NEWS

IBD, Mental Health, and Diet

Have you ever had a gut feeling before? Maybe you’ve had butterflies in your stomach when taking a risk, or felt something in the pit of your stomach when receiving bad news. Are these just idioms, or is there something else there? On my journey to become a registered dietitian, the connection between food and physical health is a common theme. Something we talk about much less is the connection between food and mental health. While Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is often thought of as a physical disease, the mental impact cannot be ignored. In my opinion, we don’t talk enough about the IBD and mental health connection, and we certainly don’t talk enough about how food can play a role in this aspect of our disease.

Mental Health and Gut Health

What does gut health have to do with mental health? Strap on your helmet, it's time for a crash course in the connection between gut health and the brain. The gut has over 500 million nerves, which serve as a two way communication system with the brain. If your gut isn’t happy, you better believe it is going to let its good friend the brain know about it. Our guts are also responsible for producing neurotransmitters, which help to regulate physical and mental functions of the body. One important neurotransmitter that regulates mood, serotonin, is produced 95% in the intestines! Another one, GABA, can be produced by the friendly bacteria in the gut, and can help reduce feelings of anxiety, depression, and fear.

Mental Health and IBD

As you can see, the gut and the brain are basically best buds. But what does that mean for people whose guts are broken more frequently than the McDonalds ice cream machine? Unfortunately, IBD patients are at an increased risk for developing anxiety and depression, and frankly, can you blame us? We are forced to bear the burden of a lifelong chronic disease, often being diagnosed during some of the most mentally vulnerable stages of our lives. High school is hard enough without explaining why you spend half of every class in the bathroom. It might seem like the connection between intestinal health and brain health is bad news, but there is a silver lining. If we can change the health of our gut, we can change the health of our brain.

Diet and Mental Health in Healthy Individuals

In healthy individuals, certain diets have been shown to increase feelings of wellbeing, reduce feelings of depression, and improve psychological health. Both individual foods such as fruits and vegetables, as well as dietary patterns such as the mediterranean diet, have been linked to these benefits. Some foods are also associated with worse mental health. Sugar has been linked with mood disorders and depression. Excess sugar consumption is also associated with dysbiosis, a shift in the composition of the gut bacteria from helpful to harmful species.

Diet and Mental Health in IBD

In a study presented at Digestive Disease Week 2020, researchers categorized IBD patients into two groups, a high sugar group (>100 grams per day) and a low sugar group (<100 grams per day). They found that those in the high sugar group had increased feelings of fatigue, trouble with social engagement, feelings of depression, and trouble relaxing compared to IBD patients in the low sugar group.

It is important to note that sugar containing whole foods such as fruit have been strongly linked to positive health outcomes, and should be considered differently than sugars from processed foods. Added sugars from processed foods such as soda or candy are associated with an unhealthy gut, and worse overall health.

I think this is such an important study, not only because it has practical implications for IBD patients, but also because it opens doors for patients to take control of their own mental health. I don’t think I've ever had a conversation with any GI doctor about mental health, despite the increased risk we carry with IBD. Until that changes, it is reassuring to know that we have the option to eat in a way that is associated with good gut health, and therefore good mental health.

References

Choi K, Chun J, Han K, et al. Risk of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide, Population-Based Study. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5):654. Published 2019 May 10. doi:10.3390/jcm8050654

Knüppel, A., Shipley, M.J., Llewellyn, C.H. et al. Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: prospective findings from the Whitehall II study. Sci Rep 7, 6287 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05649-7

Stranges S, Samaraweera PC, Taggart F, Kandala NB, Stewart-Brown S. Major health-related behaviours and mental well-being in the general population: the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e005878. Published 2014 Sep 19. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005878

Parletta N, Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci. 2019;22(7):474-487. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320

Brown K, DeCoffe D, Molcan E, Gibson DL. Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease [published correction appears in Nutrients. 2012 Oct;4(11)1552-3]. Nutrients. 2012;4(8):1095-1119. doi:10.3390/nu4081095

What I Wish My Newly-Diagnosed Self Knew

Sitting in the patient chair, hearing your doctor say “you have Inflammatory Bowel Disease” can be terrifying and change your life in a matter of seconds. These words come with both a massive feeling of relief and validation, knowing that your symptoms are not just in your head and that you will finally receive the help you deserve. But, along with this relief, comes terrifying thoughts, too many google searches, and the realization that you will have this diagnosis for the rest of your life. Feelings such as anxiety, fear, and loneliness follow with no sense of direction. When looking back at my newly diagnosed self, I wish I could hug her and tell her everything I know now.

