NEWS

Energy Management with a Chronic Illness

By Varada Srivastava (India)

Finding a way to manage time with a chronic illness is a complicated process. It can be frustrating to figure out the new normal when you are originally diagnosed. For people with chronic illness it can be very difficult to figure out what is physically and emotionally possible for us to do that day. There are a few theories that have come to help us cope with this.

Moreover it’s very important for people who don’t have a chronic illness to understand it.

Christine Miserando is a lupus advocate who is known for coming up with the spoon theory. According to her, the difference between being sick and being healthy is having to make choices or to consciously think about things the rest of the world doesn’t. The healthy have the luxury to live life without having to make constant choices which is something most people take for granted. People with chronic illness are given a certain amount of spoons whereas healthy people have an unlimited supply. In her story, she gave her friend 12 spoons to get through the day. Each spoon represents the amount of energy we have for a certain task. For people with chronic illness, each task is also divided into smaller tasks.

For example: wearing clothes in the morning requires a series of decisions in which we have to keep our illness in the front of our mind. If you are getting blood drawn that day, you need to make sure to not wear long sleeves; if you feel the onset of body ache, you need to wear warmer clothes. These micro calculations take up the majority of our mental space. Do I take my medicine before or after lunch? Should I just wear a summer dress to relieve the pressure on my stomach? Are my hands too sore to handle buttons? I can't do many tasks if I take pain medicine. These are only a few of the many questions we tackle everyday. Each task requires a game plan. This constant mental gymnastics is incredibly tiring.

Emmeline Olsen wrote another article for IBD New Today which focused on the pitfalls of following the spoon theory. The spoon theory is based on the loss people with chronic illness face. But according to Emmeline, having a chronic illness piles stuff onto our original to do list. She gave the analogy of a filled bucket, healthy people can fill their bucket as much or as little as they want. Having a chronic illness is like filling the bucket with stones, each time you do a task which is exclusive to people with chronic illness, a stone is added to the bucket. Having a flare is compared to having a bucket filled to the rim. The worse the disease gets, the heavier the bucket is, the more chance it has of overflowing.

Having read both these theories, I think I tend to follow a mixture of both. Right now, I'm in remission, I am able to carry a heavier bucket. Doing daily tasks is comparatively easier and the stones in my bucket are less. However during a flare when I don't have enough energy to get out of bed the thought of lugging a bucket around seems exhausting. The amount of tasks seems overwhelming. That's when I like to follow the spoon theory. It helps in breaking down everyday tasks into smaller, more manageable activities.

Dealing with a chronic illness is very subjective, while some things work for one person they might not work for others. The goal is to find what works best for you, mostly through trial and error. And while going through this process it is very important to remember to be kind and patient with yourself.

Featured photo by Pixabay.

Keeping Up with Your Care

By Isabela Hernandez (Florida, U.S.A.)

Having a chronic condition isn’t easy. It’s something that needs constant upkeep, monitoring, and attentiveness. For me, a sometimes lazy 22-year-old college student, keeping up with my care is at times the last thing I want to do. I’ve neglected to refill my prescriptions, get my labs done, and reschedule my appointments. It is not something I am trying to recommend to anyone, but the difficultly of taking care of yourself is sometimes just plain irritating and difficult.

The way I’ve justified this behavior is: if I am going to have my ulcerative colitis forever, then I can take care of this later.

It creates this toxic cycle of neglect that can lead to dangerous outcomes. Once I let this neglect and annoyance take over, it’s difficult to pull myself out of it. Sometimes my wakeup call is even a mini flare. This would happen to me because I would view my disease as this burden that I could never escape. Something that only I had to constantly maintain day in and day out, and no one else. With this mentality, there was no way I was going to stay on top of my care. I would ignore things and push appointments off as much as possible. However, after my neglect facilitated the progression of an intense flare, I realized I needed to incorporate my disease into my life in a positive way.

What helped me the most was just treating my ulcerative colitis as a class that I needed to do assignments for and keep up with.

I started to schedule things into my day and treat it as task, rather than a pestering duty that if I didn’t do it, my health would suffer. Sometimes I would even write things into my planner so I could visually see that at this hour I absolutely needed to take my medication and at that hour I needed to call my physician for follow up labs. These were small changes that helped me stay as present as possible while trying to take care of my Ulcerative Colitis. It is something easier said than done but it is okay if you sometimes feel like taking care of yourself is too much and it is too hard. It’s because it is. It’s hard, its draining, and sometimes laziness takes over.

