NEWS

How Writing Helped Me Come to Terms with My Chronic Illness; How Finding Your Thing Can Help You Come to Terms with Yours

By Rachel Straining

As I’m sitting here now, I’m writing this in the notes app on my phone.

I remember in high school when we had to write our college essays. Mine came to me at 12 o’clock on a random Tuesday night as I was trying to fall asleep. I couldn’t shut my brain off, which is usually a thing that tends to happen to me in the very moments when all I want to do is shut my brain off. I knew I’d have to get my thoughts out somehow, otherwise they’d consume me to the point of no sleep. I rolled over and grabbed my phone from my bedside table. I opened my notes and watched my fingers tap, tap, tap as my mind led the way. I wrote the first draft of my college essay that night on my phone.

Now, as I sit here, writing this on the notes app on my phone, I can’t help but think about how finding a way to put my thoughts into words has changed my life and helped me come to terms with my chronic illness.

When I was in 4th grade, I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder. I had a hard time articulating my feelings. I would cry, a lot, but I wasn’t able to explain, or even understand, the “why” behind my tears.

I was put into therapy and eventually handed a pen and paper. A narrow ruled notepad that didn’t feel so narrow at all. Rather, it felt like an open, honest gateway into a mind that at times felt all too confusing to make sense of.

If I was upset about something, I would write it out. If I was upset at someone, I would write them a letter. Whether or not these words were ever shared was up to me, but the simple fact that writing gave me a way to process and work through my emotions was something I never had - something I wanted to hold onto forever.

Then, when my world was flipped on its axis and I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, I stopped writing. I stopped talking about how I felt and I stopped writing about it. Even though every piece of me was breaking inside, I wanted to forget and pretend like I didn’t feel anything. Everything hurt. My heart ached and so did my body. I wasn’t numb at all, but I wanted so badly to be. So, in an effort to try and shut everything off and shut everything out, I put down my pen, threw my paper into the trash, and forced my heart to go cold to freeze time.

I didn’t process the fact that I was chronically ill. I refused to. I studied or drank or exercised or ate away my emotions. I suppressed any kind of feeling, any kind of pain, any kind of grief, letting my emotions build up inside of me like a volatile eruption just waiting to happen and destroy everything within its wake. And then I flared my sophomore year of college and there was no way I could continue down the life path I was headed if I wanted to have a chance at living.

I found an old notepad in one of my drawers that year and I watched the life before me change as I began to use my words again. I watched myself begin to open up again, no longer bottling up emotions that so desperately needed to be let out, no longer letting things eat me away inside until I felt so hollow that I became a shell of a person. I watched myself begin to connect with others by using words to which they could relate as a way to bridge the gap between loneliness and understanding that had once felt too scary to cross. In writing, not only did I find my true passion, but I also found my true acceptance.

Especially when living with a chronic illness, one of my biggest pieces of advice is to find that thing you can turn to when you need it most. Something that will always be there for you, even when you try to push it away. It doesn’t have to be a person and it doesn’t have to be a tangible possession. Just something. For me, it’s sentences and paragraphs and poetry and prose. It’s putting my thoughts onto paper, or onto the notes app on my phone, and finding solace in the way writing helps me make sense of my truth when I find it too hard to verbally speak.

Whether it’s the way a good song can make you feel heard or the way a good book can transport you to a different place, we all have something. We all have that one thing that both steadies and ignites our heart. When you hold onto it, and when you harness your power through it, you’ll start to feel like you can finally take on the life that stands before you - one word or one note or one story at a time.

Navigating Diet Culture with IBD

By Amy Weider

Growing up food was always a celebration for my family. Food was how and why we would come together and build traditions. We would eat lobsters for every New Years to signify good luck and we'd come together to break the claws and soak them in butter. I remember watching my mother make us a classic midwestern casserole on a weeknight and the Food Network was never not on in the background. Food has always been such a critical part of my life. It brings me joy and memories. So when I started getting sick around 9 years old my relationship with it was forced to change. I began to have severe stomach pains and was unable to hold any food down. The first instinct when someone is having intestinal issues is to always investigate diet. My loving mother quickly made the switch to all-organic everything, bland food, and no more sugary drinks. At 10, I very quickly had to change what I ate and go on intense diets. It was hard for me, as food is such an important part of my life and a means of joy. But nevertheless, my family supported me through it and we went through the motions. Gluten-free for a bit, dairy-free, liquid-based only, we tried it all.

Alas, nothing worked. I was still, if not more, sick and constantly exhausted. Once the diets failed, I was given a colonoscopy and ultimately I was diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease. My Crohn's Disease was not fixed by a diet. In fact, no Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)is caused or cured by food. Diet can help with inflammation or regulation of the disease, but diet also affects every IBD patient extremely differently. Most often, this is not how it’s portrayed and it’s hard for folks with IBD to carry the weight of the assumption that there is a one-size-fits-all cure. Ever since I first became sick, I have had people tell me constantly that if I ate a certain way I'd be fixed and that it is my fault I developed such nasty health problems. Hearing these things as a kid made me aware of diet culture very early on.

Diet culture is the world we live in. It is everywhere. Diet culture can be defined as the patrolling of people’s weight under the guise of health, while it is really about control, shame, and reinforcing eurocentric skinny body standards and eating trends. Concrete examples of diet culture are folks labeling certain foods as “good” or “bad”, or the shaming of others for not eating the “right things.” Diet culture and the weight-loss marketplace is a $70 billion industry. There is no way of avoiding these harmful tactics of major companies marketing off of your body’s imperfections and longing to achieve the societal standard of a femme body. It becomes very difficult to balance the thin line between diet culture and a change in your nutrition for your health’s sake. Specific diets that are used to help manage IBD are often glamorized as the “new, hot trend that will make you drop ten pounds quickly!” There needs to be a greater understanding of how privileged it is to merely treat these diets as fads. They are often highly inaccessible, expensive, and fail for those who are just casually attempting them. But for others, for example those who have Celiac, this isn’t an option for them. There is so much nuance that is frequently overlooked when prescribing diets and there needs to be more attention given to diet vs. health and nutrition. The mask that is diet culture can very quickly take over one’s life.

When you Google “Crohn’s Disease” you cannot miss the slew of diet suggestions for anti-inflammatory foods or titles like “Gluten-free Fixed My Life!” Hearing people make statements like “you could cure that by eating ‘blank’,” has become a huge trigger for me. My relationship with food has had its rocky times, but it’s still a place I find deep comfort. Comments like these stem directly from diet culture and the invalidation of lived experiences. There is no right way to have Crohn’s Disease. Everyone’s life experiences differ greatly and the main lessons I’ve taken away from mine are to be open, ask questions, and not push assumptions onto others. Open a space for folks to guide a conversation about their dietary restrictions and needs if that’s what they want. NEVER suggest a new diet to an IBD patient unless you are their medical provider. Trust me, we have heard everything.