It‘s not your fault

The guilt that comes with a new diagnosis is unexplainable. My mind wandered, time and time again, over what I might have done to cause my diagnosis. Was it loving toaster strudels as a kid and eating a few too many? Was I too stressed at my internship? Was it previous medications that disrupted the microbiome in my gut? The truth is, you can let your mind wander for as long as it wants, but you are NOT the reason behind your illness and you are NOT at fault. Many people, including myself, strongly believe and are determined that everything has a purpose and that everything happens for a reason. Although some may argue this belief, obsessing over what may have caused your diagnosis and blaming yourself will do nothing but harm. Inflammatory bowel disease is not the result of a bad decision or bad karma, and something that is most important to understand is that you are not to blame. Once you come to peace with your diagnosis and become confident in the unknown, you will begin to heal in ways you never have before.

The importance of your healthcare team

As a young adult diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, I was scared, lonely and afraid. After years of fighting for a doctor to take me seriously, I felt unworthy of receiving proper treatment and advocating for myself to my healthcare team. With help from a handful of individuals, I slowly realized that I should be looked after by healthcare professionals that listen, support, and are trustworthy. Not only does this apply to gastroenterologists, but also to other medical professionals that make up your healthcare team. If your gastroenterologist does not support you and undermines your symptoms, shop around for a new gastroenterologist that makes you feel comfortable, heard and safe. Additionally, a gastroenterologist is not the only medical professional that should be on your team. If you are able, reach out to a dietician, nutritionist, or naturopath certified in food nutrition to receive guidance on diet, food choices, vitamins, and supplements to support your health. Lastly, do not be afraid to seek out help for your mental health. The stress that comes with a new diagnosis can be extremely heavy, and for some, stress can aggravate GI symptoms and flares. The best decision I made was seeing a therapist to help me through my past traumas and transition into entering society post-diagnosis while dealing with debilitating symptoms. A wide range of healthcare professionals will allow you to thrive and succeed in ways you didn't even know were possible. Here in Canada, dieticians, nutritionists, naturopaths, and therapists are not covered by OHIP. If you do have insurance, these types of professionals are usually covered. If you are not able to cover the costs for these additional healthcare professionals, reach out to your GI to see if there are any subsidized or low-cost options available to you. Also, many universities and colleges offer free or low-cost therapists and nutrition counselling.

Find your support group

An Inflammatory Bowel Disease diagnosis is scary and may leave you feeling as if you need to be independent through this journey as you don’t want to burden others. Putting up a wall and pretending like you are fine is something I did more times than I should have after my diagnosis. I had such a hard time being vulnerable and admitting I was not ok. With that being said, the best thing I could have done was confide in a few trusted friends and family members. Opening up to my loved ones allowed me to feel more comfortable asking for help when it was needed and having a safe space to vent. Opening up to my support system allowed me to express my fears and challenges, gave me the opportunity to have someone join me at healthcare appointments and to also receive help when I was flaring.

If you are located in Canada, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada not only offers regional support groups where you can meet fellow peers with IBD, but they also offer a mentorship program where you have the opportunity to be mentored by someone who is experienced in navigating the hardships of IBD. Additionally, reach out to your schools accessibility centre to find out if there are any IBD groups with individuals around your age to network with. Lastly, joining Facebook or Instagram pages that connect others with IBD is a great way to speak to people who understand what you are going through.

Grief

As a newly diagnosed young adult, the negative feelings and thoughts of living with a chronic disease for the rest of your life can be endless. Dealing with healthcare appointments and debilitating symptoms that not many other young adults experience can leave you feeling defeated and hopeless. Something important that I have learned throughout my journey is that it’s important to sit in those feelings and take the time you need to process them. Take time to grieve your old life and the life you pictured for yourself, but also remember everything positive that this diagnosis will give you. You will be stronger, resilient, and more empathetic to those around you. You will view the world in such a way that you never have before, and you will become more intuitive with your body and mind through this journey. If your feelings of grief become overwhelming, reach out to a trusted friend, family member or a mental health professional. Although my diagnosis has been challenging to say the least, I promise you there are things my diagnosis has given me that I am beyond grateful for and I wish I was reassured of when I was newly diagnosed.

To the newly diagnosed IBD warriors, you are amazing, resilient and strong. An unpredictable and serious diagnosis such as IBD will be challenging and difficult, but you are not alone and you never will be.

The Patient-Doctor Relationship

Why is a good relationship with the doctor important for patients?

Have you ever considered how your relationship with you doctor affects your health?

“There is no cure. Only control of the disease symptoms”. How many times have you heard this? How harsh does it sound, especially the first time?