IBD patients are fundamentally built in a way that our health is the one thing always consuming our thoughts, and at some points this mentality overwhelms the mind.

And it is ok, too, at times get angry at our disease and wonder what life would be like without it, but this does no one any good. If you’re anything like me, finding ways to schedule health tasks into your day rather than just “getting around to it” really changed how I take care of myself. It relieved stressors that would follow if I didn’t do certain things for my care and allowed me to just do the task and move on. Just remember that even on days when we don’t feel like taking care of ourselves, we are still doing the best that we can do.

This article is sponsored by Trellus

Trellus envisions a world where every person with a chronic condition has hope and thrives. Their mission is to elevate the quality and delivery of expert-driven personalized care for people with chronic conditions by fostering resilience, cultivating learning, and connecting all partners in care.

The Impact Patient Advocacy has had on my Life

By Varada Srivastava (India)

“Patient advocacy has helped me feel a part of a community as well as cope with my illness.”

Patient advocacy is something I was first introduced to thanks to the blog of Natalie Hayden. She's a former news anchor and author of the blog, “Lights Camera Crohn’s”. A person who suffers from chronic illness has to constantly face challenges since the time of diagnosis, which is excruciating, to say the least. Overcoming challenges faced throughout our journey, from diagnosis to daily life, is something many of us experience. In fact, it seems like I would break down every time I read her blogs. I spent the entire day reading her blog and crying.

Many people don't realize the severe impact that chronic illness occupies in the lives of patients. How much chronic illness impacts our daily lives. Fighting an invisible illness is often isolating and heartbreaking. I discovered Natalie Hayden’s blog probably 5 years after my diagnosis and that was the first time I did not feel alone with my disease. I acknowledged the importance of patient advocacy when I realized that if I had this support when I was diagnosed, perhaps I would not have felt so lost until coming to terms with my illness.

India faces a lot of misdiagnoses because of health illiteracy, lack of medical facilities, and expensive medications. The feedback IBD patients may get is also typically insensitive.

Having a system of people who help you and encourage you during difficult times is crucial. It's easy to feel alone when you're struggling on the sidelines. And when people don't reach out, it can be difficult to stay optimistic. When it comes to Crohn's disease, it is often referred to as debilitating. And that it is. However, I’d also argue that what's really debilitating is constantly worrying about the unexpected.

It is common for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients to have what is known as "psychophysical vulnerability." 1 Stress, emotional distress, and inadequate coping skills can all have a negative impact on how the disease progresses and decreases quality of life. 1 There are always two types of reactions you receive from people. Friends who support us and people who give unwanted advice.

For several years following an initial diagnosis, the number of procedures and medications can be overwhelming. Determining trigger foods and finding medications that work, are also among the significant challenges. Having a network of individuals who have gone through the same process is helpful to a great extent. It has been an invaluable experience for me to connect with young adults from around the world who face similar challenges.

Patient advocacy has helped me feel a part of a community as well as cope with my illness. If you can find a friend who understands, even if you've never met in person, you can gain comfort. It may be something you didn't know you needed it until it was offered to you. I have accepted that rather than being afraid to reveal my disease, it is more helpful to be vocal about it and get advice on how to cope with it.

As a result of this, starting a support group at my university and applying for the Crohn’s and Colitis Young Adult Network fellowship has been two of the most rewarding personal experiences in my life. Being able to help others with things I have struggled with, is an incredible opportunity for me. I'm very grateful to patient advocates for this reason. The awareness of autoimmune disorders is constantly growing all over the world and I feel blessed to be a part of it.

Featured photo by Polina Kovaleva on Pexels.

Resource: (1) Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013; 144(1):36-49.