5 Things I Have Learned from Life with IBD

By Samantha Rzany

Living with diagnosed ulcerative colitis for about a year and a half now, I am realizing that I have learned quite a bit from this journey. While I often wish I did not have UC, I am grateful for the opportunities and growth it has provided for me. I do not believe that I would be who I am today without having to go through the struggles that stem from being chronically ill as a young adult.

Your health is one of the most important things in your life.

It is more important than grades, or accolades, or how many social outings you can go to each week. As a perfectionist who constantly strived to push myself to do my absolute best and be my absolute best, the concept of all of those things taking a back seat to health was really difficult for me. But when you are at your sickest – in pain and in and out of doctor’s offices and hospitals, you quickly learn to appreciate the days and weeks when you are healthy. And working to maintain that health becomes a higher priority. For me, I had to realize that other things were less important than feeling physically and mentally good.

Don’t push yourself.

Your body is already working double to do the everyday things that healthy individuals take for granted. Your body fights so hard to just get up and do normal day-to-day things. It has to work so much harder than a “normal” body to do “normal” activities. Oftentimes, you will feel fatigued after simple tasks. You might not be up for things that your friends are capable of. You might know you can’t eat certain things at places your friends may want to go. And it is hard to not want to push yourself to do these things in order to keep up. But you don’t have to push yourself. You don’t have to convince yourself you may be fine if you try this, even though the past 10 times you weren’t. Which brings us to the next lesson…

Learn how to say no.

There will be times you can’t eat certain things or can’t do certain things. And that is perfectly okay. Good friends and family will understand that and not treat you any differently. But sacrificing yourself to please others is never necessary. You’ll have days when you are too tired or too sick to do certain things. And that is perfectly okay!! Certain friends or family members of yours might not understand. They might not accommodate you or the things you may need. But the people who love you and are kind and understanding will work to accommodate you however you need. They won’t be offended when you have to say no to things. Some might even try to find other activities or restaurants that you are up for! These are the people you want to keep around. But there is no shame in having to say no to people or activities. Saying no means you have enough self awareness and understanding to know what you can handle.

Know your limits.

You have to learn what you can and can’t do – both when you’re flaring and when you’re in remission. Know what you can eat, how often you can go out, and how much you can do every day. You will have your limits. And those may change every week or every few days. They certainly will change between when you’re healthy and when you’re sick. And it’s important to work to keep track of what those limits are. It may mean only going out once or twice a week and getting together with friends/family at your place other days. It may mean not being able to go to certain restaurants when you’re flaring because you can’t eat anything there. It might mean feeling up to go out and being an hour into it and feeling too tired or sick to keep going. All of that is perfectly fine! You just have to know what your body is capable of and not compare that to anyone else.

And most importantly…

Give yourself grace.

There will be days you’ll get frustrated. You’ll be sad and angry. You’ll be hurt by how people respond and sometimes you might just want to feel normal again. But you have to learn how to give yourself grace. Your body is capable. Even when you were at your sickest, you made it through. You are strong and brave. And you need to give yourself grace. When you have to say no to things or aren’t feeling up too what you used to be able to do, you have to give yourself some grace. Comparing yourself to others your age will never be beneficial. Instead, remind yourself of how strong you are and how much you have overcome. Allow yourself to put yourself first sometimes and make your health a priority.

Hair Loss

By Rachel Straining

Hair loss was something I never expected at the age of 22 until I found myself staring in the mirror, crying at my reflection.

I knew the stomach pain. I knew the sharp, stabbing aches. I knew the nausea. I knew the fatigue. I eventually even knew the PTSD. But I didn’t know about the hair loss.

Telogen Effluvium, they called it. It took me a while to figure out how to spell it let alone understand it. Telogen Effluvium - the medical term for temporary hair loss that occurs after your body undergoes serious stress, shock, or trauma. The words stress, shock, and trauma barely begin to cover what my body went through almost a year and a half ago.

When two of the worst flares I’ve ever experienced happened back to back, one after the other, I lost weight rapidly. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep. I could barely breathe. I could barely even make it up the stairs without holding on to the railing for dear life and support.

Shortly after, that’s when my hair started to fall out like I’ve never seen it fall out before. In clumps. In the shower. In my hands as I held seemingly endless strands of hair that I never thought I’d lose.

I have always struggled with feeling beautiful in my own skin and my own being. Truthfully, growing up, I had always placed an immense amount of importance on my appearance, and my long locks had always felt like a kind of comfort blanket. “Hey, at least I have good hair,” I would say as I picked every other inch of myself apart. Watching my brittle hair fall in my boney hands as I stood in the shower with hot water and tears streaming down my face felt like the final blow to my already withering self-worth.

I wouldn’t put my hair up. I couldn’t. Not in a bun, not in a ponytail. No matter how hot outside it was or how humid it got. If I tried to, I would immediately break down at the sight of empty, bald patches of hair that were once so full.

Hair loss is not something that many people, especially many young adults, talk about, but it’s something I’ve come to realize that many have experienced. It is an external, physical side effect that also comes with its own host of internal, mental battles.

You can say it’s “superficial” and you can say hair “doesn’t matter,” but when your illness continues to distort your self-image and self-confidence time and time again in ways you never thought imaginable, it is hard. It is really hard. It is traumatizing. It is difficult to fully understand unless you’ve been through it. No feelings we endure are trivial, no battles are to be invalidated.

As someone who has gone through it herself, I am here to tell you you are allowed to feel it all, and anyone who says otherwise can come talk to me. You are allowed to be angry and sad and upset. You are allowed to cry, you are allowed to mourn what you once had, but I also want you to know that I refuse to let you give up on yourself.

In the moments when you’re standing in front of the mirror or standing in the shower, I know how much of a battle it can be to feel good about yourself, to feel like yourself, to feel like you are complete with bare patches revealing your skin.

However -

In a society in which it has been so wrongly ingrained and instilled that part of one’s worth is to be found in one’s physical appearance, I want you to know that your worth is not found in the hair on your head or even the freckles on your face. Your worth is found in the way you make other people smile and in the light that you bring to this world simply just by being in it.

And yes, yes your hair will grow back as you heal. And you will heal. And healing will be a roller coaster of emotions with both mental and physical twists and turns, but the bravest thing you can do along the ride is to embrace who you are inside at every step of the way.

The bravest thing you can ever do is choose to accept yourself every time you feel as though you can’t.

Advocating with Crohn’s

Life has a funny way of working out. It certainly doesn’t feel that way when you are diagnosed with a condition like Crohn’s disease, or going through a flare, when there seems to be very little to look forward to… but things can and do change.

Twelve years ago, I could never have imagined that I would be doing what I am doing right now. I was devastated when I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at the age of 14, which on top of my existing juvenile arthritis diagnosis, felt like another hurdle that I may not be able to overcome. Fast forward to 2020, and my outlook on life is very different, with those awful and challenging experiences fuelling everything that I do.

We’ve all heard the age-old advice of spending your time doing something you love. Growing up, I never realised that this would happen through patient advocacy – but it did. Even going back to the early 2010s, I had never heard of the term ‘patient advocacy’, and I had certainly not met any other advocates doing what I, and so many others now do. When I discovered it, there was no stopping me.

