“Don’t you have enough chronic illnesses?”

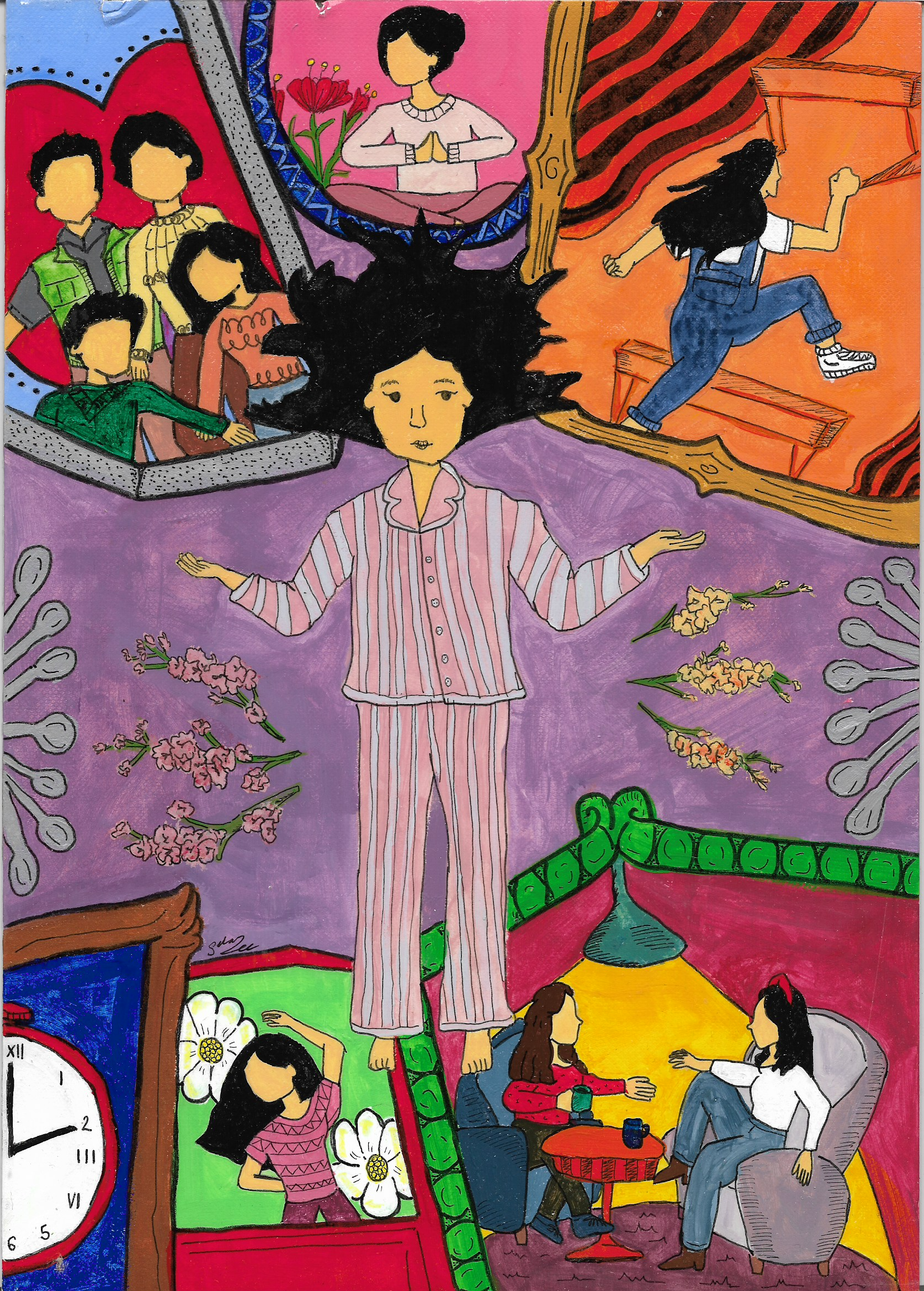

No one has actually ever asked me that before, but despite my efforts to push the question out of my mind, occasionally, when all my chronic illnesses seem to flare simultaneously, orchestrating a cacophony of discomfort, I ask myself that question and wonder if others in my life are silently asking it too.

