NEWS

Challenges as a Crohn's Warrior in Malaysia

In Malaysia, Crohn’s disease is also known as “Western Disease” or “Rich People Disease.” The reason behind this is mainly because Crohn’s is a rare disease in Asia, particularly in Malaysia, as compared to Western countries. Many in Malaysia have never heard of this disease. Therefore, they are not aware of the Crohn’s and colitis patients’ struggles with their pain, medical procedures and psychological issues.

At the beginning stage, I had no one to guide me. I had no idea on how to handle my newly diagnosed disease. With no medical background, no one in the family or friends with similar conditions, I struggled to cope with this disease and my normal life. Can you imagine the struggles I faced as a first year university student with my condition? I was alone and I didn’t even understand what was going on and my normal was no longer a normal. The internet was my only resource for information other than my doctor. By reading everything I could find in the internet, I slowly started to understand this disease. Back then, there wasn’t even a support group for Crohn’s in Malaysia as the disease is relatively unknown to Malaysians. In fact, I didn’t even known about any other Crohn’s patients until I met one almost a year later after my diagnosis. My gastro doctors encouraged me and other patients to start a group so we could create a support system to each other. Now, newly diagnosed Crohn’s patients or caregivers in Malaysia have access to few channels that they could use to discuss, ask, guide and support each other going through this painful disease.

Living with chronic disease, I had to adjust and adopt to new diet and lifestyle. Changes in diet were mostly trial and error in the beginning. I had to monitor my consumption and take note of any changes. Why did I have to monitor those changes? It is simply because I wanted to avoid flare ups that were caused by certain food that I consume. For me, I found that my Crohn’s is mostly under control when I avoid foods that contain eggs. So I have to ensure my daily food consumption is egg free. If I didn’t, I’d have to visit toilet frequently the whole day. Precaution is needed for Crohn’s patients because flare ups can happen in any situations, therefore any heads up is a good one to have.

Apart from my diet, I had made some massive changes to my daily activities too. Since I’m an Ostomate, I have to ensure that I don’t partake often in hardcore sports in order to avoid stoma prolapse.

The understanding and acceptance of IBD in society is still a challenge for me. Most of them, as I mentioned above, do not know about Crohn’s disease. I remember one of my friends asking me “Sara, is your disease infectious?”. At that time, I just laughed and say “No, it doesn’t”. The lack of awareness, although understandable, is a huge disappointment when someone I confided in is not taking any initiative to understand it.

Stress is another thing that I started to consciously manage. What is the connection between Crohn’s and stress? Well, stress generally affects a person emotionally and mentally as it damages a person’s emotional equilibrium. But it also affects the person’s health. Even a person without chronic disease can feel their health being affected by high stress levels. So, anyone with chronic health issues, such as IBD patients, have higher chances of having a relapse and flare when they are stressed. It is imperative that I recognize my stress inducers, my stress level, my tolerance level and ways to reduce stress so that I do not have chronic flare ups. Although it is impossible to live stress free all the time, I believe that I should try to manage stressful situations to the best of my abilities.

Navigating relationship with Crohn’s is complicated and challenging. Crohn’s has created ups and downs in my relationships with my family, friends and loved ones. In the beginning it was really hard to explain to them my condition. They did not understand the condition or why and how I got this disease in the first place at all. It took a while for my family to accept my condition and now they are slowly getting used to it. They are a great support for me at the moment, and my heartfelt thanks.

Dealing with Crohn’s is tough enough and unfortunately, Crohn’s is not something that we can ignore or that it will disappear one day. Every single day is a challenge for me because I go through physical and psychological pain. I have to survive, improve my quality of life and live my life as normal as possible; I hope more people will become aware of Crohn’s disease, of patients’ struggles, and accept their conditions. Be kind even if you don’t see someone’s struggle, their pain or their decreasing health.

How to Start a Food Diary

Dear Diary,

Sometimes when I eat it feels like a herd of angry buffalo have taken up residence in my gut. The rumbling, the pain, and the regret are all too familiar at this point. Maybe I just shouldn’t eat at all. Maybe that would be best. I wish it could just stop…

Okay, I might not be talking about that type of diary, but I’ve had many days in my Crohn’s journey where that could have described me. Like many people with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), I have a frustrating mix of good days and bad days. It always baffled me how I could feel good one day, but terrible the next. I wanted to know why. This started my journey of paying closer attention to what I eat, and in turn, keeping a food diary.

Why a food diary?

Our environment is everything we come in contact with on a daily basis that isn’t us. The air we breath, the things we touch, and the food we eat all make up our outside environment. If nothing in our environment impacts a disease, it should feel the same every single day. For me, and many others with IBD, this just isn’t true. In this case, we must start looking at our environment as a source of triggers for our disease.

One of the largest parts about how we interact with our outside environment is what we eat. Every day we eat a variety of different foods, from a variety of different places, that have a variety of different health effects. For me, food was an easy place to start to try to figure out some of my disease triggers. I know what I am eating every day, so why not try to see if there is any connection between what I eat, and how I feel. This led me to food journaling, and it has been an invaluable resource in helping me navigate and manage my own disease. It has given me power.

Research also backs up this idea. In one study done in 2016, one group of Crohn's patients was told to exclude either the four food types they had the highest antibodies to, while the other excluded the four food types they had the lowest antibody to. The group that excluded the foods types to which they had the highest antibodies had significantly lower disease activity and significantly higher quality of life.1 We might not have access to antibody testing, but we can certainly try to figure out what foods are worsening our disease and quality of life.