“If you do what you love, you’ll never work a day in your life.”

My patient advocacy journey began in 2012, when I was invited to become the first young person’s representative on a national clinical studies group for arthritis and other rheumatological conditions in the United Kingdom (UK). The invitation came from my former paediatric rheumatologist, who I met while attending a young person’s ‘meet and greet’ event at the hospital. At this point, I had been under the care of adults for around 12 months, so this was an opportunity for us to meet other young people in adults, while also being able to chat to those still under the care of the paediatric team. It’s hard to believe that this was only the second time that I had been in the presence of other young people with arthritis – the other time being in 2010, at the age of 16, when the hospital held an information day for young people. I had gone through the majority of my childhood without meeting another young person with arthritis or Crohn’s disease. It’s hard to believe it, but in the days when social media hadn’t really taken off (but when MSN Messenger was a thing), it was pretty difficult to be able to have a conversation with somebody else who ‘understood’. Having been presented with this new opportunity to help embed the voice of young people in research, I jumped at the opportunity to get involved.

I attended my first meeting in December 2012 in Manchester, down the road from where I live and where I was studying. I didn’t know what to expect, other than I had over 50 pages of material to digest ahead of the meeting. Thankfully, I was able to meet an experienced parent who was in a similar role to me on the group, but instead representing the patient and not-for-profit organisation voice. She was a huge source of help, inspiration and reassurance when I was sat in a room with over twenty of the most experienced, talented and ‘famous’ healthcare professionals and researchers in paediatric rheumatology from across the UK. While they were all lovely and made me very welcome, I found the experience totally overwhelming. I struggled to ‘understand’ what my role was, and I really didn’t appreciate the value of my experience, thoughts and ideas – which are the very insights needed to make research and care better for other people, like me.

As the years passed by, I met more and more researchers, healthcare professionals, and other individuals, who invited me to join different meetings, projects and activities. I was genuinely excited by the opportunities presented, and the realisation that I could help to make a meaningful difference because of my experience of living with chronic conditions since childhood. Looking back, this phase of my life was the one where I felt I ‘moved’ to that final phase of accepting my conditions, looking beyond the limitations and realising my value. It’s where I evolved into a strong, able and confident advocate for myself, and others, in every possible situation.

The majority of my patient advocacy was and continues to be within the world of rheumatology. I feel as though I have an allegiance with rheumatology – it’s where it all began, and I’ve come full circle if you wish! I also expanded my reach to chronic, long-term conditions more broadly, particularly focussing on the voice of children and young people, with a variety of different organisations and projects. The one area I felt I would like to ‘do more’ in was in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). This began with contributing to different articles and news pieces about IBD, before I branched out to a few different opportunities where I have been able to share my experience and help shape research and other activities for the community. One example was as part of an Immunology global community advisory board for a pharmaceutical company wanting to make a positive change to how they engage and involve the patient community. More recently, another new avenue identified was the CCYAN 2020 fellowship, which has been a wonderful experience.

People often ask ‘how’ I get involved in such advocacy work, and the answer is always because of ‘connections’. People I have met – either at conferences, other meetings, through fellow patient advocates, through healthcare professionals, and through social media, believe it or not. Getting yourself known is really important, and there are so many ways to do that. Platforms like WEGO Health (https://www.wegohealth.com/), Savvy Cooperative (https://www.savvy.coop) and of course CCYAN and the Health Advocacy Summit (https://www.healthadvocacysummit.org) are fantastic places to start, regardless of ‘where’ you are on your advocacy journey. The beauty of advocacy is that you can do as much or as little as you want. For some, advocacy is not for them – and that’s absolutely fine. For others, like me, advocacy is a part of daily life, where you quite literally live and breathe it – which is incredible. There really is no right or wrong. If you want to help and change things, then you should. There are plenty of people and organisations out there who can help you on your way too. You have your advocacy veterans, you have your advocacy newbies, and everyone in-between – each with a wealth of information, experience and talents to share. I can guarantee you that you will learn something from everyone you meet – I know I have, and that is often the best part of the job… meeting new people, constantly learning, and forging lifelong friendships, often out of pain and heartache. There’s something particularly beautiful and poignant about that.

As I look back, on what has now been eight years in patient advocacy, I feel incredibly blessed to have had the opportunities that I have had. It certainly hasn’t been ‘easy’, especially on top of living with chronic conditions, studying, caring for relatives, and also trying to enjoy some downtime – but it has all been worth it. For every person living with a condition who has felt less isolated… for every researcher who has changed the way they think because of something I have said… for every policy decision which has been informed by the insights I have shared… that is what matters. Everything else is a bonus. A very special, and emotional bonus came in 2019, when I was informed that I had been nominated, and selected as a finalist in the Shaw Trust Disability Power 100 2019 - the list of 100 of the UK’s most influential people with a disability or impairment. In October 2019, I was invited down to London for a reception at the House of Lords in Westminster for the launch of the publication, which was such an incredible honour. During the event, I was reminded of how fortunate I have been to be able to do what I do, when so many others are unable to do so – and that is exactly why I advocate. I advocate for those with no voice. I advocate for those who are trying to find their voice. I advocate for those who don’t have the strength or energy to fight right now. I advocate for those with a voice, to amplify and support it. Never, ever forget that your voice matters.

If I could give my younger, less experienced self some advice, here’s what I would say:

Your experience is invaluable. You have been through some difficult times, but you’ve made it. You have so much to give, and so much good to do in the world because of what you have been through.

Don’t be afraid of speaking up, speaking out, and challenging others. It takes some confidence to be able to articulate your thoughts and present them, especially when what you have to say goes against the norm. If you’re thinking and feeling it, the chances are that you aren’t alone. Be brave and get your message out there.

Embrace unknowns, challenges and critique. You aren’t expected to know everything. If you aren’t sure, say so, and then use that as an opportunity to learn and grow. If you are challenged about something that you say, it can feel as though it’s a personal attack, but in most cases, it’s not. It can feel disheartening to hear others disagree with what you think, and it can be upsetting if what you say is not embraced. Feel free to have your moment of anger, but then pick yourself up and move on – you’ve got this.

You don’t have to say yes to everything. Far too often, I have been a ‘yes’ person, succumbing to often unrealistic requests for me to contribute to different tasks. I’ve done this because I wanted to help and make a difference; however, it has sometimes impacted on my physical and mental health, as well as my time. You are able to say no and should exercise your rights to do so. The people you are working with should understand, and if they don’t, you may wish to re-evaluate whether they are the right people to be working with.

You won’t necessarily get on with everybody you meet. This is also another difficult one for me. I am a natural people pleaser, wanting to ‘get on’ with everyone. However, just like in reality, we aren’t compatible with every other human being – and that’s okay! There may be those where relations are kept purely professional, while friendships may be forged with other advocates you meet That’s part of life. Don’t feel ashamed or worried if those feelings arise.