Are you ready to build a new relationship, a completely different relationship with your doctor? This relationship will be unlike any other relationship and certainly no one has experienced it again until the time of diagnosis.

This is a long-term relationship that will evolve over time. Your doctor will know many things about your personal life, your job, your family, etc. Above all, however, over time, he or she will learn YOU, and your personality.

And why this is important?

As a patient you have to break down the wall around you and allow the doctor to enter your world, the world of your disease and how you experience it, even for a while. Of course, the doctor must have the empathy required for that.

This will not happen overnight. It may take years to build this relationship. As this relationship begins to build, you will feel the doctor as a member of your family, you will share with him or her important moments.

Is always the relationship between patient and doctor like that?

Unfortunately, no - however, I deeply appreciate those doctors who patiently and carefully support patients with chronic diseases. It’s nice to see a person being 100% present.

Journaling with IBD: A Focus on Mental Health

During 2020’s intermittent quarantine, what has brought me more solace than anything is the act of journaling. As someone who was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease during the pandemic, much of my hospital experience was drastically different than others. Increasingly isolated from my loved ones, I could feel the weight of my diagnosis crushing me, the four walls of my hospital single closing in.

For IBD patients specifically, mental health is tied so closely to our physical health. I’ve had days where my physical flare-ups make me double over; it’s no coincidence that those same days, my mood swings and sensitivity levels are out of control. In fact, this phenomenon is so common that there’s an actual term for it: the gut-brain connection.

The gut-brain connection refers to how changes in our gut can have drastic impacts on how we feel and behave. Many tend to dichotomize our bodily systems, finding it hard to believe that our behaviors and moods can be swayed by what we eat and how our gut reacts. This is explained by what’s called ‘bi-directional’ communication, in which our gut and brain talk to each other using different pathways.

Re-focusing energy is powerful. With enough time, journaling can become a way to channel your energies into finding peace and introspection. What’s best about all this is that journaling can take any form you want it to. It’s simply a way to get your thoughts out on the page. Humans absorb so much information and stimuli during their waking hours; life, as it turns out, can be overwhelming at any point in time, regardless of an IBD diagnosis or not.

Journaling should be a way to relieve stress, a way to declutter your mind. I’ve found it especially helpful to process my physical and mental pain; even doodling can help distract your mind for a few minutes. Especially for patients with IBD, a journal can be a place to record symptoms, reflect on treatments, or even track what foods you’re eating (Check out this article on how to start a food diary by David, a 2021 CCYAN Fellow!)

All you need is a notebook, even just a piece of paper, and a pen or pencil. Some people find it helpful to pair a journaling session with a few minutes of meditation: this is your choice! Whatever makes you feel the most grounded and relaxed.

Here are a few journaling prompts to get you started:

How are you feeling right now?

What does your body need?

What is giving you energy? What is taking your energy?

What are you grateful for, at this moment?

What are some themes in your life right now? (rest, peace, healing, etc.)

Things that feel heavy today; things you can try and release today.

What do you need to let go of in order to move forward and grow?

What beliefs and assumptions are holding you back?

What do you have to be proud of?

Where are you feeling stuck? Where are you feeling growth?

Celebrating Black History Month in the IBD Community

“Representation creates trust, so why aren’t there more people who look like me included in research and education?” This quote by Melodie Narain-Blackwell brilliantly describes the feelings that so many Black and brown IBD patients have. In recognition of Black History Month, what can we as a chronic illness community do to support our fellow Black IBD patients this month? Standing in solidarity with this marginalized community, helping amplify their voices, and acknowledging their experiences are ways to starting bridging those gaps.

It is important to support BIPOC patients by recognizing the additional barriers that minorities, especially those in the Black community, face when navigating medical care and public health. Historically, Black people have been marginalized, abused, experimented on, and underrepresented in medical trials and research. Being seen as easily disposable, Black people have had to endure the systemic injustices of medical discrimination and medical racism. Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis are chronic diseases that statistically occur less frequently in African-Amercian populations. Statistics also show that Black people are more likely to not have their symptoms believed or validated, which has ushered a crisis of misdiagnoses. It is clear that implicit bias and antiquated medical beliefs are factors in the hesitation that Black people experience in the medical field. This phenomenon has led to an inherent distrust of medical institutions and treatment in the black community. As IBD patients we understand that having the right diagnosis and starting treatment is vital for healing and longevity. This concern is magnified in the Black community due to the systemic injustices previously mentioned.