How to write a food journal

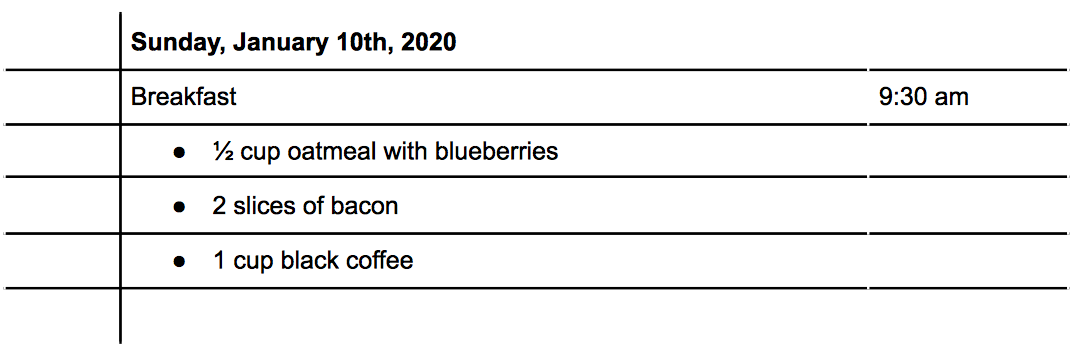

There are three main things to consider when writing a food journal: what you eat, the time you eat, and how much you eat. With these three written down, you will be able to better make connections between foods and symptoms. Let's do an example: For breakfast this morning, you ate a bowl of oatmeal with blueberries, some bacon, and a cup of coffee (I know, I know, coffee isn’t exactly known for its stellar track record in collaborating well with IBD, but it's a made up example!) How would that look?

Tracking Symptoms

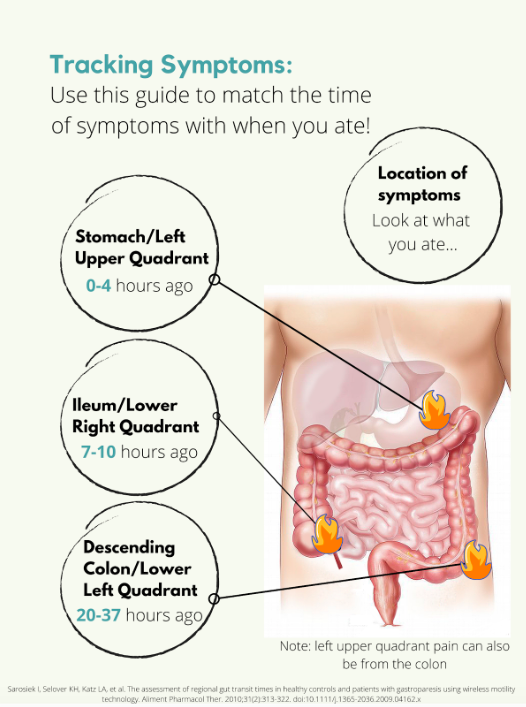

Symptoms are a little trickier. Say you have some pain in your lower right abdomen, how do you know what meal might have triggered you? Was it the meal you ate 5 minutes ago? 4 hours ago? The day before? For this we need to know a little bit about how long food takes to get to each different part of the intestines, also called the intestinal transit time. In a normal, healthy adult the following is accurate:

But what if you’re flaring? Diarrhea, inflammation, stricturing, and other aspects of a flare can all impact the amount of time it takes for food to get to the finish line. Some studies have been done on intestinal transit time in IBD patients, with most finding that the intestinal transit time is longer in IBD than in normal healthy subjects.2,3,4 In one patient with Crohn's disease, it took 156.2 hours for one meal to pass through. Talk about taking the scenic route! Like many other things with IBD, you are going to have to take an individual approach and problem solve to figure out how to best match symptoms and meals.

Resources

Tracking food can be done in something as simple as a spiral notebook, but there are also other options available. Here is a list of some apps you could use instead of a physical journal:

mySymptoms Food Diary & Symptom Tracker (Lite) by SkyGazer Labs LTD

Food Diary by WeCode Team

Cara Care by HiDoc Technologies

References

Gunasekeera V, Mendall MA, Chan D, Kumar D. Treatment of Crohn’s Disease with an IgG4-Guided Exclusion Diet: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2016/04/01 2016;61(4):1148-1157.

Andersen K, Haase A, Agnholt J, et al. P-113 Gastrointestinal Transit Times and Abdominal Pain in Crohn's Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2017;23(suppl_1):S40-S41.

Fischer M, Siva S, Wo JM, Fadda HM. Assessment of Small Intestinal Transit Times in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease Patients with Different Disease Activity Using Video Capsule Endoscopy. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18(2):404-409. doi:10.1208/s12249-016-0521-3

Haase AM, Gregersen T, Christensen LA, et al. Regional gastrointestinal transit times in severe ulcerative colitis. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2016;28(2):217-224.

Advocating for the Specialized Care You Need: Reflections on Mount Sinai’s IBD Clinic

Recently, I’ve started receiving care from the Susan and Leonard Feinstein Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Center at Mount Sinai. This was my first time visiting an IBD-specific clinic, ever. Prior to visiting Mount Sinai, I was lucky if there was a gastroenterologist or a colorectal specialist on call at my local hospital.

On my most recent visit to the IBD Clinic for a post-operation appointment, I thought I’d reflect on what made this center so special, especially during the COVID-19 era.

Post-surgery for an internal fistula -- feeling better already!