There is space in the advocacy world for you. If you see other patient advocates and organisations occupying the space and think that you shouldn’t be encroaching on their territory – then get those ideas out of your head! You are just as entitled to be involved as everybody else, and don’t let the minority stop you from showing up. You are likely to come across certain figures who may believe that they are the only ones who should be active as patient advocates, but trust me, they’re in the wrong. The whole ethos of patient advocacy is to promote and protect the interests of patients and their families. As far as I am concerned, the more advocates we have, the better! Position yourself within communities who stand together to lift each other up. That’s where you want to be!

Crohn’s in College: Perspectives from a Former D1 Student Athlete

By Rachael Whittemore

Erin and I met in a serendipitous way - I was flaring and having a rough day at work, so I had to switch places with someone at work so I could sit instead of running around in surgical dermatology. She had come in for a triage appointment. We were talking and I made a joke about my stomach and she replied - “oh, I totally understand that, I have Crohn’s.” It couldn’t have been more perfect. We laughed about our IBD and bonded over our love for UNC. I also found out she would be starting a job at the clinic soon! She became a part of our “PA pod” and a beautiful friendship began. Erin is someone who gives her all in everything and is a light to anyone she meets. Like everyone with IBD, her story is unique and she has found a way to truly thrive in spite of it. She graciously offered to answer some questions about life and her journey with Crohn’s disease.

We both share a love for missions and travel!

Tell us a little bit about yourself. What are you up to right now and what plans do you have planned for the next year?

Raised on a farm in rural North Carolina, I graduated from my dream university (UNC-Chapel Hill) back in 2017 and have stayed in this lovely city ever since. After graduating, I traveled some and then landed this sweet medical assistant job where I became Rachael’s trainee. I am still gaining experience hours in the clinic, with plans to apply to Physician Assistant programs next summer. Along with working full-time, I have been pursuing a second degree in Public Health from North Carolina Central University. My hope is to join public health education and community outreach into the way I practice as a Physician Assistant one day.

Working as MAs together at Central Dermatology.

What was it like being in college and starting to experience IBD symptoms during a time that is often deemed “some of the best memories you will make?” How was this affected by you playing a sport?

Overall, my first year of college was pretty miserable. As a first year student athlete, having my first true flare within the first month of training was about the worst timing it could’ve been. I had experienced some fatigue and abdominal pain throughout my senior year of high school but, with the stress of starting college courses and the physical toll softball was taking on my body, the pain and exhaustion was consuming. I had no idea what was going on with my body and why it seemed to be betraying me. I couldn’t perform athletically the way I had before and no one believed me when I tried to explain how I was feeling. In their defense, I didn’t know how to advocate for myself since I didn’t understand what was happening. Nevertheless, I still felt isolated from my teammates, coaches and friends. It looked like I was some freshman who came in lazy, poorly prepared physically, and mentally weak. In reality though, I was struggling to get out of bed in the mornings for weights. I slept on any bench I could find in between class (even if it was for only 5 minutes). My body constantly ached and I’d be back in the weightroom or on the field before I ever felt any recovery from the last training. I’d clutch my stomach at night from the pain. The majority of the time, I felt awful physically and, in turn, felt awful about feeling so weak and letting my team down. It was a difficult time for me.

How long did it take for you to get an official diagnosis? Was it difficult? Did you have any issues with providers not taking you seriously?

From my first symptoms back in high school to the beginning of sophomore year at UNC, it took over two years and five different doctors to diagnose my Crohn’s disease. This journey was definitely one riddled with frustration and hopelessness at first. I knew my body felt off but after having three different doctors tell me things like, “It’s just a stomach ache, suck it up,” and “Well, if your primary care provider doesn’t think it’s anything, I don’t either,” I decided that I must be crazy and I just had to deal with the pain. When the flare hit me hard at UNC, I went to another doctor to reevaluate for a fourth opinion. After a lot of advocating, he finally tested some labs through blood work. The results showed that I had severe iron-deficiency anemia but the cause wasn’t looked into any further. I remember offering up that maybe it was related to the significant, recurring abdominal pain I’d been experiencing but that was quickly brushed off. My diet was adjusted to help increase my iron intake, but I felt worse as the diet consisted of all the foods that (I now know) cause my flares. It wasn’t until after I had to medically retire from the softball team at the end of my freshman year that I went to see my fifth and final provider. She sat with me, listened to me, and fought with me to find an answer. Within about a month or so, I finally had my diagnosis. The diagnosis proved to others that my struggle was real, but more importantly, it finally gave me a chance at finding some peace.

What advice would you give other young adults with IBD who may have been seriously playing sports prior to their diagnosis?

I would love to encourage my fellow IBD athletes that this diagnosis doesn’t have to mean an end to your athletic career. I was blessed in that, by my senior year, my Crohn’s was in remission. I laced up my cleats and wore that Carolina jersey proudly for a final season. Was my experience the same as my teammates? No, my conditioning had modifications and some days I had to listen to my body and rest. But who cares? There’s no shame in that. In fact, it’s even more incredible that we’ve been provided the opportunity to compete and perform at that level despite our adversities. I found immeasurably more joy in my sport that final season and realized how much I had taken it for granted before. No matter how much we pour ourselves into our sports, we are not entitled to perfect batting average, fielding percentage, or even health. Sometimes, we get to be creative and find ways to integrate back into our sport or even just an active lifestyle. If you are able to continue athletics, I highly recommend having an honest conversation with your coaches and teammates about expectations and trust. Don’t be afraid to advocate for yourself and your health. If you aren’t able to continue your athletic career, I grieve with you and that loss. I understand the identity crisis that ensues as soon as you are no longer an athlete, however, so much growth comes out of this season of life. I encourage you to shift your hope into something greater than a sport.

What advice do you have for young adults who are trying to find their way after their diagnosis?

First, I’d recommend taking some time to wrestle with the reality of the diagnosis and what this means for you personally. Lean hard into your community because having a support system is so crucial. It can be overwhelming in the beginning but trust me that things even out over time and you’ll start to adjust to your new normal. Once you get your bearings and start looking forward, don’t allow your IBD to define or limit you. There is so much more to you than your diagnosis. In a really twisted way, Crohn’s was potentially the best thing that could’ve happened to me. It caused me to really evaluate my life and my heart. It opened up my eyes to new passions and the desire to pursue them.

After medically retiring from softball for my sophomore and junior year, I was able to study abroad in Scotland for a semester and backpack around Europe for eight weeks after. I became more involved with a campus sports ministry called Athletes In Action, making lifelong friends and growing deeper into my relationship with God. I began to merge my loves of traveling and Jesus together on mission trips abroad. I’ve even recently been on a medical mission trip back in February, which was especially memorable for me. My heart has never been so full. All of this is to say, there is so much life left to explore and experience in this world. It would be a shame to let IBD take that away from you.

On a recent mission trip in Belize - working as a dental assistant!

What advantages do you think living with Crohn’s disease gives you in the real world? Has any reflection changed your perspective on living with a chronic illness going forward?