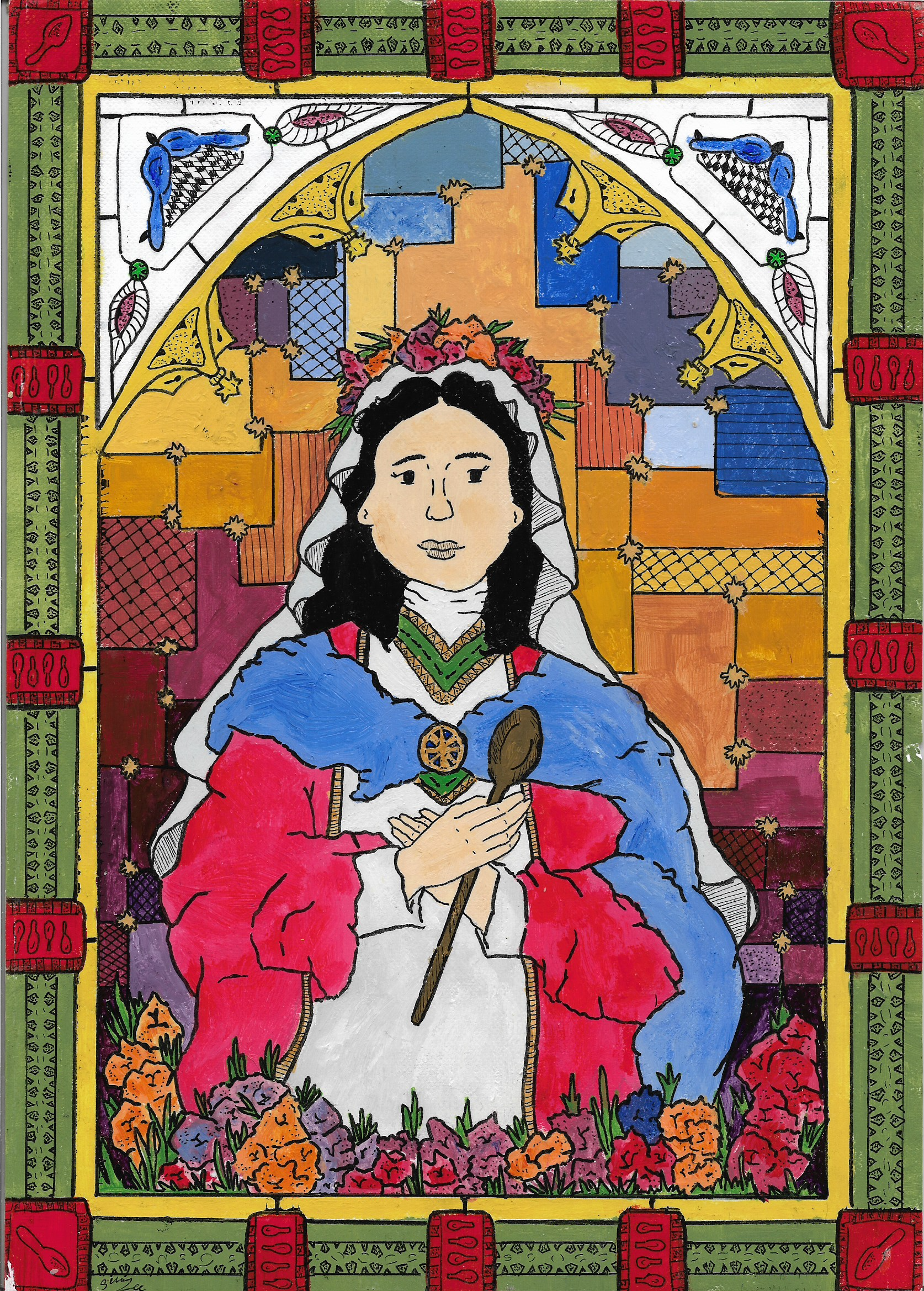

At the age of 24, I have been diagnosed with three chronic illnesses. Sometimes I feel like I am collecting them like Pokémon cards. I was first diagnosed at age 10 with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), specifically ulcerative colitis.