In light of the pandemic, the process for being admitted and seen (at any hospital!) has been streamlined into a tighter and safer protocol. With hand sanitizer stops at nearly every corner, I noticed that Mount Sinai took a heightened level of precaution than any other facility I had been in. Every doctor, nurse, and staff member had a face shield in addition to their masks, with some going as far as to don Bouffant caps.

Beyond the COVID-19 precautions, however, I would like to speak to the deeper and more important differences at this clinic -- the unspoken sense of solidarity between both patients and doctors alike. To have an entire facility devoted to this condition, a chronic illness shared by millions of Americans nationwide, means that there is a lack of cause to explain yourself. Everyone in the room is deeply familiar with the forms of IBD, along with all the embarrassing and critical details that few others are willing to talk about in their entirety.

The waiting room at the Mount Sinai IBD Center is all socially distanced!

This plaque, hung on the entryway of the floorwide clinic, is perhaps one of my favorite parts of the IBD Center. It’s a reminder of how fortunate we are, as young adults with IBD, to be treated in a time where our condition has been identified and researched, nevertheless with a name and prognosis. It is a strange feeling, indeed, to know that the work and medical achievements of this doctor (and his name!) has forever changed my life.

A plaque memorializing Dr. Burrill Crohn at the Mount Sinai IBD Center.

Of course, I would be remiss not to acknowledge how incredibly fortunate I am to live in the vicinity of this clinic. To have access to such a clinic with a focus on IBD in and of itself is a privilege, one that many Americans and patients are not so lucky to receive. I’m duly compelled, however, to point out how lacking our healthcare system is, especially for those suffering with chronic illnesses. As someone who was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in the summer of 2020, a time when the SARS-CoV-2 virus revealed the greatest inequities and vast underpreparedness of American healthcare, I’ve come to meet, learn about, and further appreciate the frontline and essential workers, who are simply making the most of what they’ve got.

Although it took me months to find the right team of doctors and healthcare professionals, I learned that it was alright, and at times, even necessary, for me to ask for more specialized degrees of care. An important lesson in my brief yet transformative journey with IBD: don’t be afraid to advocate for the specialized care that you need.

Reflections: The Importance of Advocacy for IBD

It’s a little strange to title this article ‘Reflections,’ because IBD is unique in that it’s always ongoing, with nothing to really jump over and look back on to reflect; with the journey still very much running, our reflections are inbuilt into it.

As I write this, I’ve been in remission from ulcerative colitis for more than a year. From the time I was accepted to be a CCYAN fellow to now, I have already been through a rollercoaster of new emotions: from immense gratitude and relief that I am finally a fellow of a network that I closely followed for several months to staggering self-doubt about whether I can truly do this opportunity justice. While poles apart, my feelings of gratitude and self-doubt and the largeness of the two do stem from the same root. After I was diagnosed with UC at the age of 19, I desperately needed to know more people who faced the same struggles. With little else to focus on in those starting years, hope would glimmer every time I found out about a famous personality or someone I knew who opened up about their chronic illnesses.

The way an invisible chronic illness creeps up on young adults is very much like a thief breaking in your house when you’re asleep and stealing things that don’t seem so valuable at first sight but without which you can’t really survive (like all your dishes). As young adults, we are so entitled toward our bodies and organs functioning properly that there’s no way to prepare or even know you will be impacted and when you do, people have very strong opinions on what you could have done to avoid it. And if, like some organs, dishes weren’t replaceable and the upkeep of the damages was constant, the last thing anyone would want is to deal with the struggle alone and keep it private. At least that’s how I felt. As soon as I was diagnosed, I let everyone around me know mostly everything except for the “impolite” specifics. Sometimes if the gravity of my situation wasn’t acknowledged, I would push to reveal the impolite specifics too. Concurrent to my health challenges, I was still also learning aspects of a broad society I had entered just two years before I got UC. As I rushed to speak and be heard, I realized, through the fear of my family and the discomfort of peers and friends, just how closed this society is towards these things.

When there are no voices for something that drastically alters every aspect of your life, it feels as though you’ve been dropped off to a completely new city with no maps for guidance. Maps are important for not only getting you from point A to point B, but also giving you a sense of orientation to gauge where you are with respect to everything around you. No voices = no maps. By far, in India today, invisible illnesses not only lack visibility in patients' external bodies, but also in national and private datasets, policies, and advocacy. This leaves patients disorientated and vulnerable to quackery (health fraud), which results in the loss of crucial time, finances, and deterioration of mental health (with the ups and downs of new hope and disappointment).