My Crohn’s disease has given me a certain confidence and purpose for my career path. Before all of this, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to pursue professionally and now I am passionate about becoming a medical provider one day. Even as a medical assistant now, I have been able to relate to my patients on a deeper level when reviewing biologic injections and other medications. Being able to sit with a patient and provide information and counseling from personal experience really helps build trust. While my experience with the healthcare system wasn’t a positive one to start, I’ve since had providers that have made me feel heard and valued. I want to be able to care for others in such a personal and profound way like my medical team has for me. Even if you don’t want to go into the medical field, there are lessons from our experiences on how to treat others that apply to all aspects of life.

I am also grateful for the advantages of endurance and perseverance that I’ve gained. With IBD being a chronic disease and after seven years since my diagnosis, there have been a lot of opportunities to wallow in self-pity. Don’t get me wrong - sometimes there are still days where I’m frustrated with having Crohn’s - but overall there have been so many victories over it. Each time I’ve adjusted my treatment regimen, found yummy recipes in my diet or shared my testimony, I've experienced joy. Celebrate the little things and appreciate the magnitude of what we’ve overcome. Living a full and purposeful life with IBD is possible and I want to empower you to continue persevering to find that. Throughout this experience, I’ve been shaped into the woman I am today and it has provided me the capability to handle all that will come in the future.

One Who Suffers

By Nikhil Jayswal

Disclaimer: The views presented in this article are entirely my own.

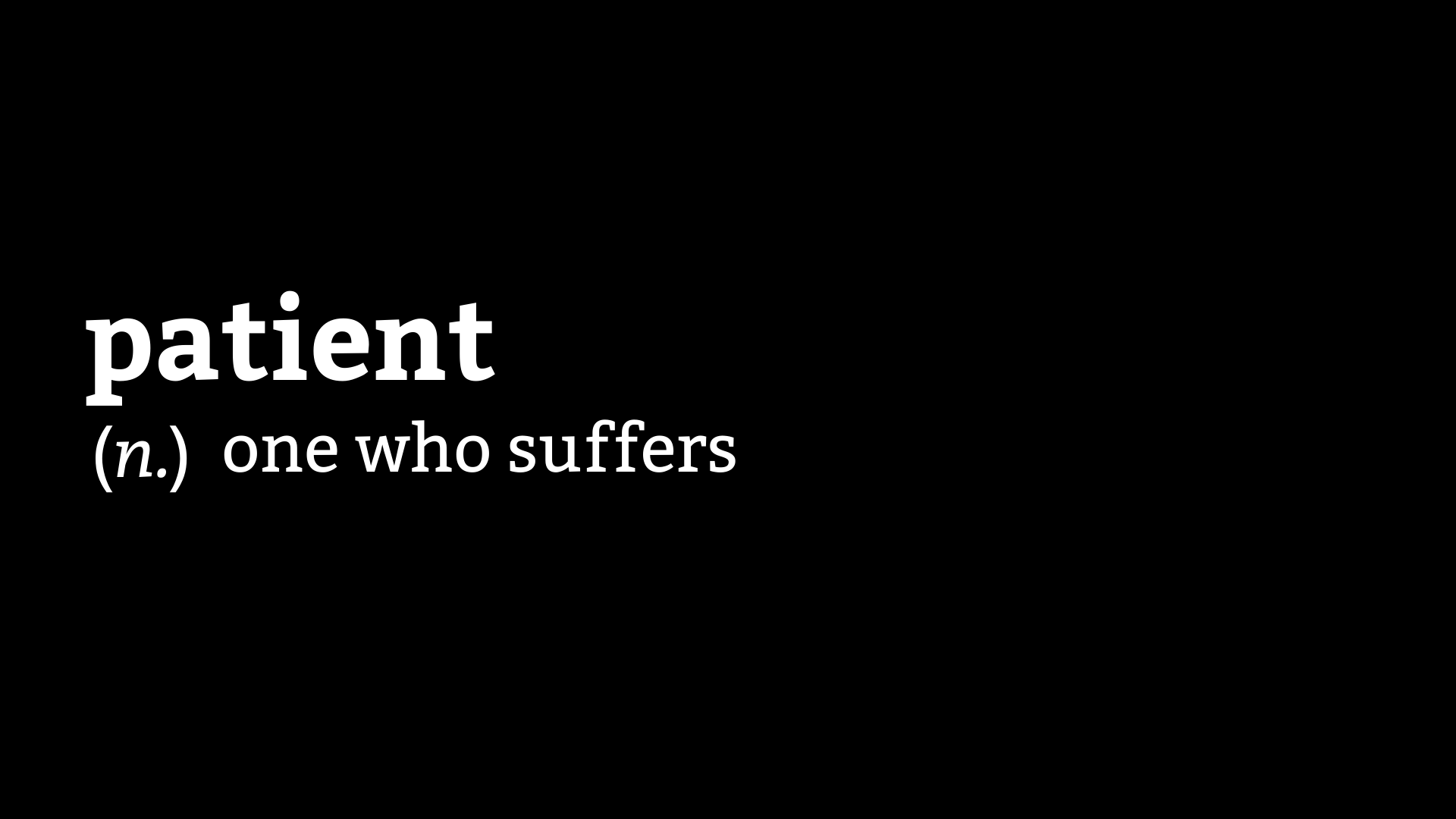

A couple of years ago, I stumbled upon the original definition of a patient - “one who suffers”. The word comes from the Latin word patiens, which is the present participle of the deponent verb, patior, which means “I am suffering.”

This definition, for some reason, is stuck in my mind, and I can’t help but ponder over it in many different ways whenever I come across it. Everything that I have ever experienced while navigating the healthcare system, makes me realize that I’m a patient because I’m patient. My virtue is now my label. The very characteristic that can garner someone praise is now a label for an ill person. To me, this contrast feels poetic, ironic, and cruel, all at the same time.

I tend to be very patient unless I’m in pain. I never knew though, that my patience, in essence, is my capacity for suffering. My patience has often been tested to the limits, by the healthcare system in my country. I can understand that the public healthcare system is not equipped to handle the volume of patients that it receives, which leads to delays and substandard care, but the private healthcare system has not been very kind to me either. The private healthcare system unfairly treats patients with weaker socio-economic backgrounds and highly favors the affluent ones. People with affluence and influence rarely respect any rules and often indulge in corrupt, immoral, and unethical practices to hijack the system and get the treatment that they want. This has often caused me much pain. I have struggled to find a hospital bed or a doctor on time, and I have been treated badly by the system because of my inability to afford the treatment I needed to stay alive.

It seems almost futile to me, to speak of these issues, because of a lack of support and the fact that people have accepted these issues. Breaking the rules to deny someone else the care that they might need more urgently is not a matter of concern for most people. In such an environment, only two kinds of people survive - the affluent or the patient. The word “patient”, hence, should be reserved for those who ultimately pay the price of a broken system, being abused further by egocentric people. This system has often made me and my mother weep as we struggled and oftentimes, begged for aid. Be it drugs, insurance, hospital admissions, diagnostics, or appointments, the entire ecosystem feels like one huge paywall.