When I first started to become ill in 2019, I did have some internal generational trauma that made me hesitant when seeking medical care. After months and months of pain I finally decided to go to the hospital to get some answers. When speaking to the doctor about symptoms, I vividly remember feeling an overwhelming sense of unease rattle through my bones. What happens if my experiences and symptoms aren't taken seriously? How can I truly convey the severity of how I feel? Although I did not receive a proper diagnosis from the hospital, I was lucky enough to have the staff members at the hospital believe and validate me. I was privileged that this was not an overtly terrible experience, but it does not take away from any reservations I had, as well as the reservations that countless other Black people have.

We must acknowledge and hold space for Black people within the IBD community through advocacy. Having a diverse range of anecdotes and stories will only propel this community to further embrace the lived experiences of so many Black and brown people who are voiceless. Education and conscious activism will only lead to more positive intersectional change.

In recognition and celebration of Black History Month, here are a few black pioneers in the IBD community as well as Gastroenterology:

Sadye Beatryce Curry was the first female African-American gastroenterologist in the United States. On top of her endless list of accomplishments, she was a founding member of the Leonidas Berry Society for Digestive Disease as well as the first woman to be elected chair for the Internal Medicine Section of the National Medical Association.

Leonidas Berry was the first African-American gastroenterologist in the United States as well as a pioneer for the advancement of endoscopy procedures. Dr. Berry also invented the gastroscopy scope. Leonidas Berry has a passion for bridging the gap of racial problems in public health.

Gary Richter is a gastroenterologist and currently runs Consultative Gastroenterology in Atlanta, and has become the first African-American president of the Medical Association of Atlanta.

Melodie Narain-Blackwell is the founder of Color of Crohn’s and Chronic Illness (COCCI) which is a nonprofit focused on increasing quality of life for minorities who battle IBD and related chronic illnesses.

Pandemic, Lockdown, Isolation and Chronic Illness

It has been almost a year now and we are still in the middle of a pandemic waiting for our lives to return to normal. However, reality may never be the same again.

So much has changed, but it seems like nothing and it makes it difficult to feel the comfort of real security.

My return - and the return of many other patients with chronic conditions- to normality may be further away than most of you. But I know that all this is equally difficult for all of us.

They say that only the elderly and people with underlying diseases are at risk. The vulnerable population.

But what happens when you are the vulnerable?

I belong to those who they call vulnerable. I never hid my illness nor was I afraid of the stigma.

I look young and healthy, but I’m not!

I’m immunosuppressed, which makes me vulnerable to any kind of infection.

We have been in lockdown for months. This is certainly not easy, nor is isolation.

I understand that it is difficult to change your daily life, but do you know how many times we, the vulnerable, have changed our daily lives not because we wanted to, but because our health imposed it?

How many times have we canceled a plan at the last minute, favorite foods we stopped eating, parties we missed and much more?

For those of us who are vulnerable, it is not so foreign to stay home, since we have spent long stays in our home and before COVID-19.

I am in quarantine for a long time. It is not easy, it dissolves your mood, your body. Staying home is unbearable for everyone.

Isolation, despair.

And it is now that we are all looking for ways to balance our security with our contact with the world.

All of this is not so foreign to me. I have some chronic illnesses that require me every day to choose what to do and what not to do. Even before the pandemic, I was very careful, evaluating what was safe to do and what was not.

I do not understand big differences in my own life now with quarantine; that I am not allowed to be touched, that I can not go to the hospital and maybe two or three more things.

And recently I made a finding that has a lot in common with today's reality.

I realized that my illnesses will never leave me, while a cure seems like a distant dream for now.

Yes, I can take steps to improve every day, but what I thought as “normal” in previous years may never come again. For many years I waited for the cure to continue my life. Now that I accepted that I would carry my diseases with me, I gained freedom. My goal now is not to be cured, but to live better.

So as I realized that it is not realistic to wait for the cure to live, so is the pause we have entered because of COVID-19 until our life is “normal” again.

And this is the real challenge: how to move on and stop waiting to get back to normal.

Stay safe!

Challenges as a Crohn's Warrior in Malaysia

In Malaysia, Crohn’s disease is also known as “Western Disease” or “Rich People Disease.” The reason behind this is mainly because Crohn’s is a rare disease in Asia, particularly in Malaysia, as compared to Western countries. Many in Malaysia have never heard of this disease. Therefore, they are not aware of the Crohn’s and colitis patients’ struggles with their pain, medical procedures and psychological issues.