If the silence around personal disturbances was anything to go by, then I did not do a very good job of fitting in to my society as I always took the opportunity to talk about what I was going through even when I realized with passing time that it wasn’t always welcome or understood completely. I thought I should speak up all the more, because if no one does, who will vouch for me? This casual monologue took greater form in my first experience of being at a public hospital in my city. By that time, I had scoured the internet for people like me, experiences like mine, unique symptoms like mine, etc. I had come to recognize some feelings that came as a by-product of my illness through Hank Green’s videos on YouTube, and that the illness was bigger than me and my doctors (who only focused on the strict textbook aspects of IBD). My mom and brother very supportively drove and accompanied me for my sigmoidoscopy and I even got to sit as I waited for my turn. Waiting for countless hours after the scheduled time of my appointment, I was busy drowning in my pond of self-pity. When I heard a young lady slightly older than me was invited to go before me, I was very irritated and urged my mom to leave and reschedule. My experienced mother knew better. As I waited, I could hear the conversation between the young patient and the doctors in the room next door. She was a daily wage worker and her grumbles about missing work, her stomach pain (due to which she tilted sideways when she walked) and the tedious hours she spent waiting for her turn followed her into the room. The doctors didn’t indulge her in any sympathy, but rather curtly started the process. I wondered out loud why they hadn’t offered her a sedative – whenever I was asked, I always thought what a preposterous thing to ask when the process was so intrusive and uncomfortable. It was because she was alone and needed to hear the doctor’s findings and, of course, had to head back home alone. Even in my miserable state, that struck something in me. Her yells and shouts during the process, and the surrounding patients’ aloofness painted a picture so bleak, I was forced to look beyond my situation and recognize that despair like mine was still placed high on privilege. Granted that sigmoidoscopies are not the most pleasant of processes to go through or even prepare for, her shouts seemed out of place. I gathered it was more of a release from the anxiety of being alone and in such a vulnerable position with no emotional support. It took me back to a brief, mostly one-sided exchange she and I had before she was called in. From the little I understood as she spoke rapidly in her dialect, she had absolutely no understanding of the formalities of the prep that had to be taken and, more worryingly, the seriousness of her illness. She had two kids she had to care for, and she came alone because her husband was a daily wage worker who could not miss work especially since she was missing work that day too. She complained to me about the high prices of prep, all the days she had missed getting tests done and scheduling and rescheduling appointments in a government hospital, her appetite loss due to nausea and how she couldn’t perform her labor-intensive work as efficiently. After she limped out of her session, I thought of the sheer population of people like her in India.

Ever since that episode, I started thinking beyond my illness and what I could do to help the numberless amount of people in the same boat as the young woman. To start helping, the first step is to get a clear picture of how many people are impacted by IBD, which is frustratingly not available nor acknowledged anywhere in India. I am grateful, therefore, that I found CCYAN as an international platform for advocacy. Advocacy would hopefully enable data collection somewhere down the line. However, sometimes the mountain looks too big to climb; at this moment, we are right at the bottom and there are many things to do. Sometimes I think of all the people suffering from IBD in India, and how many struggles go undiscovered due to health illiteracy, digital gaps, doctor unavailability, and expensive medication, etc. Now more than ever, as cases of autoimmune disease rise across the world, there needs to be a prominent force of advocacy for IBD in India, so that datasets can be recorded and informed policies can be formed. The innumerable people who struggle already for a living should not be further hindered in their struggle for support, information or resources in this regard.

How Toxic Productivity Can Affect Chronic Illness

“The grind never stops” is a quote I’m sure all older gen-z and younger millennials have heard. Hustle culture is like the monster hiding under our beds just waiting to attack us the moment we dangle our foot off the bed. It’s the scary email we try to avoid, but eventually have to acknowledge is there. Our society places a great amount of pressure, on our generation specifically, to work hard and constantly strive for a lifestyle in which we are operating at an “optimal level”. This is deemed as success and this version of success should always be at the forefront of our minds and influence all decision making. Participating in this hyper productive hustle culture is difficult enough for the average person to achieve, but what does it look like for people that live with chronic illness?

To put it simply, living with chronic illness(es) is hard. Personally, it is the most difficult thing I have ever experienced. With symptoms like chronic fatigue, anemia, and anxiety etc., paired with frequent doctor's appointments and stigma, one could imagine that it is virtually impossible for chronically ill people to participate in hustle culture. Unfortunately, being in this generation makes escaping from the plague of toxic productivity quite difficult. Growing up we have all heard the stories of the business person working 60+ hours a week to bring his dreams to fruition. This mentality has influenced our entire generation. Working hard should always produce tangible results, right? Well, not exactly. As someone that lives with IBD, overworking myself can have dire consequences. Stress and anxiety are common triggers for people living with IBD, so it can be exhausting to focus on extracurriculars, staying social, maintaining good grades, and overall performing “optimally” while you’re inches away from a flare up. Our culture’s ingrained toxic productivity can be seen as the genesis of this behavior. I regularly catch myself being filled with disappointment that my illness prevents me from working at the capacity that I deem as optimal. Blaming myself for the pressures that our society puts on this generation only adds fuel to the fire, but never addresses the true issue, which is our ingrained idea of hustle culture.

As young chronically ill people, we must stay aware about never pushing our boundaries and our illnesses in the name of productivity. Productivity is a wolf in sheep’s clothing; it seems innocent enough until it comes and bites us, and that bite for many of us is a flare. It is never a moral failing if you aren't able to operate at the same capacity as your pre-diagnosed self or other able bodied individuals. As chronically ill people, we have so many unique challenges that we must acknowledge and honor. Here is a metaphor that I often remind myself of:

“We are all running a race, and some people are completing laps in 7 minutes, and others are completing laps in 20 minutes. Some may have to stop to breathe, sit and take a brief rest, or even leave to grab water, but the timing doesn't matter, the effort and intention does. All effort is valid.”

In the metaphor above, the race represents toxic productivity and the one’s completing the laps in 20 minutes who have to frequently stop represents chronically ill people. Giving into the pressures of hustle culture and toxic productivity will only reinforce the cycle. So, for the college student that lives with IBD or other chronic illnesses, such as myself, who is putting excess amounts of pressure on themselves to excel in every facet of life, try to be conscious of allowing yourself the space to rest and recharge. “Rise and grind'' is hard to do when the rising part is the issue. Glamorizing and internalizing the generational curse that is hustle culture and toxic productivity can cause irreparable harm to ourselves. Remember, work does not equal self worth.

So, when you’re in bed trying to get rest and all of your responsibilities and the ghosts of toxic productivity are whispering in your ear, try your hardest to ignore those voices, turn the other direction, and get that well deserved rest.