People struggling with similar conditions are competing against one another to get care. Instead of standing together as a community, we are competing with each other, and the game is of patience. How early can you come to queue up at the OPD (outpatient department) window? How many hours are you willing to wait to see the doctor? However, the ones who win are those who do not play this game and the only thing you can do as you watch them get ahead of you is feel sorry for yourself and be ... patient.

Every time I write a part of my story, I relive a lot of trauma, caused not only by my illness but also by the healthcare system. Aiming to be an advocate amidst such an environment seems to be a foolish undertaking. In this system, money, power, and influence are advocates. I was incredibly lucky to survive. There are some who are trying to do their jobs as rightly as possible in this atmosphere, and it is these people, to whom I owe my life.

Privilege and patience have an inverse relationship. The more privilege you have, the less is the patience you can get away with. I have the privilege of education. I have the privilege of being able to obtain and absorb information on my own. I have the privilege of graduating from one of the best institutes in India. Without all these privileges, I would not be where I am today. These privileges though, are not of much use if you are not a person of importance, or a person of wealth, and are suffering from a severe form of some chronic illness.

These days I stare a lot out of my house to see people taking a walk, some with their pets, kids playing on the street, etc. When I look at them, I feel the same hollowness in my heart that I felt a few years ago, when I looked out of the hospital windows, at the outside world. My home feels like a prison to me now. I cannot step out of my house because people are not wearing masks, even after the fact that three COVID cases have been detected in the neighborhood. The lockdown may be over for other people, but it continues for me. The reason is simple. Even though wearing a mask and social distancing rules are not laws, breaking these rules to deny someone else (in this case, the vulnerable population) the simple pleasure of walking outdoors is not a matter of concern for most people. They’re not patients. I am. I haven’t been able to follow-up with my doctor in six months. I’m buying my ostomy supplies at higher rates than usual. Why? Because I’m a patient, and thus it is my destiny to suffer. Thankfully, I am not in a flare, but many of my friends are, and they are unable to step outside to buy medicines. Why? Because they’re patients too.

Now anytime, someone tells me that I’m a patient man, the irony and cruelty of it dawns upon me. This word often rings and echoes around in my head, and it has been doing so much more these days as I feel trapped and helpless, and at the mercy of the non-patient population. Advocacy, currently in India, has many different dimensions, that are neither pretty nor easy. Similar to the ecosystem that thrives on the patience of the under-privileged, we need an ecosystem of advocates, working in different ways, that can help the actual patients get the care they require and deserve without having to suffer as much as they do currently.

Until that happens, for me, and others like me, even though dictionaries define a patient differently now, the experience of being one still echoes, very loudly, the original definition - “one who suffers”.

Relaxing with Crohn’s

By Simon Stones

R&R… rest and relaxation – a concept I have long struggled to grasp, but one which I have learned to embrace, and enjoy over the last few months while being in lockdown.

Life in lockdown, because of COVID-19, has been a new and uncomfortable experience for many. Though for many people, like me, who have experienced isolation because of ill health, there has been a sense of familiarisation with what it’s like to be in isolation. Having your freedom taken away from you… being told what you can and cannot do… feeling cut-off from friends and family… worrying that your life is at risk. These are all experiences which so many with chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can understand, though in 2020, the wider population have had a glimpse of what that life is like, and how unpleasant and distressing it can be.

Having been unable to do so much because of ill health during my lifetime, it will come as no surprise that if I am well and able to do something, I certainly will do – even if I have to suffer the day after, because I overdid it on a ‘good’ day. I’m pretty sure that most people with chronic conditions have been there! We are told to overcome this pattern of activity by ‘pacing’. To some degree, I try to pace my life, but in reality, it’s not so easy! When you’re feeling unwell, you rest… when you’re feeling better, you try to cram as much in as possible. Life is so busy, and it’s difficult, especially after periods when you had no choice but to feel disengaged from the world, to not want to squeeze in as much as possible. After all, with conditions like IBD, you never quite know when the next flare up may happen. I have been entirely guilty of this – and hold my hands up! Over the last few years, my health has generally been okay. I have daily struggles, and have to manage pain, fatigue and other limitations, but I am generally able to function. This has meant that I’ve been working full time on my PhD, working part-time in a freelance capacity and volunteering tens and tens of hours per week, on top of caring for my late mum, housework and socialising. It’s safe to say that I was driving through life at 100 miles per hour, not necessarily realising the impact of trying to squeeze everything in.

I started to re-prioritise commitments in 2019 as I started to care for mum on a full-time basis during what would be her final few months. While caring for mum full-time, I was still trying to balance a full-time PhD, part-time freelance work, and volunteering – mostly because I didn’t want to let people down, and also because I struggled to say ‘no’. I decided enough was enough in July 2019, when I found myself sat up working in the middle of the night, every night. I felt totally drained. Despite loving what I do, there was no time needed to decide on my number one priority – mum. I suspended my PhD and stepped away temporarily from some voluntary work, keeping some freelance work ongoing to help me pay the bills. Sadly, mum passed away in November 2019, and I didn’t return to my PhD until February 2020, just as COVID-19 escalated. That’s when I really was forced to slow down. All of the conferences, meetings and events in my diary were cancelled, and from March 23rd, the United Kingdom went into ‘lockdown’. I was initially on the ‘shielding’ list and was told not to leave the house for a minimum of 12 weeks. As time went on, guidance from the British Society of Gastroenterology downgraded my level of risk to ‘high risk’, given that I was on biologics but not experiencing a flare, so technically I didn’t need to shield, but should try to do so where possible… which I did.

“Slow down and enjoy every day. Life goes by way too fast.”

I decided that I would be staying at home, full stop. It was the right decision for my own health, my dad’s health (who lives with me), and others in the community. The hardest part of course was not seeing family and friends, but we’ve all been in the same boat.

However, it was during the weeks and months that followed that I really slowed down. Surprisingly, lockdown enabled me to prioritise myself – something which I seldom do. I was now able to do things, just for me, without feeling guilty. It prompted me to stop, think, and remember that it’s not always a good idea to burn yourself out! During lockdown, I have learned to change my pace of life, and I have found surprising benefits on my physical and mental health. It has been nice to be more flexible each day. Don’t get me wrong, I do like to have some structure to the day, otherwise it’s very easy to get nothing done. However, it’s nice to be able to more or less shape my day around what I want to do. Although I have been working on writing up my PhD and doing other pieces of work, I have made more time for myself. Here’s a little flavour of some of those activities…

Yoga

I took up yoga a couple of years ago, but I never kept it up… until lockdown. Admittedly, my activity levels decreased quite a bit during lockdown, especially during the start when I didn’t even go outside for a walk. I felt as though I was seizing up, and so I decided to pick up from where I left off with yoga. I had the mat and the rest of the gear at home, so all I needed was an app. I came across the ‘Down Dog’ app, which was offering free access to all of its content during lockdown. I decided that I would try to do yoga for at least three mornings each week, though I found myself doing it every morning! It quickly became a way for me to ease myself into the day, stretch and loosen up my aching body, focus on my breathing, and ‘be’ here in the present. If you haven’t tried yoga, then I would seriously recommend it; though you may prefer pilates, or something completely different. The most important point is to find something you enjoy and have a go. I’ve noticed the benefits on both my physical and mental well-being, especially over time.