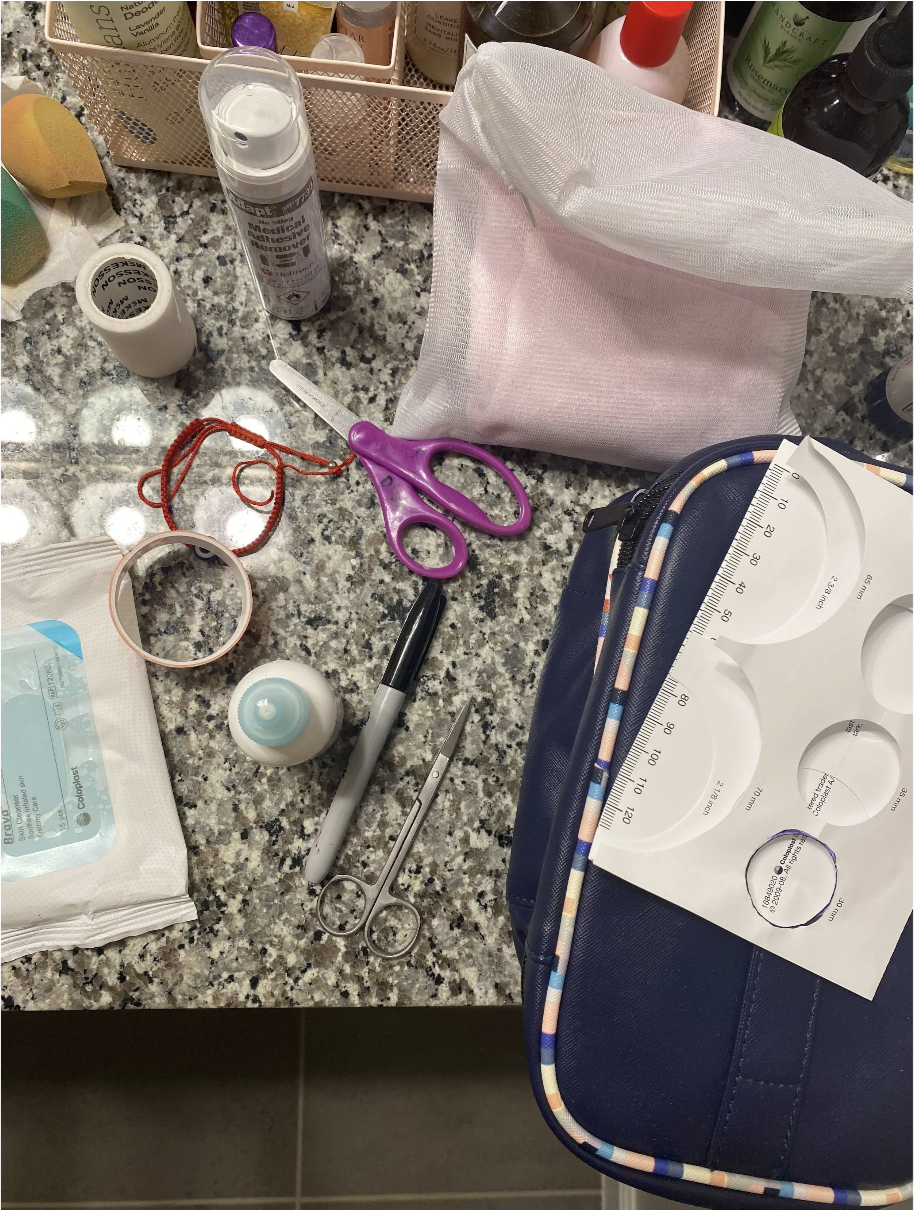

My Ileostomy Story

By Carina Diaz (Texas, U.S.A.)

In May of 2021, I went to the ER for what felt like the millionth time. I had been struggling with cysts and abscesses forming in my vagina for the past three years and this time was no different. Or so I thought.

I had already been to the ER earlier that week and was seen by a male doctor who, in hindsight, wanted to quickly drain the cyst and get it over with to move on to the next patient. I told him that I wanted a CT scan, but he said it wasn’t necessary. For my second ER trip of the week, I was seen by a female doctor. I made a comment about this being my eighteenth time having to do this in the last three years and with a look of concern on her face, she said, “That’s not normal. Let’s do a CT scan.” To which I said, “Brilliant idea.”

The part that I hate most about going to the emergency room is having to wait. And wait. A nurse takes your vitals. Then you have to wait. Someone comes to get your insurance information. More waiting. You tell the doctor what’s wrong. Even more waiting. The doctor comes back with a nurse. They do what they need to do. And you wait some more for either discharge paper work or to be admitted.

After getting a scan, it was decided that I would need incision and drainage surgery. But guess what? My gynecologist only does surgery at one hospital and it wasn’t the one I was currently at. So I had the joy of, you guessed it, waiting for an ambulance to come to transport me to another location. Watching the night sky through the back windows wouldn’t have been so bad if I wasn’t strapped to an uncomfortable bed made of plastic.

This was the second time I’ve had to get incision and drainage surgery, so it wasn’t a new experience to me. What was new was being presented the choice of potentially having to get ileostomy surgery. It would give my colon a break and let the fistula heal (a surprise that was discovered during the surgery).