Intestine Resection Experience in an IBD Patient

Many individuals who face inflammatory bowel disease will require surgery at some point throughout their lifetime. There are numerous reasons why an individual may need surgery such as abscesses, fistulas, scar tissue, active disease, perforations and many more ailments. Through my personal experience, I would like to share some tips to help you prepare for your experience with intestine resection surgery.

My intestine resection took place during the month of June in 2020 due to scar tissue narrowing my ileum, as well as some remaining active inflammation. During surgery, my ileum and a section of my large intestine were removed and my small intestine was then reconnected to my large intestine through a laparoscopic procedure. Enduring a surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic led me to experience a whirlwind of emotions. To begin, my original surgery date of May 2020 was postponed; however I was lucky to be able to receive it in June. During this time, hospitals in Ontario prohibited any visitors for adult patients, so unfortunately I was unable to have any visitors during my hospital stay of four days. I was so incredibly nervous to undergo a major surgery for the first time and knowing that I wouldn’t have any in-person contact with my loved ones, made the experience even more frightening. I knew that I would have to be my own advocate while in such a vulnerable position, a daunting feeling that made me quite nervous. Despite the fact I had many fears, I am happy I underwent surgery. I have recovered and continue to feel better than ever. During my hospital stay, I was taken care of by my colorectal surgeon and a wonderful team of nurses, and although I couldn’t wait to return home, I felt comfortable and secure while recovering in the hospital.

Receiving a surgery as serious as an intestine resection can seem terrifying, and trust me - I was terrified. To ease my mind and fill me with the confidence I needed to undergo this procedure, I fully immersed myself in taking great care of my physical and mental health. Physically, I made it a priority to get extra sleep, stretch often, go for walks when my body had enough energy, and made sure that I was eating nourishing foods. Mentally, I talked about my fears with my medical teams and loved ones, saw a therapist to learn coping techniques and made it a priority to journal daily. I also carefully and strategically packed a hospital bag with items that I knew would bring me comfort and make my hospital stay as easy as possible. Below are the items that I used daily during my stay.

Hospital Bag Check-List:

Night gowns or oversized T-shirts (pack comfy clothes that don’t put pressure on your abdomen)

Loose underwear

Extension cord and chargers for phone

Face wipes (it will be hard to shower!)

3-ply toilet paper (hospital 1-ply toilet paper in the WORST)

Stuffed animal to cuddle

Cozy blanket and pillow case

Easy to put on slippers (you won’t be able to bend down and they are great for walking the halls)

Perishable snacks if you require a special diet (or don’t like hospital food)

Anything else that will bring you comfort or joy

Before my surgery, I was searching everywhere online to gain insight on what my hospital experience might be like and I was unable to find many resources. I hope by sharing my personal experience in an Ontario hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic will provide comfort and ease the nerves of other IBD warriors going through a similar experience.

The Day Before Surgery:

Remember the prep before colonoscopies? She’s back! The prep instructions I received were extremely similar to colonoscopy laxative prep, along with a large dose of antibiotics. Your medical team may prescribe you something similar or different. Either way, you’ve got this!

Hospital Check-In:

After arriving at the hospital and checking in, I was brought to a change room where I was asked to change into a gown and check my suitcase. After I had changed, I was brought to a pre-operation room where the intravenous was given. My biggest piece of advice while going through all of these steps leading up to the surgery is to express how you are feeling to your nurse and medical team. I was feeling extremely uneasy and expressed these feelings to my nurse and this prompted her to request an anti-anxiety medication from the anesthesiologist that I could take prior to walking into the operating room. Once in the operating room, I received an epidural. I was personally terrified of receiving an epidural, but I experienced zero pain from the needle! After that, it was easy. I was quickly put to sleep and before I knew it the surgery was done!

After Surgery:

Upon waking up, I felt extremely tired and out of it. I continued to sleep for hours until the nurses woke me up. They encouraged me to try to stand up and use the washroom to empty my bladder. Due to the epidural and medications I received, I felt minimal pain and my legs remained numb for a few hours. Although I did not feel as if I was in pain, I could make out feelings of soreness within my abdomen. Afterwards, I was left to rest and was allowed to start drinking fluids. My medical team encouraged me to eat the next day and I brought snacks for this specific reason.

The first three days after surgery were the worst for me in terms of pain. As someone with IBD, I was accustomed to experiencing severe pain and I was able to control this pain with only Tylenol. I’ve previously been prescribed narcotics to control the pain associated with my IBD flares, so only needing Tylenol was a win in my books! My surgeon cleared me the day after surgery to begin walking the halls and moving my body. Walking was exhausting and caused me pain but it truly helped out a lot with my recovery. I was only able to stand and walk hunched over to avoid putting pressure on my abdomen which I still can’t determine whether my mind was protecting my body or if I was really unable to stand straight. This continued for about a week and each day I was able to stand up a little taller.

Returning Home:

Once I was cleared to leave the hospital, I returned to the comforts of home where I was able to have my family care for me. Stairs were unbelievably challenging and I needed support to get up and down. I was extremely exhausted for a couple weeks post-surgery and majorly prioritized rest and recovery. My biggest advice is to have a caretaker for your first few days back at home, to help you get in and out of bed, cook meals, and shower. If you are going to be alone, sleeping on the main floor and pre-making meals before surgery would be extremely beneficial to ensure you have easy access to nourishing meals.