At the beginning stage, I had no one to guide me. I had no idea on how to handle my newly diagnosed disease. With no medical background, no one in the family or friends with similar conditions, I struggled to cope with this disease and my normal life. Can you imagine the struggles I faced as a first year university student with my condition? I was alone and I didn’t even understand what was going on and my normal was no longer a normal. The internet was my only resource for information other than my doctor. By reading everything I could find in the internet, I slowly started to understand this disease. Back then, there wasn’t even a support group for Crohn’s in Malaysia as the disease is relatively unknown to Malaysians. In fact, I didn’t even known about any other Crohn’s patients until I met one almost a year later after my diagnosis. My gastro doctors encouraged me and other patients to start a group so we could create a support system to each other. Now, newly diagnosed Crohn’s patients or caregivers in Malaysia have access to few channels that they could use to discuss, ask, guide and support each other going through this painful disease.

Living with chronic disease, I had to adjust and adopt to new diet and lifestyle. Changes in diet were mostly trial and error in the beginning. I had to monitor my consumption and take note of any changes. Why did I have to monitor those changes? It is simply because I wanted to avoid flare ups that were caused by certain food that I consume. For me, I found that my Crohn’s is mostly under control when I avoid foods that contain eggs. So I have to ensure my daily food consumption is egg free. If I didn’t, I’d have to visit toilet frequently the whole day. Precaution is needed for Crohn’s patients because flare ups can happen in any situations, therefore any heads up is a good one to have.

Apart from my diet, I had made some massive changes to my daily activities too. Since I’m an Ostomate, I have to ensure that I don’t partake often in hardcore sports in order to avoid stoma prolapse.

The understanding and acceptance of IBD in society is still a challenge for me. Most of them, as I mentioned above, do not know about Crohn’s disease. I remember one of my friends asking me “Sara, is your disease infectious?”. At that time, I just laughed and say “No, it doesn’t”. The lack of awareness, although understandable, is a huge disappointment when someone I confided in is not taking any initiative to understand it.

Stress is another thing that I started to consciously manage. What is the connection between Crohn’s and stress? Well, stress generally affects a person emotionally and mentally as it damages a person’s emotional equilibrium. But it also affects the person’s health. Even a person without chronic disease can feel their health being affected by high stress levels. So, anyone with chronic health issues, such as IBD patients, have higher chances of having a relapse and flare when they are stressed. It is imperative that I recognize my stress inducers, my stress level, my tolerance level and ways to reduce stress so that I do not have chronic flare ups. Although it is impossible to live stress free all the time, I believe that I should try to manage stressful situations to the best of my abilities.

Navigating relationship with Crohn’s is complicated and challenging. Crohn’s has created ups and downs in my relationships with my family, friends and loved ones. In the beginning it was really hard to explain to them my condition. They did not understand the condition or why and how I got this disease in the first place at all. It took a while for my family to accept my condition and now they are slowly getting used to it. They are a great support for me at the moment, and my heartfelt thanks.

Dealing with Crohn’s is tough enough and unfortunately, Crohn’s is not something that we can ignore or that it will disappear one day. Every single day is a challenge for me because I go through physical and psychological pain. I have to survive, improve my quality of life and live my life as normal as possible; I hope more people will become aware of Crohn’s disease, of patients’ struggles, and accept their conditions. Be kind even if you don’t see someone’s struggle, their pain or their decreasing health.

How to Start a Food Diary

Dear Diary,

Sometimes when I eat it feels like a herd of angry buffalo have taken up residence in my gut. The rumbling, the pain, and the regret are all too familiar at this point. Maybe I just shouldn’t eat at all. Maybe that would be best. I wish it could just stop…

Okay, I might not be talking about that type of diary, but I’ve had many days in my Crohn’s journey where that could have described me. Like many people with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), I have a frustrating mix of good days and bad days. It always baffled me how I could feel good one day, but terrible the next. I wanted to know why. This started my journey of paying closer attention to what I eat, and in turn, keeping a food diary.

Why a food diary?

Our environment is everything we come in contact with on a daily basis that isn’t us. The air we breath, the things we touch, and the food we eat all make up our outside environment. If nothing in our environment impacts a disease, it should feel the same every single day. For me, and many others with IBD, this just isn’t true. In this case, we must start looking at our environment as a source of triggers for our disease.

One of the largest parts about how we interact with our outside environment is what we eat. Every day we eat a variety of different foods, from a variety of different places, that have a variety of different health effects. For me, food was an easy place to start to try to figure out some of my disease triggers. I know what I am eating every day, so why not try to see if there is any connection between what I eat, and how I feel. This led me to food journaling, and it has been an invaluable resource in helping me navigate and manage my own disease. It has given me power.