To be honest, getting an ostomy bag was the worst-case scenario in my head as someone with Crohn’s Disease. It sounded scary and uncomfortable. What clothes could I wear? Would people see it? Would I smell? Am I going to wake up in pain after the surgery? When the hell will I be allowed to eat?! I don’t want a poop bag strapped to me. All of these thoughts were floating in my head while three doctors stood in front of me explaining the process. The good thing was that it would be temporary.

I let a doctor use a robot to cut me open and pull a bit of my intestine out. I didn’t wake up in pain, but I was scared to look at my body. The rest of the week was a blur of learning how to empty it, clean it, and how to live with this new change.

At the time of writing this, I’ve had an ostomy bag for ten months. While it has greatly improved my quality of life and lowered the severity of my symptoms, it has definitely been challenging. I have three different skin conditions, so my torso really hates having something taped to it. I have yet to find a bag that doesn’t irritate my skin. During my second month after surgery, I kept getting blowouts at night and barely got any sleep. It was painful and itchy. My ostomy nurse likes to describe me as “a real head scratcher.”

Having IBD makes me think a lot about the duality of life. I’m grateful that this surgery was an option for me because it has helped in many ways, but I still have to make sacrifices. I still have to deal with discomfort, and I’ve had to relearn my body yet again. That cycle will continue when I eventually (hopefully) get reversal surgery at some point.

Some people have positive experiences with ostomies and say that it has given them their life back. If that’s not the case for you and you’re also struggling with having an ostomy, try to remind yourself that you’re doing your best. Take it one day at a time and cry when you feel the tears forming. I recommend watching your favorite show if you’ve had a hard time changing your bag. Those stomas can be so unpredictable.

Constructing a Visual Language in the Chronic Illness Community

By Ibrahim Z. Konaté (U.S.A. and France)

Featured photo by JULIO NERY from Pexels

Learning at the age of 23 that I have a life-long disease was incredibly destabilizing. Once my care team developed a treatment plan that allowed me to regain some normalcy, I felt that I was still struggling to find my footing in this new reality.

The power of receiving my diagnosis lay in finally having the vocabulary to explain to others what I was experiencing, but I was still left without the tools to process this journey for myself.

I turned to my care team and was introduced to resilience, coping, acceptance, and many other important post-diagnosis concepts. Though I was able to receive guidance on these tools and worked to incorporate them into my life, I felt like I was missing something. As these words started piling up, it became harder for me to grasp their meaning.

The more I read about these words, the greater the chasm between myself and these concepts grew. I was meant to apply these ideas to my life but felt incapable of seeing them as anything beyond research frameworks.

I needed a way to animate these notions to see how I could fit them into my daily life. As a visually-oriented person, my first reaction was to see what imagery was already associated with these terms. When I put these words into Google Images, I was confronted with drawings of flowers growing through cracks in the sidewalk and stock photos of mountain hikes. Though these images got the basic point across, I was seeking something that could translate these ideas from words on a page to relatable human experiences and emotions.

For inspiration, I took a trip to the Brooklyn Museum and saw an exhibit entitled The Slipstream: Reflection, Resilience, and Resistance in the Art of Our Time. This collection showcases the work of intergenerational, BIPOC artists to “hold space for individuals to find their feelings of fear, grief, vulnerability, anger, isolation, and despair—as well as joy, determination, and love—reflected in art.” Though this exhibit was curated in response to the global pandemic and social events of 2020, I recognized my own struggles in the featured artwork. My favorite part of the exhibit was a room dedicated to centering pleasure to cope with and overcome conflict.

This is black text written on a white wall. At the top of the image is the word “Pleasure.” Below this image is a paragraph of text that reads: “In tumultuous times, experiences of joy, humor, leisure, and rest can hold radical possibilities for transformation. These artists capture moments of everyday pleasure, be they located in family, friendship, and community, in life’s daily rituals, or in creativity and the act of art-making itself.”

I started to wonder - if I could place any piece of art in this room to represent my experience as a Crohn’s Disease patient, what would I choose?

I spent the next week searching through digital archives to find an image that not only would embody my journey thus far but would also remind me of how developing resilience would help me keep moving forward. Finally, I found the perfect image, bought a poster of it, and hung it up on my wall. Now, the first thing that I see when I get up in the morning is a picture taken by Malian photographer, Malick Sidibé, entitled Nuit de Noël.