I found it extremely difficult to get in and out of bed - I never realized just how much I use my abs! I recommend setting up a sturdy piece of furniture by your bed, such as a chair or side table, to use to lift yourself up and out of bed with. I also found that sleeping in an upright position was much more comfortable, putting less pressure on my abdomen, causing me to stack my bed with pillows.

Please remember, it can take some time for your body to adjust to the surgery and notice results. Since I had a narrow ileum that caused blockages and poor digestion, I thought I would immediately have better digestion after surgery. My digestion is a thousand times better as I write this, but it took about a month for me to truly notice any of the improvements and benefits from the surgery and continued to notice additional improvements months following. During this time of recovery, each day my body continued to become stronger and more resilient.

I hope my personal experience receiving an intestine resection will help those of you who are preparing to undergo your own intestine resection. My hope is the advice I have given you will help relieve your nerves and guide you through the process, by giving you a better idea of what to expect. As members of the IBD community, we are strong, courageous and resilient!

An Ecosystem of Advocacy

My fellowship at CCYAN is coming to an end. Coincidentally, I have felt short of ideas these few weeks. I’m writing this one late, partly because it has taken me a long time to fully recover from COVID, and partially because I was torn inside my head about what I wanted to say. Lately, my brain has felt like a cauldron with a stew of thoughts in it. I had been hiding safely in my home from COVID, but now that it got me, it’s time for me to go back to my pre-covid life.

At the time of writing, I’m about to fly back to my campus. I had deferred my exams for the previous semester hoping that the pandemic would settle down by Sept/Oct. That did not happen. I have lost a whole academic year. I now need to work twice as hard to get my degree. The pandemic has also doubled my healthcare expenses, and hence I need to work more than usual, which decreases the time I can devote to my academic work. I have also not been to the doctor in more than a year. After a long time, I have once again felt the fear of things going wrong and beyond my control.

One of the things that I’ve come to realise and feel in recent days is how isolating IBD can be. IBD symptoms can vary from person to person, but when you look at those symptoms in conjunction with life experiences, every one of us is on a very different path and fighting a very different battle. It is true for every chronic condition. One community, one group, can never be the answer. We need multiple communities composed of people with diverse experiences to thrive and work with each other. An ecosystem. Without that, there’ll always be someone feeling alone in their experience.

I have always been someone for whom repressing is more comfortable than expressing. Does that not make me inadequate for the job of a patient advocate? Repressing pain and trauma has enabled me to survive. The goal of life shouldn’t be to survive, though. I have compromised on every other aspect of my life so that every day I can do enough to stay on track with my goals and ambitions. Some compromises must be made, but some are forced upon by circumstance and external agents.

In the ancient world, people believed that the sick were cursed by gods. Treatment consisted of praying and giving a sacrifice to the gods. The ill thought that they were cursed. They were killed when the gods didn’t pay any heed to prayers. You might think times have changed, but they haven’t. Too many of us have been told that our illness is punishment for our past sins. Many of us believe it also, so much so that a patient recently said to me that their experiences didn’t matter because they were not good experiences. India is a country where the concept of “invisible disability” is yet to be introduced. In such an atmosphere, people with chronic conditions and invisible disabilities are forced to compromise. After all, it’s practical and easier for everyone. Any ill person that “complains”, does not radiate positivity and inspiration is useless. The attitude in general, towards sick people in my country, reminds me of the phrase - “Ignorance is bliss.”

So if you’re chronically ill - not only do you have to make compromises in various aspects of your life, not because they should be made, but because it’s comfortable for everyone else, you also do not have access to communities where you can share your frustrations, your experiences with people facing similar, if not the same set of circumstances.

Some say that we should not highlight our disability. Some argue that many people are successful with Crohn’s Disease or Ulcerative Colitis, but they do not talk about it. Talking about it is just asking for pity. The people who are going to succeed will succeed despite it. Such thinking patterns stigmatise our illness and strengthen the notion that patients are the problem, not the illness. Patients are not doing enough; others are.

As with everything else, things will not change unless we accept that there is a problem and that there is a real need. The irony in India is that those with voices do not have the need, and those with needs do not have a voice. There is an urgent need to build communities that provide support and advocate for better solutions.

I often feel that I say the same things every month, but I also feel that these things haven’t been said enough times. So to my fellow patients and the people who understand our needs - keep speaking up and keep talking, until our voices are too loud to ignore.

Thank you. Stay safe.

A Capital Mistake

Disclaimer: These are my views and observations, based on my experience with online Inflammatory Bowel Disease support groups in India.

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

~ Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes

When I began my fellowship at CCYAN, I was a stranger to patient advocacy. I had a very vague idea of what the word meant. A couple of months later, I began a local initiative to explore the possibility of building a patient advocacy group for the Indian IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) population. I started by imitating and trying to replicate the actions of existing advocacy groups in the US and the UK. However, it didn’t work. I soon realized that there is a larger fundamental problem that has to be addressed before I speak up for anything. It is the problem of patient education and health information.

Patients in India are far less aware and informed about their condition than patients in the developed nations. A higher rate of illiteracy, language barriers, lack of counselors, and short consultation times are major reasons. While it may seem that this problem can be rectified easily by disseminating educational materials among patients in various ways, the reality is that the void created by a lack of information is not a void at all. My observation is that the void has been occupied by incorrect and unsubstantiated information that prejudice a patient’s mind when it comes to learning and accepting correct, evidence-based information about their condition. This “defect” in the knowledge that a patient has about their condition can lead to deterioration of their condition and, in some cases, prove to be fatal.

