By Isabela Hernandez (Florida, U.S.A.)

Going on prednisone is a somewhat universal experience for IBD patients. Maybe not everyone, but a lot of us have cycled through steroids and experienced the “fun” symptoms it brings along with it. One of them being moon face. Moon face is when your face appears very swollen and round. For me, I’ve cycled through high dose prednisone many times, especially in my childhood and have a very familiar relationship with moon face.

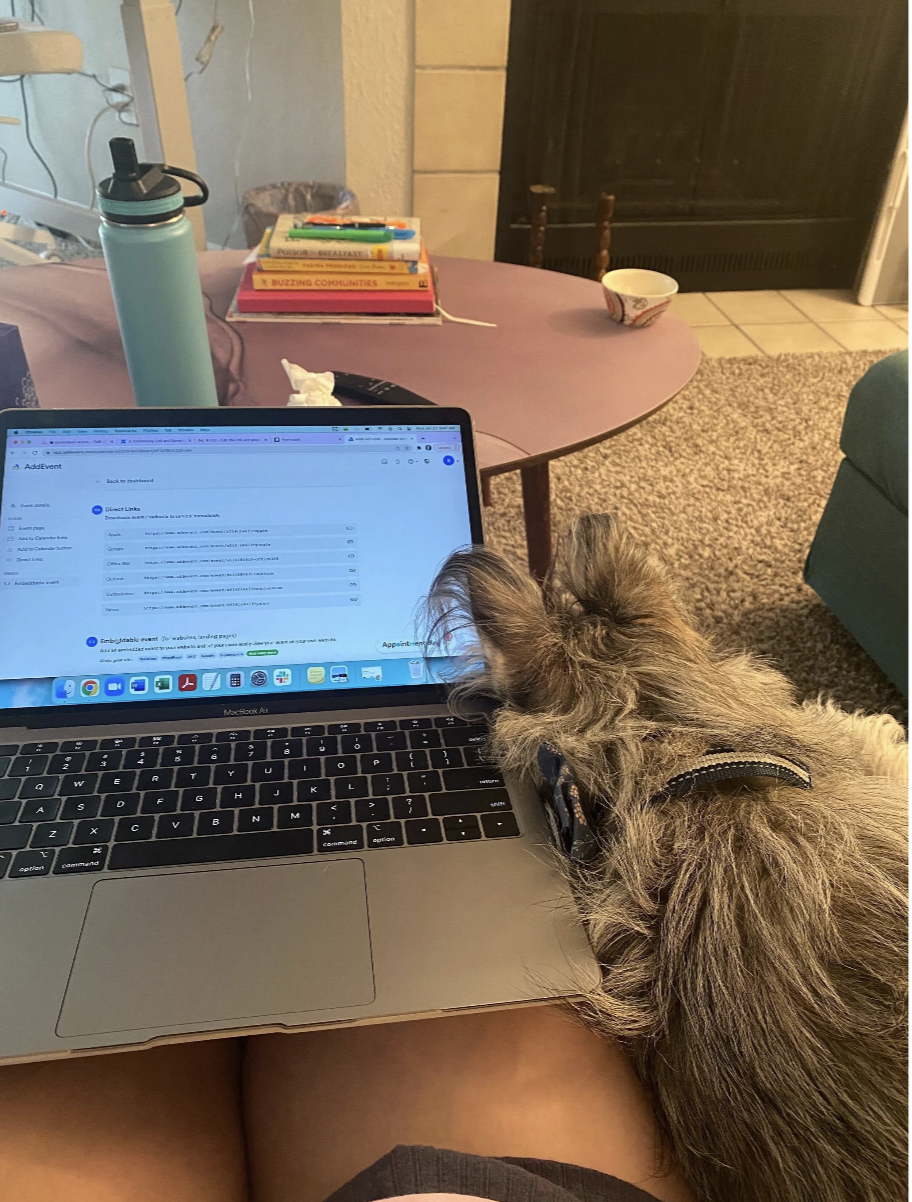

This was the first year I experienced having moon face. I was 5 at the time; I remember this time in my life vividly, especially this picture. It was a school picture day, and I knew we would be taking a lot of photos. I still didn’t fully understand what was going on with my body and even thought having IBD constituted as normal, as it was the only life I’d ever known. But what I did know was that I didn’t look like how I once did, that person that my classmates knew me as.

To compare, this was me the year before. I knew the girl in this second picture. That was me. But I didn’t recognize the girl in the first picture and would look in the mirror as a 5-year-old girl, confused on who was staring back. At the time, I didn’t realize how this would affect me later growing up. My relationship with my body and how I viewed myself every morning when I looked in the mirror was slowly tainted.

This was my second time having moon face. I was 8. I was a little older and much more self-aware about how others viewed my appearance. I became shy, closed off, and scared that my cheeks would scare my friends or cause them to not even recognize me. I remember thinking I didn’t even care about feeling sick inside or having to go to the hospital; the only thing I ever wanted was to look like myself and look normal.

This was my third time having intense moon face in childhood. I was 10 here. This was the worst for me. I was growing into my body, but the body I was growing into felt foreign. This was the age that my thoughts began to center about how I looked and how others viewed my appearance. I felt like the person I was inside and the person I saw in the mirror were two different people, constantly disconnected. I grew into teen hood and young adulthood with the same thoughts always seeping in. The constant weight fluctuations as a child constantly made me second guess how I felt about myself. No matter what weight I was at, when I looked in the mirror, the little girl with chubby cheeks was always the one staring back. This body dysmorphia never let me feel content with my body. I was in a continuous fight with myself, and I was always losing. Over time, and as I matured more, I tried to combat this. It became routine for me to constantly remind myself that the struggles with my body were caused by something out of my control. It wasn’t my fault, and I can’t punish myself every day for something I didn’t do. What I can control is how I speak to myself when I look at my body. My relationship with my body isn’t perfect and I don’t think it ever will be. I now just view those photos as different versions of myself, versions that were strong and resilient to the pain that IBD can cause. I need to constantly remind myself that my body isn’t my worst enemy and to control my thoughts when I begin to believe that it is. It’s easy to hate on our bodies and hate what IBD has done to them, believe me, I do it all the time. But I must remember that even though my body is not perfect, it’s the vessel that keeps me alive, doing the best it can, and that’s ok with me.

This article is sponsored by Trellus

Trellus envisions a world where every person with a chronic condition has hope and thrives. Their mission is to elevate the quality and delivery of expert-driven personalized care for people with chronic conditions by fostering resilience, cultivating learning, and connecting all partners in care.