Research also backs up this idea. In one study done in 2016, one group of Crohn's patients was told to exclude either the four food types they had the highest antibodies to, while the other excluded the four food types they had the lowest antibody to. The group that excluded the foods types to which they had the highest antibodies had significantly lower disease activity and significantly higher quality of life.1 We might not have access to antibody testing, but we can certainly try to figure out what foods are worsening our disease and quality of life.

How to write a food journal

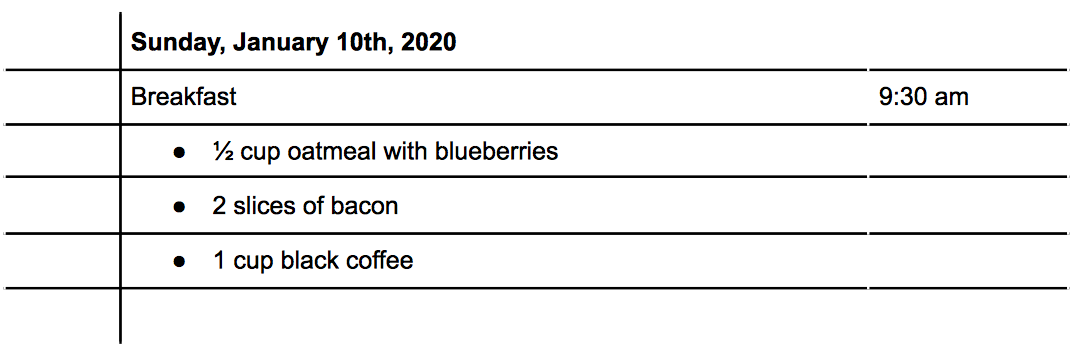

There are three main things to consider when writing a food journal: what you eat, the time you eat, and how much you eat. With these three written down, you will be able to better make connections between foods and symptoms. Let's do an example: For breakfast this morning, you ate a bowl of oatmeal with blueberries, some bacon, and a cup of coffee (I know, I know, coffee isn’t exactly known for its stellar track record in collaborating well with IBD, but it's a made up example!) How would that look?

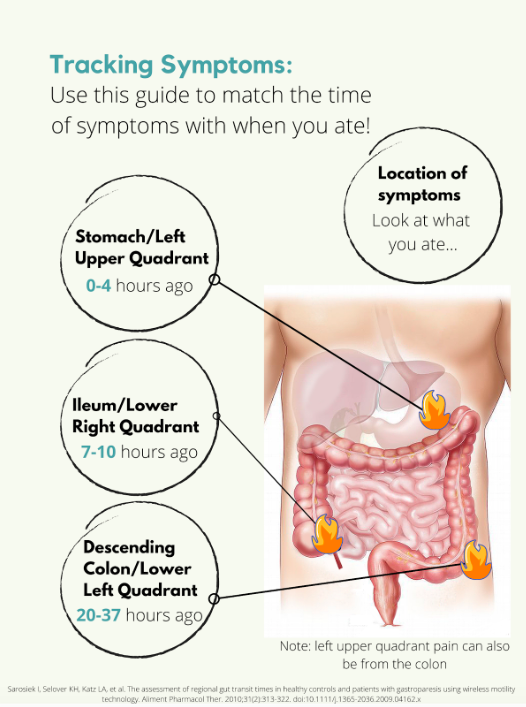

Tracking Symptoms

Symptoms are a little trickier. Say you have some pain in your lower right abdomen, how do you know what meal might have triggered you? Was it the meal you ate 5 minutes ago? 4 hours ago? The day before? For this we need to know a little bit about how long food takes to get to each different part of the intestines, also called the intestinal transit time. In a normal, healthy adult the following is accurate:

But what if you’re flaring? Diarrhea, inflammation, stricturing, and other aspects of a flare can all impact the amount of time it takes for food to get to the finish line. Some studies have been done on intestinal transit time in IBD patients, with most finding that the intestinal transit time is longer in IBD than in normal healthy subjects.2,3,4 In one patient with Crohn's disease, it took 156.2 hours for one meal to pass through. Talk about taking the scenic route! Like many other things with IBD, you are going to have to take an individual approach and problem solve to figure out how to best match symptoms and meals.

Resources

Tracking food can be done in something as simple as a spiral notebook, but there are also other options available. Here is a list of some apps you could use instead of a physical journal:

mySymptoms Food Diary & Symptom Tracker (Lite) by SkyGazer Labs LTD

Food Diary by WeCode Team

Cara Care by HiDoc Technologies

References

Gunasekeera V, Mendall MA, Chan D, Kumar D. Treatment of Crohn’s Disease with an IgG4-Guided Exclusion Diet: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2016/04/01 2016;61(4):1148-1157.