The lack of patient education itself is a mechanism through which misinformation spreads. Existing patients with defective knowledge pass it on to the newly diagnosed. In the absence of rectifying sources/agents, such information can propagate and spread among groups of patients - very much like a virus. One of the places where things go “viral” is social media. The networks that connect us all are one of the pathways through which information that has no factual basis propagates.

In India, we have a small, but a fair number of Facebook and WhatsApp groups of patients suffering from Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Members of these groups exchange information daily on various topics - meds, diets, exercise, doctors, etc. I observed that there is a small subset of people, not always, but usually the creators of these groups that influence these discussions. This subset of people also acts as a source of “information” and “knowledge” for the other members.

In my experience, the majority of the discussions revolve around food and alternative treatments. Sporadically, there might be a discussion on the unaffordability of biologics, the struggle of young adults with the condition to get a job, study, or get into a relationship. However, these discussions are limited to a few comments, and that’s it. Several topics are not discussed out of shame. Erectile dysfunction because of IBD/surgery, anal dilation, rectovaginal fistulas, marital problems, reproductive issues - these are just some of the few issues that people seldom discuss in these forums. A support group is supposed to be a safe space, but these groups don’t feel like one to me. Nobody feels safe about opening up on problems that affect them very much because of fear of judgment and shame. The “advocates” too, rarely take any initiative to remove the stigma and taboo. We, the patients of India, with our ignorance, play a major role in keeping the taboo and stigma associated with IBD intact. The creators and moderators of such groups rarely take care to protect the newly diagnosed from misinformation. Many even float their own theories and post uncorroborated information.

A year ago, the mother of a 31-year old patient called me. She was crying. She asked me to visit her son and counsel him. I received her call a couple of weeks after I had moved to Bangalore for my graduate studies. I was unsure, but I went to her home and visited her son. He was lying down on the bed, with a heavily bloated stomach and a hot pack on his abdomen. I started talking to him. He told me that he had been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease 7 years ago. Initially, he was prescribed Pentasa, which he took for two weeks only. He did not feel that he was responding to the drugs, and hence, he stopped taking the medication without consulting his doctor. He never visited his doctor again.

On the advice of “advocates” and “experts” on the internet, he began buying and consuming naturopathy products, special brands of water with a certain pH, and many other products that he claimed were alternative medicine. He was importing many of these items. When he ran out of money, he borrowed money from people on the pretence of treatment and bought the products. He hadn’t seen a GI in 6 years! He showed me the results of a 3-year-old imaging test. It mentioned internal fistulas. He could not even stand up. His old mother was caring for him. Sometimes, when he would be in a lot of pain, his relatives would take him to the emergency room where he would be advised immediate surgery. He had been refusing the option of surgery every time. I spent an hour trying to talk him into surgery and explaining that an ostomy is not the end of the world. He wouldn’t budge. I returned - disappointed and angry. A few days later, I received a message from him. It said that he did get a temporary ostomy, but he’ll be going back to naturopathy to save his colon. I wished him all the best and urged him to act responsibly. I never heard from him again.

This person was ready to die instead of accepting treatment from a doctor in a structured and safe manner. He spent his time lurking on the internet in such “support groups,” where he learned various expensive and ineffective remedies for his condition and went on to irrationally and blindly pursue them. He could have avoided the surgery, had these very “advocates” told him to get back to his doctor.

Let me clarify here that I’m not speaking against the use of alternative therapies, some of which in recent times have been supported by some studies as a good supplementary treatment option. I object to disseminating unsubstantiated information in a manner that evades judgment, analysis, and scrutiny. Science, rational thinking, reason, is how humanity has come so far. It’s the gift we have—our capacity for reason and imagination.

Modern medicine does not fully understand inflammatory bowel disease and many other conditions. This, in turn, has become an opportunity for some people to form and present their theories which are either completely unscientific or based on some science, but completely opaque to scrutiny. These baseless theories and cures are dangerous. Desperate patients often end up losing a significant amount of money, time, and health. Such theories and their preachers often evade accountability.

We can only fight something well if we know what we’re fighting against well. I feel that most IBD patients in India are fighting blindly. The larger population of IBD patients in India faces a wide variety of problems compared to the handful of patients who have the luxury to engage in comfortable discussions in closed spaces on social media. Those problems are rarely discussed and confronted.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease is a complex disease. Good communication is the first step towards helping patients navigate the physical and emotional roller coaster that comes with having an illness like IBD. We must develop a culture of sharing medically verified and factual information amongst ourselves. It’ll help create a community where everyone is aware and informed. The newly diagnosed, who are often confused, shall receive appropriate guidance and support. Only then can we begin to speak up as a collective voice for matters that can help improve the quality of life of Indian patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

That’s all from my side this month. Stay safe :)

The Difficulty of Finding a Treatment

For the ordinary individual, health is accepted as a given. It’s a part of life that mostly runs in the background like a minimized window on a computer. It’s always running, keeping us alive, and impacting our physical and mental states. Yet again, for most people, it’s rare to directly confront it on a minute to minute, or even second to second basis. Instead, it emerges at the forefront of life either by active and deliberate personal choice, or when something goes wrong. When a previously silent computer program running in the background becomes unresponsive, what was once insignificant becomes a major issue. To a greater extent, when that disruptive program causes our computer to crash and lose all of our work, it’s catastrophic. In a similar way, the typical individual goes to the doctor only on the occasions when their health is compromised by infection, injury, or other issues. Plus, when our health is stable and we are well, the changes we make, like starting a fitness regime, new diet, or implementing mindfulness strategies to our lifestyle, are done by choice.