This photograph was taken in the early 1960s after the liberation of most West African countries from colonial rule. I think about the insecurity that was experienced by many people, including my parents, during this time of transition. When I see this picture, I remember how my family taught me that even in uncertainty one can still smile, dance, and hope that the future brings better days.

A square picture frame with black borders hangs on a white wall. The image in the frame is a black and white photograph showing a man and a woman dressed in light clothing dancing at night in a courtyard. Below the framed image are 5 sunflowers.

Words are important, but sometimes they are not enough. To conceptualize the abstract notions of resilience and acceptance, I needed to find imagery that could help me envision these concepts in my life. My belief is that there is something incredibly universal that can be found in our subjective experiences. I want us to create a new visual language to describe our journeys in this community. My hope is that we can replace the stock photos we find when we search for images related to resilience with artwork or even our own pictures. So I ask, what images describe your story?

This article is sponsored by IBDStrong.

IBD Strong is a volunteer grassroots organization that provides a community of hope, connection, inspiration and empowerment to children, teens and families living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. They believe that every individual diagnosed with IBD deserves hope and opportunities to thrive. IBD Strong’s mission is to inspire and empower individuals living with IBD to not let the disease define them.

Taking the Road Less Traveled

By Mara Shapiro (U.S.A.)

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

- Robert Frost

This Robert Frost poem has been long imprinted in my heart. It was one of my mom’s favorite poems. My mom passed away from aggressive breast cancer when I was 8 years old. Ever since, this poem has felt like a connection between my mom and me. For years I have turned to this poem when I have longed to feel her close. However, this poem has also become a roadmap for me in many ways, a guide for finding my way through life’s adversity (of which there has been plenty).

“Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.”

This famous excerpt from the poem hits home the most and is the part most up for interpretation by readers. Two roads diverged in a wood… and I took the one less traveled by… and that has made all the difference. In the context of my life with chronic illness, the two roads here are being healthy and being ill. As one with a chronic illness, we are on the road less traveled. I interpret this last line to mean that my chronic illness journey has impacted me so strongly, led to so much personal growth, made me the person I am today and that it has made all the difference. It is often through the journey and experiences that are less appealing and less traveled that we find out the most about ourselves. Adversity and our response to it are our biggest teachers. That has certainly been the case for me.

For me, this poem has allowed me to see the meaning and value my chronic illness, my journey on the road less traveled, has had on my life. That is not to say that there have been countless times where I wished I was on the road more traveled, the journey of a healthy person, but through acceptance and perspective, this poem helped me see that I am grateful for the path I am on (even though it was forced and not a choice I made because the path looked like it needed more wear, to use the words of Robert Frost).

The general theme of this poem implies having a choice in which road one gets to chose. In many situations in life that is the case. However, I never viewed this poem within that scope because the roads in my life have been characterized by frequent dead ends, U-turns, K-turns, and certainly a few lonesome, unpaved, rugged roads. While the interpretation of this poem falls naturally onto those who have faced some difficult choices in their life and had to later grapple if they had taken the right path, mine differs slightly and takes into account such forced early life adversity that a lot of us with chronic illness can relate to.

I want to thank Robert Frost for helping me see that while the path of being ill is not the path I would have chosen, it has certainly made all the difference in shaping who I am and who I was meant to become.

The poem has been popularly interpreted to mean a lot of different things about the power (or lack thereof) of choice and how to retrospectively make meaning out of said choices. However, I have always had a different interpretation of this poem, as did my mom. We think of the roads, not as choices where we had full agency but rather roads that life put us on anyway and most importantly, the CHOICE we all have in making the most out of whatever road we end up on. Losing a parent as a child certainly puts you on the road less traveled. Being diagnosed and living with multiple chronic medical conditions, especially through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood also puts you on the road less traveled. Where I look to Frost and think of choice is in the last line, “And that has made all the difference.” I have been on the road less traveled my whole life, and it has made all the difference. I would not be ME without my journey on the road less traveled. Despite the suffering, the grief, the pain of this road we’re on together as people with chronic illness, I would not change the person it has made me.

_

I’m curious to know your thoughts and interpretations of “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost. Post a comment here or reach out to me on Instagram @m.shappy, I’d love to hear from you!

Featured Photo by Mohan Reddy on Pexels.

This article is sponsored by Lyfebulb.

Lyfebulb is a patient empowerment platform, which centers around improving the lives of those impacted by chronic disease.