Gardening

I never thought that gardening would be on my list of hobbies that I would enjoy, but there we have it – you can even surprise yourself! We’ve had some beautiful weather during lockdown, and I was fed up of my lacklustre garden, so off I went to transform it! The fences and sheds have been painted, the lawns have been cut, borders and edges have been added, and there are flowers left, right and centre! What a difference. There’s definitely a sense of pride when you see a transformation happen before your eyes – especially one which you have influenced. It was also just a joy to be outdoors, in the fresh air, after being cooked up inside the house. I found it relaxing to be amongst nature – as well as topping up my vitamin D!

Getting outdoors

Once I felt it was safe to do so, I took myself to one of my favourite places, just 15 minutes away from where I live. The views are spectacular over my hometown of Bolton, Manchester and beyond. It’s all so quiet and peaceful – which is just what you need amidst the chaos and misery felt during this horrendous crisis. I realise that I’m incredibly lucky to live in a beautiful part of the country like this – something which others don’t have, though I hope others can find a little haven – whether that be the garden, a local park, or balcony.

Getting crafty

I used to love arts and crafts as a child, so taking this up again was nostalgic, and resurfaced lots of lovely memories of times spent with mum. My favourite card shop closed during the lockdown, so I decided to make my own! I dug out my craft box of ‘bits and bobs’, searched for some ideas online, and had a go at making a few different cards. As you can see, they were simple but effective (or at least I thought so!) I also really enjoyed just doing something, which required my focus and attention, but distracted me completely for everything else going on around me. After all, isn’t that the whole point!?

Totally chilling out

I’m not going to make out that I’ve been super productive throughout lockdown, because I really haven’t! For the first time in ages, I’ve read for pleasure – instead of reading textbooks and research articles. I’ve also gone through lots of films and TV programmes – who doesn’t love a good box set? Having total chill out days, or ‘duvet days’ as I like to call them, are the perfect tonic when you don’t have the impetus to do anything productive.

Sometimes, it takes certain situations to make us re-think the way in which we live, and I know the last twelve months have certainly prompted that for me. I am looking forward to spending time with loved ones, and eventually getting back to doing what I love to do, when it is safe and sensible to do so; but until then, I will carry on as I am doing. I will, however, be trying to continue a slower, more paced way of life, making sure it is filled with the people, experiences and opportunities that I love the most. I hope you can do the same too.

How to Support Your Friends with IBD

By Amy Weider

Growing up with Crohn’s Disease you tend to miss a lot of the action: birthday parties, hanging out with friends, and even going to school. It was either I was sick or stuck at another pediatric GI appointment that was 2 hours from my house. And to be honest, for most of my childhood I didn't really have friends. Because of my Crohns, anxiety, and depression, all of which were connected, maintaining friendships was not something I could do. The beginning of high school was just as rough and I lost a lot of friends over my unhealthy coping mechanisms for my depression and, while painful, it taught me a lot. Around my junior year of high school I got the help I needed and my Crohns began to go into remission. I was able to find friends and learn just what it means to have them. I have always been a bit of a weirdo and to find a solid pack of reliable folks that embraced me for my unapologetic behavior and I theirs was a lot more important than I had realized. My now chosen family (LGBTQ way of saying best friends) from college met me when my Crohns was very stable and I had to explain my disease to them. From this, I put together a few ways I found was a good way for them to show me their support and that made me feel their love and commitment.

1. Do your research!!

When a friend opens up to you about their experience it is smart to do a little more investigating to have a medical understanding of the disease. Read some CCYAN articles or follow content creators who have IBD. Also, allowing for space for your friends to open up about their experience with it and understand no two persons have the same lived experience or symptoms.

2. Be flexible

IBD can be VERY unpredictable so if you are one of those friends who shame folks for needing to cancel plans or change them (or shame folks in general) reconsider why you do this! A friend’s health, mental or physical, should be your first priority! Be flexible and allow for change.

3. Think about where the group is going to eat before hand

Simple things like this can really make a difference in a friends restaurant experience a lot easier. Ask your friends their dietary restrictions and do not assume that someone who has IBD also has dietary restrictions. Dietary restrictions can really make folks feel like a burden so be transparent and pick a spot for everyone!

4. Support them on good and bad days

It can be rough some days and not pretty. If you haven’t heard from a friend with IBD in a while, reach out. Flares can cause a lack of energy but that does not mean we don’t still need love and community!

5. Make room for correction and connection

Learning about IBD can be complex and everyone with it has very different experiences so create room for feedback and empathy if you say something wrong or hurtful. Allow for a bonding experience when someone shares their experience with you and love them more for it! I genuinely love when people ask me about my IBD and that allows me to feel whole.

IBD in the time of COVID-19

By Rachael Whittemore

Since COVID-19 has preoccupied much of 2020 and is likely here to stay, we continue to try to do our part in mitigating its spread and keep ourselves healthy at the same time. Being part of a “high risk group” is scary, regardless of whether or not we are on immunosuppressant medication. We’re also trying to continue work, school or salvage some of our normal routine before social distancing and wearing masks in public became the new normal. I thought I would share part of my experience during the pandemic - back in April, in the midst of trying to do everything right, take care of myself, and be responsible, I found out that I’d had multiple exposures to someone who tested positive for COVID-19.

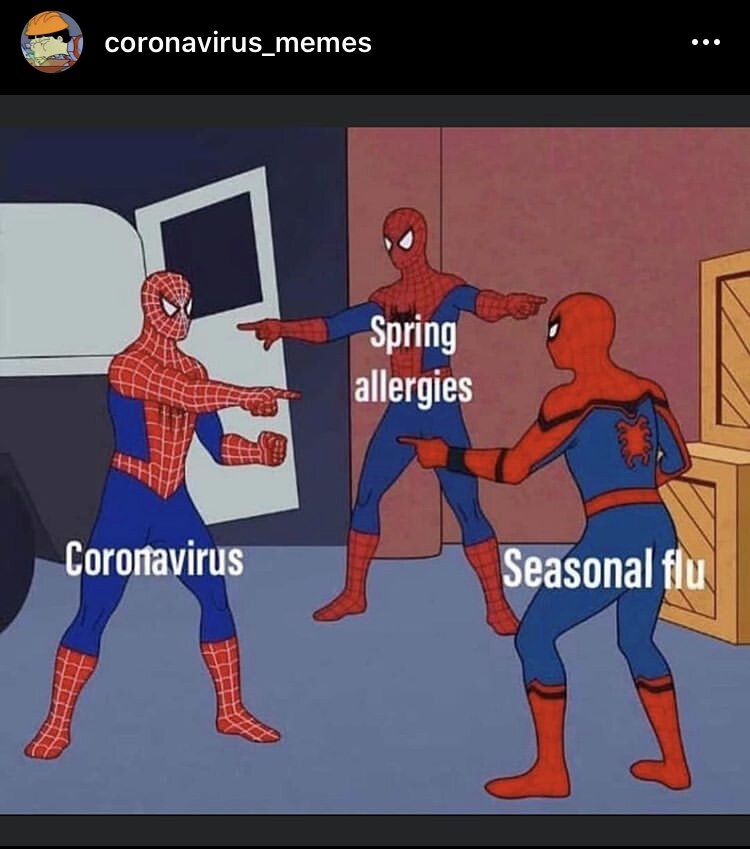

My heart sank a little bit and I became much more aware of the tiniest changes in how I felt. Was the tightness in my chest a sign of COVID-19 working its way into my lungs or just anxiety spiking? Was my terrible nasal congestion just worsening allergies with springtime in bloom or a sign of something more? You’ve probably seen plenty of funny memes circulating online that poke fun at moments when we need to sneeze or cough one time for something and then people within earshot of you give you death stares. They’re pretty funny, but when you know there’s a chance you could be infected or become infected, it hits you a little bit differently.