However, when you live with a chronic illness, health management becomes significantly more complex. For one, chronically-ill patients often do not have the benefit of having a lifestyle defined by stable health. Chronic illness is by its very nature unpredictable. Diseases like Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis revolve around periods of peaks and valleys - remission and flares. Once again, living with a chronic condition transforms the nature of managing health. The process of searching for, utilizing, and adjusting to a treatment for inflammatory bowel disease, or other chronic conditions, is one of trial and error. Unlike treating the common cold or a broken bone, the path to recovery is much less clear cut. Personally, I have tried various medications across a variety of different medication classes only to discover that they were not effective for treating my particular case of ulcerative colitis. It takes constant monitoring of your symptoms, and a commitment to embracing change to successfully navigate the healthcare system as a chronically ill patient.

It’s a difficult reality that many patients struggle through countless medications, clinics, and treatments before finding relief. Simply put, when you live with a chronic illness, your health is never certain. It’s unlike managing short-lived, common conditions, because there’s no clear timeline. Patients are forced to adjust to a new normal. This new reality is a reality where an individual must persist despite burnout, despite anxiety, and despite certainty. It involves significant sacrifices in one’s lifestyle, and even identity. Confronting health is no longer a special event or a choice, instead it’s a part of the daily routine. I believe this is part of why accepting illness is full of so many emotions, and why fatigue can easily take over. Everyday, patients are fighting a difficult, and often invisible, battle while living normal lives full of other responsibilities. The process, and the challenges, involved with finding and managing treatment do not make this balancing act any easier. Thus, it’s important to recognize the difficult, frustrating, and exhausting experience of patients worldwide. After all, despite illness, set-backs, and struggles, we persist to live lives as friends, artists, and advocates.

How My Mental Health Was Affected by IBD

Mental health has been on my mind a lot lately. From hearing it in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, to having conversations about the need for more resources for IBD patients, to dealing with my own experiences with depression and anxiety - mental health resources are perhaps one of the most underrated and underfunded sectors of healthcare. I realize this as I’ve gotten older, immersed myself in the medical field, and as I have utilized it for my own mental health after being diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) in 2016.

I bet many of you have also dealt with IBD affecting your mental health whether you realize it or not. For most of us, we were the only person we knew who had IBD at the time we were diagnosed. Some of us may not have even heard of it until we were told after our colonoscopy or endoscopy. The world around you suddenly feels a lot busier and bigger, and you feel very small and alone. Alone, wrapped up in your thoughts, your pain, your exhaustion, your fear. None of us asked for this. What did we do to deserve this?! In the days after my colonoscopy, this thought permeated my mind and I wanted to curl up in a ball and wish it all away.

But, you can’t do that when you are a busy pre-med student working full time and taking classes! We are expected to stay strong and keep up our front that says “Everything’s fine,” when, in fact, we’re not. I had great people to talk to and that would listen to me, but I still went through a mourning process. I mourned my life before when I thought I “just had a sensitive stomach.” I mourned that fact that my diet would probably change and change again and that I maybe would have to be on immunosuppressive medication. I dreaded the future conversations that would come up when someone would ask why I had to go to the bathroom so much or why I couldn’t eat or drink something. Really, everything’s fine…

But, it’s not. CHRONIC is a word that I hoped never to hear in regard to my medical history. We now have a new label that we must carry for the rest of our lives, and it’s anything but predictable. We have to explain this diagnosis so many times we feel like it might actually define us. The reality of my UC diagnosis began to truly sink in and anxiety began to seep into my daily life. My energy and concentration was poured into reading about UC, finding a better “diet”, looking for tips on how to achieve and stay in remission, and finding some kind of outlet for my anger and frustration.

Honestly, I should have given myself a little more time to process and try to seek the help of a mental health professional. Now, I think, I should’ve thought about my IBD and mental health together rather than separately. I let myself have a little time to mourn my UC diagnosis, but I thought I needed to be strong and keep my diagnosis to myself, much like others had before me. If we don’t look sick, perhaps no one will know. Even when we try our best to be strong and adapt to this normal, our mental health often still ends up suffering.

I think it would make such a positive difference in the lives of so many if we are all equipped with a medical and mental health treatment plan after being diagnosed with IBD, because the fact of the matter is that the mental health symptoms are just as debilitating as the physical symptoms of IBD, and they’re often intertwined. We need this kind of support as we manage our diagnosis - which sometimes can land us in the hospital or needing major surgery. I can’t speak to these kinds of experiences, but they can be traumatic in their own ways. How many failed medications or pain does one endure until they receive a potentially life-changing surgery? Thinking of the mental health hurdles that my co-fellows have dealt with and shared so vulnerably leaves me in awe of their strength. When they share what they have lived through, it also makes me sad that there was not adequate mental health services available to some of them when it could have offered an outlet for some of their pain.

Even now, almost 5 years out from my diagnosis, I take medication for my depression/anxiety and have re-established a relationship with a counselor that has experience in treating clients with chronic illnesses. I still go through the peaks and valleys of life and IBD, but, now, I’m better equipped to handle the lows when they hit or when a flare affects my mood and interest in doing things. I want the mental health support that has been so instrumental to some of my healing to be more accessible and affordable for those with IBD in the near future.

I hope speaking candidly about mental health and sharing some of these reflections helps you feel less alone and more validated in what you’ve been going through. The process of untangling all of these emotions is normal when grappling with a chronic illness diagnosis and what that means for you and those you love. Everyone processes major life changes and trauma differently, but don’t be afraid to ask about mental health services when you see your GI or primary care provider. Finding the right mental health support could be the treatment you never knew you needed.