IBD & Travel: Ethopia

By Fasika Teferra, M.D. (Ethiopia)

As a healthcare provider and Crohn’s Disease patient, I can tell you that living with IBD in Ethiopia is not easy. Most medications are not so readily available and doctors don’t speak English as their primary language. I hope through this piece of article give you a glimpse of how it is like for an IBD patient in Ethiopia and some tips if you wish to travel to our amazing country that is well known for its 13 months of sunshine!

Most low- and middle-income countries do not have access to quality and affordable medicine and health care. This information is widely known. However, patients and doctors still try to close the gap of this scarce resource and healthcare disparity as much as they can. As an IBD patient, I have had to rely on just oral medications. Other types of medicine are not available yet for IBD in Ethiopia. Managing my Crohn’s through adjunct therapy such as diet and stress control has proven effective for me, personally. When I have to schedule my endoscopy/colonoscopy, I would have to take a few days off work, as bowel preparation takes up to three days. Although medicine and other supportive treatments are not available here, patients still are able to manage their diseases with what they have, and IBD patients also can come to Ethopia and go as they please.

As an IBD patient, I have had to rely on just oral medications. Other types of medicine are not available yet for IBD in Ethiopia.

As an IBD advocate, one thing I have noticed among the diaspora community is fear of travel to other countries. Although it is scary to travel to a new place where you don’t know how the health system works or know a place to turn to, if God forbid, you need to go to the emergency care, I am here to tell you that it is not as bad as it seems. From my personal experience, IBD patients have a better travel experience when they bring a medical summary from their primary doctor to Ethiopia. Should you need an emergency care, just by reading that paper, a GP or gastroenterologist is able to understand your condition. In addition, bringing your own medicine is always a good idea as it is not readily available. If I were to recommend one resource that has helped so many it would be IBD Passport. It has a global database of a lot of GIs, their centre and ways to contact them even before you depart. I know for a fact that I would travel much more comfortably if I knew where to go to if I needed anything.

From my personal experience, IBD patients have a better travel experience when they bring a medical summary from their primary doctor to Ethiopia. Should you need an emergency care, just by reading that paper, a GP or gastroenterologist is able to understand your condition.

Even though it is widely known most of the advance IBD treatments are not available everywhere, that should not be a reason to travel and explore new places. I am sure there are many tools out there that can give some perspective on your destination’s healthcare system but it is always a good idea to research ahead of travel. IBD should not hold you back from adventures!

The Unknown with IBD: My Journey of THE DIAGNOSIS

By Maalvika Bhuvansunder

Crohn's, is a term I am familiar with now, to the extent it feels that I am synonymous with it. In medical terms, Crohn's is defined as an inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, which manifests in symptoms such as abdominal pain, unexpected weight loss, and many more (Baumgart & Sandborn, 2012). However, all I could understand was that I am in for a journey filled with lots of pain.

It was in 2016, that my health started to get worse. I lost a lot of weight, was not able to eat properly, and was moody all the time. My family and I initially thought that maybe it was the flu or food poisoning. However, my health never seemed to improve. Deciding to go to the doctor, I had made up my mind to expect the worst. To my pleasant surprise, I was diagnosed with anaemia. I say pleasant because my mind had made up that I had cancer, and in comparison to cancer, anaemia was a piece of cake. Despite getting treated for anaemia, my health remained the same, with no improvement whatsoever. Later, I was diagnosed with amebiasis (Pritt & Clark, 2008). I was relieved thinking finally, I have a proper diagnosis. Things seemed to improve for a while; however, it started to get worse. At the suggestion of my GP, we met a gastroenterologist. Now, before this, I was completely unaware of such a discipline in medicine, so my family and I went in completely blank, not knowing what to expect.

“All I could understand was that I am in for a journey filled with lots of pain. ”

The first thing my gastro told me, based on my previous reports, was there seemed to be some sort of inflammation in my abdominal area. I was told to get a colonoscopy done, only after which the doctor could confirm a diagnosis.

On the way home, I started to research the entire colonoscopy procedure. I was stressed out reading the process and was hoping to find a way out of undergoing the procedure. Thinking back to it, I am not sure what I dreaded more, the prep process of having to drink that awful colon cleanse, or the actual colonoscopy itself. Had I known before what colonoscopy was, I might have been less skeptical about it. The day of the colonoscopy went pretty smoothly, and I was drowsy for most of the day. We were not told anything that day and had to return a few days later for the official diagnosis. We again went in completely blank, not knowing what to expect. That is when I got THE diagnosis, CROHN’S. Now, I had never heard such a term and neither had my parents. The doctor’s explanation regarding my treatment plan just sounded gibberish to me. The one thing that I could not take my mind off was, this condition does not have a cure; it will be with me for the duration of my entire life.