I remember throughout my adolescence and teenage years periodically filling out a symptoms questionnaire that asked about joint pain, rashes, and fevers. I was aware of the potential extraintestinal manifestations of IBD, but I was so focused on my gastrointestinal symptoms that I relegated any other discomfort to the sidelines.

At the time, I attributed those extraintestinal manifestations only to Crohn’s disease, so I avoided asking the doctor about my sleep attacks or leg pain. On a deeper, subconscious level, I avoided acknowledging the potential correlation between these other symptoms and my IBD because I would have had to accept the fact that my ulcerative colitis was not under control and was affecting more than my gastrointestinal (GI) system.

I was trying my best to maintain the cognitive dissonance of living with tangible symptoms, fatigue, and depression from my ulcerative colitis without fully acknowledging the ramifications of the disease activity on my whole body and overall health. I succeeded at ignoring the flares of my leg pain and increased sleep attacks that seemed to occur in concert with my colitis flares.

That’s part of the reason it took me almost 7 years to get diagnosed with sacroiliitis after I first began experiencing lower back and leg pain that left me with intermittent problems with mobility due to leg spasms and shooting pain down both of my legs.

No one could explain why I was experiencing such debilitating pain in my lower back and legs at such a young age: not my gastroenterologist, an orthopedic specialist, a physical therapist, a chiropractor, or, initially, a rheumatologist. It took me first researching chronic lower back and leg pain conditions that are comorbid with ulcerative colitis and then presenting the possibility of sacroiliitis to my rheumatologist for me to finally get diagnosed.

Once the MRI confirmed it, my rheumatologist noted my prowess in correctly diagnosing my own condition. I couldn’t help but think how silly it was that if I did not have the medical literacy and access to health information that I have due to my education and professional experience, I may have not gotten a diagnosis and treatment for my pain and mobility issues for who knows how many more years.