I was contacted by Virginia’s Department of Health and informed to stay where I was and self-isolate for 14 days. I had to take my temperature twice daily and record any symptoms on an online form. If I developed worrying symptoms, I had a number to call to determine if I qualified for testing. I was with my boyfriend, who had the same exposures I had, so it made me feel a little better; however, we were advised to largely avoid sharing spaces and each other as much as possible. It’s weird trying to keep distance from someone you’re staying with. What if your day has been rough and you just want a hug? In the time of COVID-19 isolation, you can’t do that. Being deprived of the comfort and connection we share with family members, friends and significant others is unsettling, especially for me. I’m a hugger, and I echo the sentiment that I won’t take another hug for granted once we get this thing under control.

So what did I do to prepare myself in case I got sick? I poured time into reading evidence-based resources about COVID-19. What we knew, what we didn’t. I was part of a Facebook group of medical providers from across the country that sought to share studies, experience, innovations and anecdotal evidence gained from treating COVID-19 patients. I looked at studies coming from elsewhere in the world about what treatments, if any, showed promise. A small part of me, thanks to my interests in medicine and public health, was wholly invested in how everything was unfolding. But most of me was trying to be as proactive as possible to keep my immune system up, avoid a flare and to stay above the rising waters of anxiety and dread in my mind.

I hydrated better than I had in weeks. I started taking a supplement with high dose Vitamin C and zinc every day in addition to my normal meds. I cooked (mostly) healthy meals and prioritized my diet and medication regimen so I could avoid any flares in case I got sick. I tried to prioritize sleep, but this was hard for me without my usual busy schedule and ability to run outside to have me feeling sleepy by the end of the day. I took Benadryl and, on my worst nights, one of my anti-anxiety medications that I usually save for days when I feel really out of control. Although I felt guilty about it, I tried to be gentle with myself and search for ways to set up a better sleep routine.

Fast forward a week: we were doing well and decided to go for a car ride since the weather was sunny and beautiful. We drove out on one my favorite country roads and marveled at the blossoming farms and apple orchards with the windows down. For some reason, I had started to feel nauseous and sweaty, sort of like when you might pass out. I don’t really get carsick, I thought. It didn’t smell the greatest since farmers were planting, but I usually didn’t react to bad smells either. We turned around, my boyfriend teasing me about being carsick but soon realizing I truly felt terrible. I laid down at home and hoped this “episode” would pass, yet I didn’t feel any better. For the next several days, I had waves of nausea, diarrhea, little appetite, dizzy episodes, chills, photophobia and some pretty intense migraine-type headaches. No to mention fatigue that prompted me to call for possible testing. I hadn’t had any fevers but knew something wasn’t right. My ulcerative colitis (UC) flares were never like this – I’d never had “dizzy spells” or felt so off. Even when my UC tired me out, I rarely would spend hours on the couch on a heating pad in one position, content to do nothing.

It was decided that I did need testing due to my symptoms and positive exposure. I felt lucky in this regard, because I know it hasn’t been easy for some in the US to get tested. Most are instructed to self-isolate and monitor symptoms and only seek treatment if they’re having trouble breathing. I also had had little to no respiratory symptoms. My nasal congestion had been worse, but I didn’t think much of it since my allergies were bad this time of year anyway. I had attributed some chest tightness to anxiety more than anything else. As I had been closely following developments at that time, I learned that COVID-19 could present with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of smell/taste, headaches, severe fatigue and other symptoms (1). Did I have COVID-19? It certainly seemed like a high possibility. My boyfriend, thankfully, was fine. I went to get tested at a drive-thru site nearby. After I got the not-so-fun, but necessary, long swab inserted into my nose and a sample taken from my nasopharynx, I was told to head home and to continue to self-isolate. I would have my results in 7-10 days.

How you get tested. Not fun!

A couple of days later, I finally had some appetite and felt like maybe it was a day I could get off the couch a little more. I got a call from my primary care provider: I was negative! I have to admit, I was relieved, surprised and also a little skeptical at the same time. As you may have heard, the testing methodology we have is not perfect and appears to have higher than desired false negative rates that can be attributed to various causes (1,2). RT-PCR (more about that here) may be the best widely-available testing we have, but many clinicians are relying on testing along with the clinical picture of the patient in front of them to determine how to proceed. Because of this, I acted like I had the virus, continuing to wear a mask once I completed quarantine and was allowed to go out (this was before mandatory masking inside was required in Virginia and North Carolina). I went out earlier or later, kept my distance from others and thoroughly washed my hands several times daily.

Thankfully, after 4 to 5 days, I finally started feeling like myself again. I felt like cooking and eating more than soup and applesauce. I wasn’t exhausted after taking a walk to the mailbox and back (with no one else around, of course). I still had some lingering loose stools for several days, but that finally improved too. I felt lucky that I didn’t flare on top of being sick, but made sure to be careful and ease back into my regular diet. I still worry about the possibility that my test could have been a false negative and I unknowingly infected someone else. Whatever I had, though, I made it through. Being sick during a global pandemic is hard. Trying to digest changing news and guidelines every week is hard. Hearing about exponentially rising cases and deaths is scary. Realizing that our world will never be the same after this is weird and scary.

Though I’ve been working through anxious thoughts during this time, I took time to slow down and be thankful. I wasn’t that sick. I had family and friends checking up on me. One of our friends brought us groceries. My boyfriend told me funny stories outside the bathroom while I was trying not to have diarrhea and throw up everywhere at the same time. I also was reminded to give my body time to heal. I’m used to being busy and balancing multiple things in my life at any given time. I have my normal life I’m used to living, even with the ups and downs of UC. I, like many others, probably don’t pause enough during the day to take a deep breath and remind myself of what I should truly be thankful for. If strict self-isolation has taught me one thing, it’s to stop and check in with yourself and on those you care about. While acknowledging that we are trying to navigate the storm that is a global pandemic, celebrate the little victories, even if you have to do it virtually.

IBD Resources in the time of COVID-19 - as always, discuss any questions with your GI provider*:

COVID-19 (Coronavirus): What IBD Patients Should Know

Coping with the stress and anxiety of coronavirus