We always hear how an early diagnosis can solve half the problems; however, with any gastro-intestinal condition, the dilemma is that the symptoms are very similar, and getting an early diagnosis may not always be possible. From personal experience though, I feel with IBD it doesn't really matter when we get the diagnosis as it is not a curable illness.

“ This condition does not have a cure; it will be with me for the duration of my entire life. ”

The scariest part about IBD for me was the unknown. Not knowing when a symptom will hit you, how severe it will be, not knowing if you can make it to plans and outings, and not knowing if it's an IBD flare or the flu, always having to be afraid, fearing the unpredictable. I had never met anyone else with my condition, and I did not have anyone to ask questions about this. I was unable to comprehend why I got this and was really unsure about how I will get through it. Accepting this condition took me a long time. I realised something through this process, the importance of support. If we have the right kind of support and care team, slowly but steadily we will see improvements. Above all, we will be able to accept our condition, and it makes the predicament of the unknown a little less scary.

References:

Baumgart, D., & Sandborn, W. (2012). Crohn's disease. The Lancet, 380(9853), 1590-1605. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60026-9

Pritt, B., & Clark, C. (2008). Amebiasis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 83(10), 1154-1160. https://doi.org/10.4065/83.10.1154

Body Neutrality > Body Positivity

By Carina Diaz (Texas, U.S.A.)

My body has been through many shapes and sizes since the diagnosis of my Crohn’s disease in 2012. The combination of medications and inflammation has altered my weight, the shape of my face (thanks Prednisone), and effected my ability to exercise. After many years of weight fluctuations, I now see three people within myself: the person I picture in my mind, the one I see in the mirror, and the one I see in photos.

Halfway through 2017, I came back home from a four month internship in Florida in very bad shape. I had lost a lot of weight, had little appetite, was under constant fatigue, and went to the bathroom almost 20 times a day. I didn’t deal with many IBD symptoms in college outside of bloating and cramps, so this was new territory for me. I was bed bound for several years and shrunk down to skin and bone. I avoided my reflection every time I went to the bathroom. I felt like a shell of a person. My body felt like an itchy, uncomfortable sweater that I couldn’t take off.

“I still have days where I’m mad at my body, but being able to take a step back and shift my thoughts away from the frustration has brought back some peace.”

As my health slowly began to improve and my mind became more clear, I noticed how often my thoughts centered around the way I looked. I felt detached from my body and even more so after getting ileostomy surgery in May of 2021. I’ve had to relearn my body over and over again because of the constant changes IBD has put it through. It’s very easy to feel disconnected from your body when you have IBD. I’ve often felt that my body and I are two different entities at war with each other, and neither side wants to wave the white flag.

There’s so much content online about self-love and loving your body. “Start the day by looking in the mirror and say three things you like about yourself out loud.” “Love the skin you’re in.” “You’re beautiful just the way you are.” I’ve found that it’s not possible to feel good about yourself everyday. Our bodies change, even for people without health conditions. We’re constantly shown images of what we should aspire to look like and the products to buy to help us attain it.

A concept that has helped me reframe my thoughts around body image is body neutrality. It encourages you to accept your body for what it is and puts more emphasis on what you’re capable of instead of what you look like. To me, this means to meet my body in the day I’m in. For example, on days when I have low energy, I’m going to take care of myself by working from my bed, ordering takeout, having snacks and water within reach, and not worrying about the state of my apartment. I’m not going to expect myself to cook, clean, and run errands on a day that I’m not feeling well.

I know that this might not be a helpful concept to everyone, but it is a practice that has helped my mental health and self image. I still have days where I’m mad at my body, but being able to take a step back and shift my thoughts away from the frustration has brought back some peace. Instead of viewing IBD as a punishment from my body, I’m trying to remind myself that my body is going through this with me. Neither of us are to blame; it’s just our reality. We’re both doing the best we can.

RV Camping with Crohn’s: How I Reconnected With Nature After My Diagnosis

By Mara Shapiro (U.S.A.)

Featured photo by Nubia Navarro (nubikini) from Pexels.

“Look deeper into nature, and then you will understand everything better.”