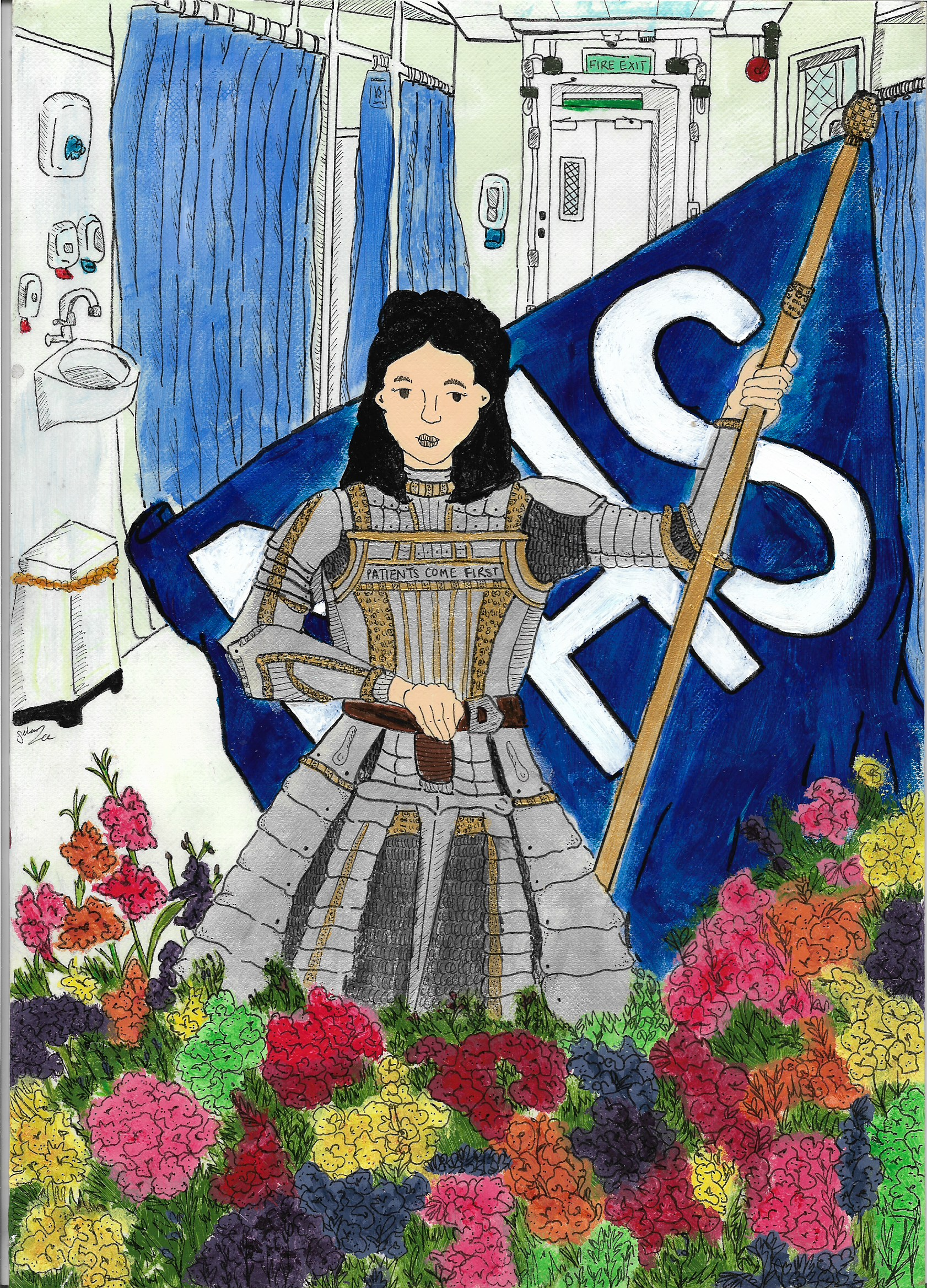

My next diagnosis of idiopathic hypersomnia at 23 after chronic sleep attacks also resulted from self-advocacy with my providers. When you are continually the one bringing medical attention to your disorders, it can be difficult to not have a type of medical imposter syndrome, essentially believing that you’re just a convincing hypochondriac. Having experienced a long diagnostic journey several times, it has become clear to me that it is not sustainable for chronically ill young adult patients to continually self-advocate for their health without their providers’ support. It is hard enough to live with a chronic illness like IBD as a young adult without having to feel like you are fighting for the care you need all on your own.

Providers who fully collaborate with patients on approaches to their care help to ease the burden of self-advocacy for chronically ill patients. They can partner with patients to think critically and innovatively about management and treatment options that align best with patients’ values, goals, and unique clinical histories. This partnership can lead to the proactive identification of connections between patients’ IBD and other aspects of their health and functioning (i.e., sleep, mental health, pain, fatigue) which can prevent gaps in care due to unaddressed needs or undiagnosed comorbid conditions.

It is no secret to many providers that IBD as an autoimmune disorder can affect more than the GI system and can be connected with other autoimmune or inflammatory disease diagnoses. This knowledge should be widely shared with patients, especially youth and young adults, to empower them to discuss their overall health in a holistic context. The focus should not solely be on the gastrointestinal system; fatigue, sleep issues, joint pain, mental health concerns, and various comorbidities are also relevant to IBD and should be addressed in tandem with GI care.

Provider and patient relationships should serve to empower patients to let providers know when they feel they’ve missed something. Providers should especially take chronically ill patients seriously when they mention newer pain or discomfort. As chronically ill youth and young adults, we spend a lot of our time getting to know our bodies as frequent flier patients. We know our bodies best and deserve to be taken seriously by our care teams.

It probably goes without saying that I shouldn’t have had to wait 7 years for a diagnosis and treatment of a chronic condition that, when active, makes it difficult for me to walk. Dismissing the pain of chronically ill patients because they tend to constantly experience pain or discomfort of some sort is an all-too-common occurrence. It is easy for providers to chalk the pain up to an already diagnosed disorder without probing it further. I can’t help but think, though, what the possibilities for improved quality of life and well-being could be if providers and care staff not only heard but listened to my voice.

Your pain should not be invalidated because you already have a lot of it. If you feel your providers are missing something, speak up. You are the real expert on your body and your health.

References:

Sacroiliitis: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment Options (clevelandclinic.org)

Idiopathic Hypersomnia (Mayo Clinic)

Featured photo by Medhat Ayad from Pexels.