Andersen K, Haase A, Agnholt J, et al. P-113 Gastrointestinal Transit Times and Abdominal Pain in Crohn's Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2017;23(suppl_1):S40-S41.

Fischer M, Siva S, Wo JM, Fadda HM. Assessment of Small Intestinal Transit Times in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease Patients with Different Disease Activity Using Video Capsule Endoscopy. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18(2):404-409. doi:10.1208/s12249-016-0521-3

Haase AM, Gregersen T, Christensen LA, et al. Regional gastrointestinal transit times in severe ulcerative colitis. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2016;28(2):217-224.

Advocating for the Specialized Care You Need: Reflections on Mount Sinai’s IBD Clinic

Recently, I’ve started receiving care from the Susan and Leonard Feinstein Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Center at Mount Sinai. This was my first time visiting an IBD-specific clinic, ever. Prior to visiting Mount Sinai, I was lucky if there was a gastroenterologist or a colorectal specialist on call at my local hospital.

On my most recent visit to the IBD Clinic for a post-operation appointment, I thought I’d reflect on what made this center so special, especially during the COVID-19 era.

Post-surgery for an internal fistula -- feeling better already!

In light of the pandemic, the process for being admitted and seen (at any hospital!) has been streamlined into a tighter and safer protocol. With hand sanitizer stops at nearly every corner, I noticed that Mount Sinai took a heightened level of precaution than any other facility I had been in. Every doctor, nurse, and staff member had a face shield in addition to their masks, with some going as far as to don Bouffant caps.

Beyond the COVID-19 precautions, however, I would like to speak to the deeper and more important differences at this clinic -- the unspoken sense of solidarity between both patients and doctors alike. To have an entire facility devoted to this condition, a chronic illness shared by millions of Americans nationwide, means that there is a lack of cause to explain yourself. Everyone in the room is deeply familiar with the forms of IBD, along with all the embarrassing and critical details that few others are willing to talk about in their entirety.

The waiting room at the Mount Sinai IBD Center is all socially distanced!

This plaque, hung on the entryway of the floorwide clinic, is perhaps one of my favorite parts of the IBD Center. It’s a reminder of how fortunate we are, as young adults with IBD, to be treated in a time where our condition has been identified and researched, nevertheless with a name and prognosis. It is a strange feeling, indeed, to know that the work and medical achievements of this doctor (and his name!) has forever changed my life.

A plaque memorializing Dr. Burrill Crohn at the Mount Sinai IBD Center.

Of course, I would be remiss not to acknowledge how incredibly fortunate I am to live in the vicinity of this clinic. To have access to such a clinic with a focus on IBD in and of itself is a privilege, one that many Americans and patients are not so lucky to receive. I’m duly compelled, however, to point out how lacking our healthcare system is, especially for those suffering with chronic illnesses. As someone who was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in the summer of 2020, a time when the SARS-CoV-2 virus revealed the greatest inequities and vast underpreparedness of American healthcare, I’ve come to meet, learn about, and further appreciate the frontline and essential workers, who are simply making the most of what they’ve got.

Although it took me months to find the right team of doctors and healthcare professionals, I learned that it was alright, and at times, even necessary, for me to ask for more specialized degrees of care. An important lesson in my brief yet transformative journey with IBD: don’t be afraid to advocate for the specialized care that you need.

Reflections: The Importance of Advocacy for IBD

It’s a little strange to title this article ‘Reflections,’ because IBD is unique in that it’s always ongoing, with nothing to really jump over and look back on to reflect; with the journey still very much running, our reflections are inbuilt into it.

As I write this, I’ve been in remission from ulcerative colitis for more than a year. From the time I was accepted to be a CCYAN fellow to now, I have already been through a rollercoaster of new emotions: from immense gratitude and relief that I am finally a fellow of a network that I closely followed for several months to staggering self-doubt about whether I can truly do this opportunity justice. While poles apart, my feelings of gratitude and self-doubt and the largeness of the two do stem from the same root. After I was diagnosed with UC at the age of 19, I desperately needed to know more people who faced the same struggles. With little else to focus on in those starting years, hope would glimmer every time I found out about a famous personality or someone I knew who opened up about their chronic illnesses.