I’ve always found nature to be healing, and where I’ve felt the most relaxed. Previous to my Crohn’s diagnosis I was a competitive rock climber and would frequently travel to some of the best outdoor rock climbing destinations in the United States with my climbing team. It wasn’t just the act of rock climbing or spending time with some of my closest friends, it was truly the beauty, peace, and serenity of nature that made me the happiest. I found a lot of my bliss in the mountains throughout my teenage years whether it was through rock climbing, snowboarding, or hiking.

A childhood dream of mine has been to own an RV so I could camp and enjoy nature with ease and virtually anywhere. This dream became a much more realistic goal when I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in July 2020. I was diagnosed at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota and I live in Southern California. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was safer for my dad and me to drive the two and half-day nearly 2000 mile trip rather than fly (we also got to bring my best friend and Corgi companion, Morty, on this road trip). I was pretty sick at the time and relied on diapers and lots of Imodium to get through that road trip, which we did a total of twice round trip that summer.

Every time we passed an RV or travel trailer of any kind I would point it out. We must have passed hundreds of them on the 2000 mile stretch of interstate. I would daydream about the day I would have my own RV and be able to just pull over and use my own private toilet whenever I needed it. Sitting in my Subaru Crosstrek wearing a diaper, you bet I was dreaming about all those RVers and how lucky they were to have their own toilet within arms reach. No more accidents, no more sketchy truck stop bathrooms… Of course, I dreamed of other parts of RV life too, and those daydreams helped me pass the time, a time that was full of such fear and unknown.

Fast forward to October 2021, I have graduated college, I have an amazing full-time remote job, and I am ready to start the process of finding and buying my own RV. After months of research, I decided on a Forest River R-Pod 190. It was a perfect size, weight, and floorplan for Morty (my 2.5-year-old Corgi and travel companion) and me. In small travel trailers like mine, the bathrooms are usually very small and called a “wet bath'' where the toilet and shower are in the same space and when you shower the entire bathroom gets wet. I was lucky enough to find a floorplan with a “dry bath”, where the toilet is fully separate from the shower! For the amount of time I spend on the toilet, I knew I needed a dry bath! Add this to the list of things that “normal” people with “normal” colons don’t think about…

At the end of November 2021, I picked up my R-Pod and camped in it for the first time! The past few months have been full of a lot of trial and error, endless learning, and many moments of frustration. I have also felt so empowered by my newfound confidence and independence. I have had so many new experiences and explored beautiful new places with Morty. I have fulfilled my childhood dream and created a new hobby and source of joy that has added so much to my life. IBD and chronic illness can take a lot from us, and can often make us feel out of control. For me, finding an accessible way to camp with my RV is one way that I have taken some of that control back.

Advice for Camping (or getting back into any hobby) with IBD

Take it slow!

I’ve learned (mostly by trying to do too much too quickly) that the best way to partake in strenuous activities is to do it slowly and at your own pace. It’s easy to look around at others and match their pace, but especially when it comes to setting up a campsite there is no rush and it’s not a race. So if I need to take a break and have a snack or drink or lay down on the bed in between setting up or taking down camp then I do! Find your pace and stick to it.

Ask for help!

Asking for help can be hard, but sometimes it’s so needed! Especially with camping, 9 times out of 10 your fellow campers are super friendly and always willing to lend a hand! As a solo female camper, I am hesitant to ask for help unless I really need it, but I have learned that there are usually kind people within an earshot who are there for you. Asking for help from friends and family to help you enjoy your hobbies is also key. Especially when flaring, I’ve been able to have my dad come to assist me with some of the strenuous camping tasks so that I could still enjoy some relaxing time in nature.

Acceptance is key!

Acceptance is a spectrum and some days and in some phases of life, acceptance comes easier than others. I have really channeled my inner acceptance narrative when I go out camping. I try my best to accept things as they are and as they come and not get too frustrated when something unexpected happens or I end up being more symptomatic than I had hoped. I could be feeling sick at home so I might as well be feeling sick in my camper in nature! “It is what it is, and I’m camping,” I say with a (forced) smile when the stress starts to build. Find your acceptance and get back to your beloved hobbies!

Whether it is camping or another outdoor adventure or trying a recipe you haven’t made since your diagnosis or trying something totally new that you’ve always wanted to try, I want to encourage you all to take that leap of faith, argue with that voice in your head that’s been holding you back, and go for it!

This article is sponsored by Lyfebulb.

Lyfebulb is a patient empowerment platform, which centers around improving the lives of those impacted by chronic disease.