are coming across IBD for the first time, usually without any family history, this sounds familiar. I would perhaps lean towards the latter, as a history of psoriasis, a similarly chronic condition, majorly influenced my decisions, which I would come to regret later.

Anger

As reality sinks in, we often have feelings of unfairness and frustration. This anger is usually targeted at our body, medical professions and, in most cases, our loved ones. I found myself feeling guilty of my circumstances, angry at the doctors for not understanding my concerns and addressing them, which feels ironic, and frustrated with my loved ones for downplaying the symptoms.

Bargaining

We then attempt to negotiate our way out of the situation, trying alternative treatments, lifestyle changes, or even stopping medications altogether. Due to my previous experience with psoriasis and other circumstances, I found myself slowly stopping medications. As expected, when the symptoms started flaring up again, I looked into alternative treatment that had shown good results for my psoriasis, a grave mistake which put me in the severe Crohn's category taking me years to recover from.

Depression

As we finally come to terms with the condition’s long-term implications, a sense of loss and hopelessness follows, leading to sadness, withdrawal, or a loss of motivation. Although with IBD being a disease of the gut, this just adds to the list of causes for depression for many of us.

Acceptance

Over time, we adapt and find ways to manage our condition and integrate it into our lives. We begin to accept the new normal and find strength and purpose in this new journey. Five years into this journey, I find myself here, a veteran I say to myself, with a new resolve to help others navigate theirs.

The emotional and psychological journey of adapting to a life-altering event closely resembles a grief-like path. Chronic conditions not only impact our physical health but also our identities, relationships, and goals, making the process of adjusting and coping essential. It's important to note that these stages are a framework, not a one-size-fits-all process. People grieve in unique ways, and other emotions like guilt, confusion, or relief might also play a role.

This is why advocacy can be an incredibly powerful tool to make a difference in helping individuals by providing awareness and education, building a resource network, or helping in accessing resources. It is also important that we encourage empathy and patience with caregivers, family members and society as a whole to provide the required support during these challenging times. For someone going through the journey, engaging in advocacy themselves can be transformative and empowering. On a larger scale, advocacy is also necessary for shaping policies and systems that lead to improved healthcare policies, workplace accommodations, or social programs.

I encourage everyone to seek help and, whenever possible, help out others, as getting diagnosed with IBD can be a deeply personal experience, but one should not be forced to navigate it alone.

(Image credit: marekuliasz from Getty Images)

Potential IBD Accommodations for Teachers and Students (from a NYS Teacher)

by Kaitlyn Niznik (New York, U.S.A.)

This infographic was created from discussions with other teachers in the United States living with IBD. Through those conversations, I realized that the workforce can be a scary and precarious place for people living with chronic illness. As a unionized, tenured teacher in a public school, I acknowledge I am in a privileged position to disclose my IBD. However, a teacher or student can choose not to divulge their chronic condition for a number of reasons including job instability or the fear of being singled out. I made half of my graphic focus on discreet ways to manage your IBD within the education system without revealing personal health information. This half includes having an emergency supply pack, trusted contacts that you can call for assistance, and knowing the location of private bathrooms instead of public stalls.

The other half of my picture illustrates ways a student with an IBD can pursue written accommodations to protect them at school. These include obtaining an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 Plan after their doctor writes a note confirming their diagnosis and its impact on the student's daily life. In the student's records, they would be classified under the "Other Health Impairment" category and this form would be reviewed and adapted annually. Parents, teachers, and district personnel would work together to create an IEP or 504 plan that supports the student's needs, helps them manage their illness, and works to reduce the student’s stress in an educational environment. Teachers with an IBD can also present a doctor’s note to their district to receive reasonable workplace accommodations.