The way an invisible chronic illness creeps up on young adults is very much like a thief breaking in your house when you’re asleep and stealing things that don’t seem so valuable at first sight but without which you can’t really survive (like all your dishes). As young adults, we are so entitled toward our bodies and organs functioning properly that there’s no way to prepare or even know you will be impacted and when you do, people have very strong opinions on what you could have done to avoid it. And if, like some organs, dishes weren’t replaceable and the upkeep of the damages was constant, the last thing anyone would want is to deal with the struggle alone and keep it private. At least that’s how I felt. As soon as I was diagnosed, I let everyone around me know mostly everything except for the “impolite” specifics. Sometimes if the gravity of my situation wasn’t acknowledged, I would push to reveal the impolite specifics too. Concurrent to my health challenges, I was still also learning aspects of a broad society I had entered just two years before I got UC. As I rushed to speak and be heard, I realized, through the fear of my family and the discomfort of peers and friends, just how closed this society is towards these things.

When there are no voices for something that drastically alters every aspect of your life, it feels as though you’ve been dropped off to a completely new city with no maps for guidance. Maps are important for not only getting you from point A to point B, but also giving you a sense of orientation to gauge where you are with respect to everything around you. No voices = no maps. By far, in India today, invisible illnesses not only lack visibility in patients' external bodies, but also in national and private datasets, policies, and advocacy. This leaves patients disorientated and vulnerable to quackery (health fraud), which results in the loss of crucial time, finances, and deterioration of mental health (with the ups and downs of new hope and disappointment).

If the silence around personal disturbances was anything to go by, then I did not do a very good job of fitting in to my society as I always took the opportunity to talk about what I was going through even when I realized with passing time that it wasn’t always welcome or understood completely. I thought I should speak up all the more, because if no one does, who will vouch for me? This casual monologue took greater form in my first experience of being at a public hospital in my city. By that time, I had scoured the internet for people like me, experiences like mine, unique symptoms like mine, etc. I had come to recognize some feelings that came as a by-product of my illness through Hank Green’s videos on YouTube, and that the illness was bigger than me and my doctors (who only focused on the strict textbook aspects of IBD). My mom and brother very supportively drove and accompanied me for my sigmoidoscopy and I even got to sit as I waited for my turn. Waiting for countless hours after the scheduled time of my appointment, I was busy drowning in my pond of self-pity. When I heard a young lady slightly older than me was invited to go before me, I was very irritated and urged my mom to leave and reschedule. My experienced mother knew better. As I waited, I could hear the conversation between the young patient and the doctors in the room next door. She was a daily wage worker and her grumbles about missing work, her stomach pain (due to which she tilted sideways when she walked) and the tedious hours she spent waiting for her turn followed her into the room. The doctors didn’t indulge her in any sympathy, but rather curtly started the process. I wondered out loud why they hadn’t offered her a sedative – whenever I was asked, I always thought what a preposterous thing to ask when the process was so intrusive and uncomfortable. It was because she was alone and needed to hear the doctor’s findings and, of course, had to head back home alone. Even in my miserable state, that struck something in me. Her yells and shouts during the process, and the surrounding patients’ aloofness painted a picture so bleak, I was forced to look beyond my situation and recognize that despair like mine was still placed high on privilege. Granted that sigmoidoscopies are not the most pleasant of processes to go through or even prepare for, her shouts seemed out of place. I gathered it was more of a release from the anxiety of being alone and in such a vulnerable position with no emotional support. It took me back to a brief, mostly one-sided exchange she and I had before she was called in. From the little I understood as she spoke rapidly in her dialect, she had absolutely no understanding of the formalities of the prep that had to be taken and, more worryingly, the seriousness of her illness. She had two kids she had to care for, and she came alone because her husband was a daily wage worker who could not miss work especially since she was missing work that day too. She complained to me about the high prices of prep, all the days she had missed getting tests done and scheduling and rescheduling appointments in a government hospital, her appetite loss due to nausea and how she couldn’t perform her labor-intensive work as efficiently. After she limped out of her session, I thought of the sheer population of people like her in India.

Ever since that episode, I started thinking beyond my illness and what I could do to help the numberless amount of people in the same boat as the young woman. To start helping, the first step is to get a clear picture of how many people are impacted by IBD, which is frustratingly not available nor acknowledged anywhere in India. I am grateful, therefore, that I found CCYAN as an international platform for advocacy. Advocacy would hopefully enable data collection somewhere down the line. However, sometimes the mountain looks too big to climb; at this moment, we are right at the bottom and there are many things to do. Sometimes I think of all the people suffering from IBD in India, and how many struggles go undiscovered due to health illiteracy, digital gaps, doctor unavailability, and expensive medication, etc. Now more than ever, as cases of autoimmune disease rise across the world, there needs to be a prominent force of advocacy for IBD in India, so that datasets can be recorded and informed policies can be formed. The innumerable people who struggle already for a living should not be further hindered in their struggle for support, information or resources in this regard.